Harbor Springs, Michigan, is a small town with a long and layered past. Long before it became a summer destination, this harbor was home to the Odawa people and later a crossroads for missionaries, traders, and settlers. Over time, a quiet village known as Little Traverse grew into a resort community shaped by steamships, Main Street commerce, and deep cultural traditions. The story of the history of Harbor Springs is one of continuity, where early roots and later growth exist side by side. This history helps explain why the town still looks, feels, and functions the way it does today.

Table of Contents

Video – History of Harbor Springs Michigan: 7 Powerful Stories Behind a Great Lakes Town

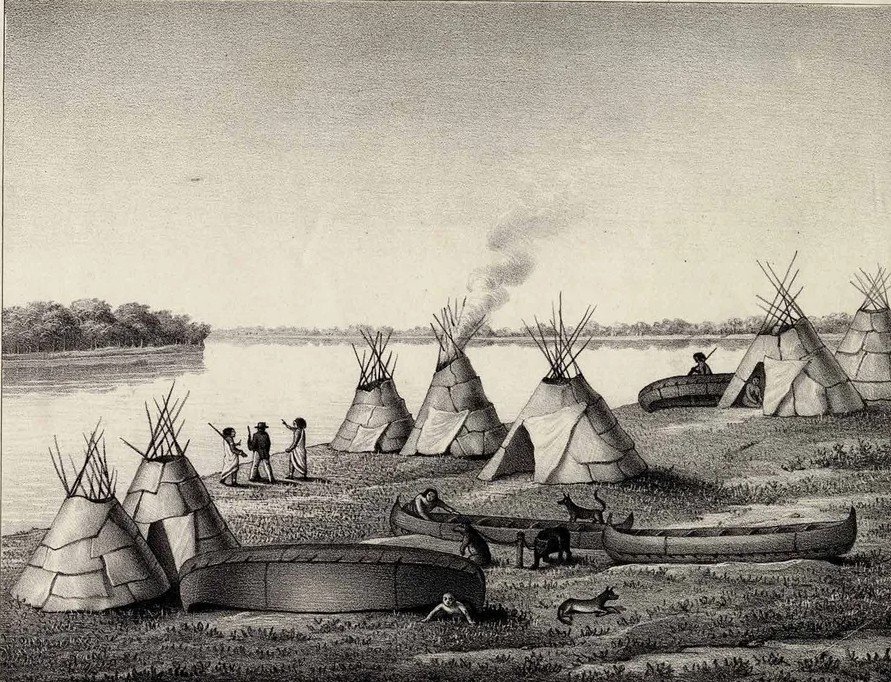

An Odawa Homeland Before a Town Existed

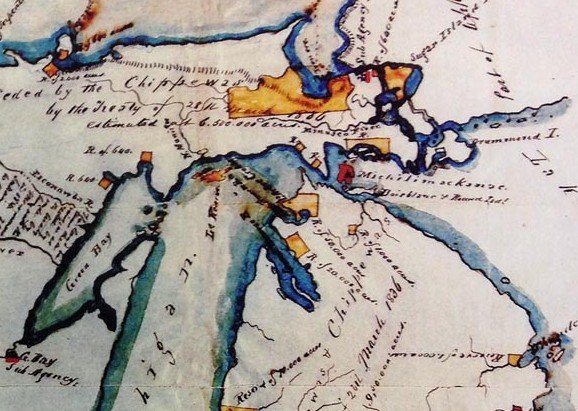

The history of Harbor Springs, Michigan, spans centuries, beginning long before the town had a name. The Odawa (Ottawa) people lived along Little Traverse Bay for generations, relying on fishing, farming, and maple sugaring. They called the area Waganikisi and returned seasonally to the bay’s sheltered waters. In 1691, French Jesuit missionaries arrived and named the region L’Arbre Croche, after a bent pine used as a landmark. This early presence shaped the cultural foundation of the town that followed.

From Little Traverse to Harbor Springs

By the mid-1800s, a small settlement known as Little Traverse took shape near the harbor. In 1858, the village was formally organized, drawing missionaries, traders, and settlers. One of the town’s earliest civic institutions was the post office. In 1869, Odawa leader Andrew J. Blackbird became postmaster, running the operation from his log home. Residents collected their mail in his kitchen, an unusual but meaningful chapter in local history.

Andrew J. Blackbird and Early Civic Life

In 1862, Little Traverse got its first official post office, and mail arrived by boat or horse trail. An Odawa leader, Andrew J. Blackbird, became postmaster in 1869, making him one of the few Native American postmasters in U.S. history. Blackbird even operated the post office out of his own log home – neighbors would stop into his kitchen to collect their mail. As an educated bilingual man, Blackbird worked tirelessly as an interpreter and advocate for his people. However, as the village grew into a resort town, pressure mounted to replace him. In 1877, amidst the changing social climate, Blackbird was removed from the postmaster role in favor of a white resident. It was a sign of the times, yet Blackbird’s legacy lives on: his house later became the Andrew J. Blackbird Museum, preserving Native artifacts and some of the original mailboxes from his tenure

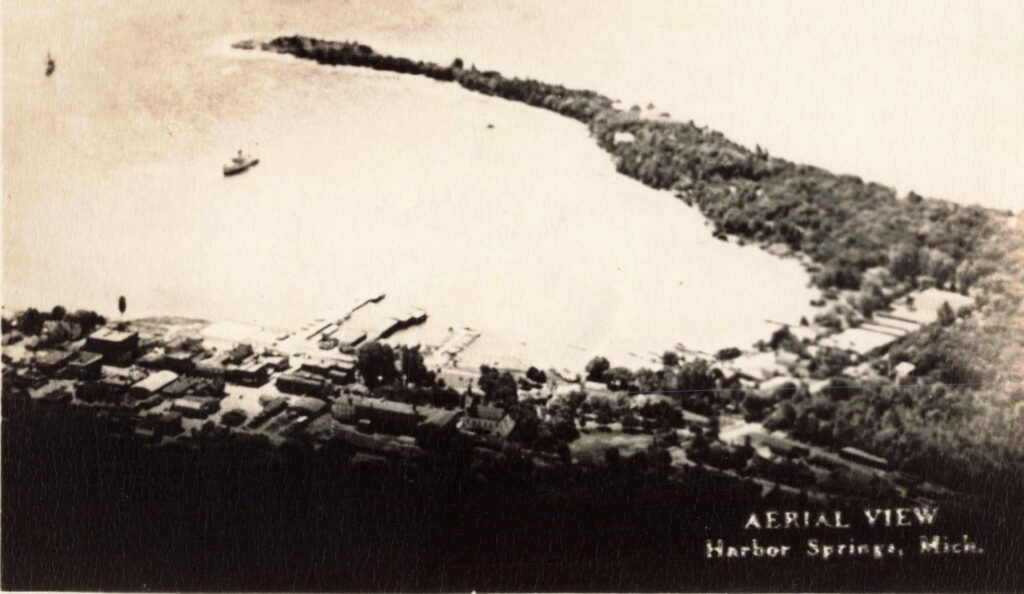

Incorporation and Growth in the Late 1800s

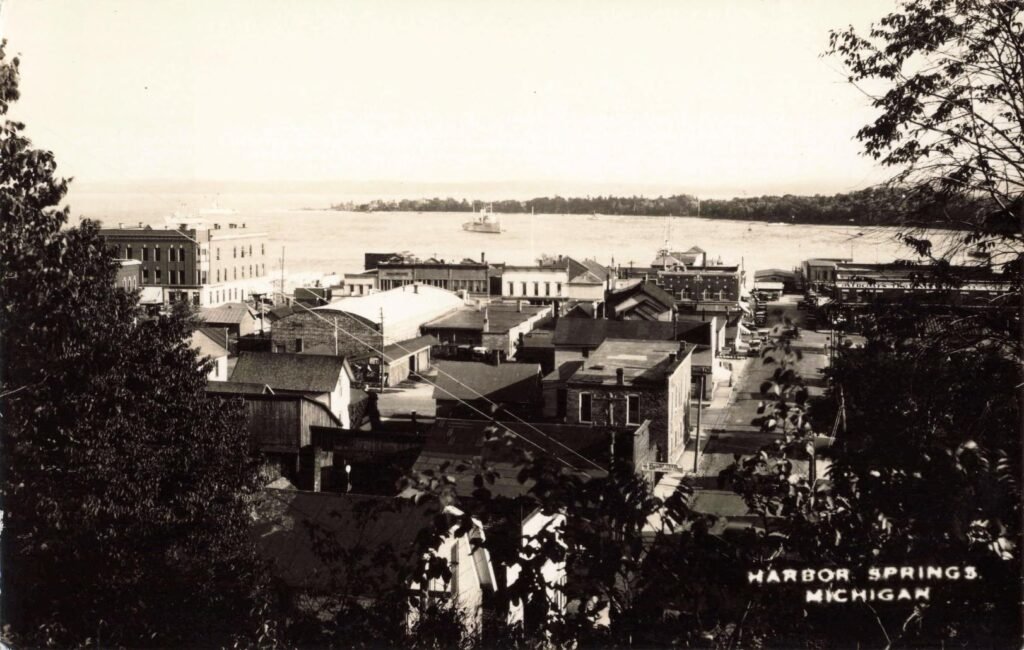

Harbor Springs officially incorporated as a village in 1880, taking on the name we know today. The History of Harbor Springs, Michigan, during the late 19th century is marked by rapid transformation. What had been primarily an Odawa community and a logging outpost quickly evolved as homesteaders, missionaries, and entrepreneurs arrived. The original Emmet County Courthouse was built here in 1886, a stately brick building atop a hill. (Harbor Springs was the county seat until 1902, when it moved to Petoskey.) Around the same time, rail service reached the area. In 1882, the Grand Rapids and Indiana Railroad extended north, making travel easier. Now tourists and settlers could reach Harbor Springs by train as well as by steamship, setting the stage for a resort boom.

Resort Culture Takes Hold

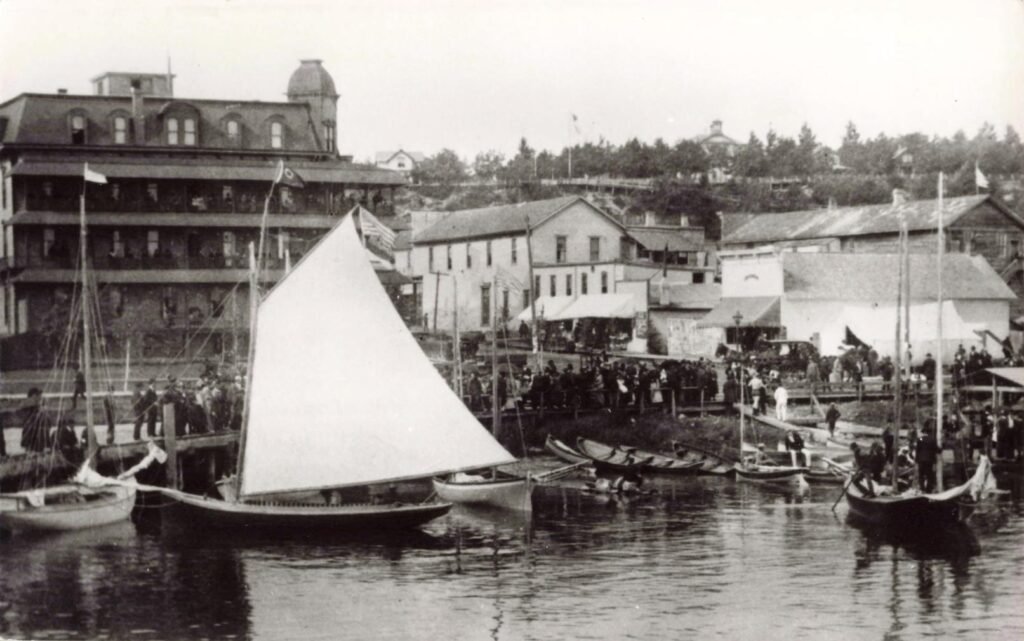

By the 1890s and early 1900s, Harbor Springs gained fame as a picturesque summer escape. Churches, civic groups, and wealthy families from the Midwest flocked to the cool bay shores. They established exclusive summer colonies like Harbor Point (a peninsula guarding the harbor) and Wequetonsing, where Victorian cottages and hotels sprang up.

The Emmet House, a modest hotel opened in 1876, was expanded and rebranded around 1900 as the New Emmet Hotel to cater to upscale visitors. It stood proudly on Bay Street near the docks, its broad verandas offering views of the harbor. In these years, the History of Harbor Springs, Michigan, became intertwined with leisure and luxury. By the 1920s, the town was nicknamed “Naples of the North”, boasting 11 hotels ready to serve the influx of summer guests. Vacationers escaped smoky cities for Harbor Springs’ fresh air, attracted by advertisements promising boating, bathing, and scenic beauty.

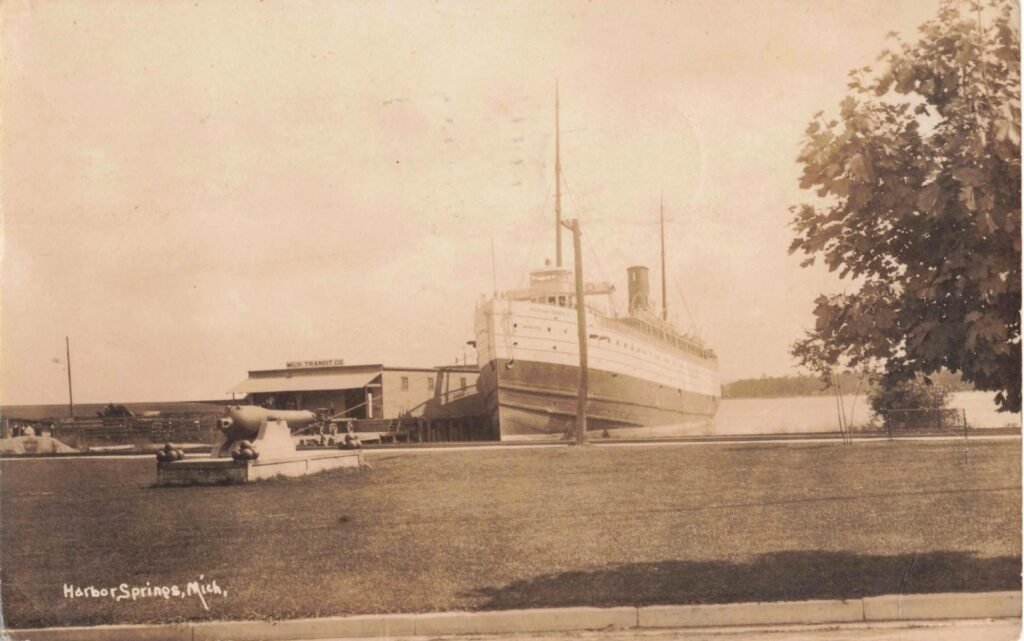

Steamships and the Busy Harbor

One hallmark of the resort era was the arrival of the great passenger steamships. Starting in the late 19th century, steamers from lines like the Detroit & Cleveland Navigation Company and later the Chicago, Duluth & Georgian Bay Transit Company made Harbor Springs a port-of-call. Towering white cruise ships – notably the sister ships North American and South American – became regular visitors by the 1910s and 1920s. They ferried hundreds of tourists at a time.

When a steamer docked at the municipal pier, the town would buzz with activity. Porters in uniform unloaded trunks and wicker suitcases, hotel omnibuses lined up to whisk arrivals to their lodging, and local youngsters sold newspapers or offered to carry bags. These grand vessels underscored Harbor Springs’ status as a premier resort destination on Little Traverse Bay

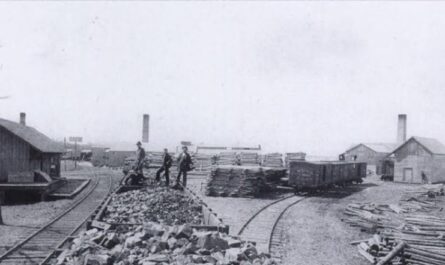

Working Waterfront and Local Industry

Meanwhile, Harbor Springs’ year-round community kept things running behind the scenes. The protected harbor wasn’t just for tourists – it supported a variety of lakeshore industries. Fishing was a mainstay; photographs from the 1900s show local fishermen with bountiful catches of trout and whitefish hauled from these waters. Lumber, the sector that had cleared much of northern Michigan’s forests in the 19th century, still had echoes here: Ephraim Shay’s Hemlock Central Railroad hauled logs to Harbor Springs until the timber played out.

A small boat-building business took root by the 1920s to craft and service the elegant wooden pleasure boats favored by wealthy vacationers. There was even a furniture factory nearby for a time, capitalizing on hardwood from the interior. Through these enterprises, locals found employment, and the history of Harbor Springs, Michigan, gained new chapters of entrepreneurship.

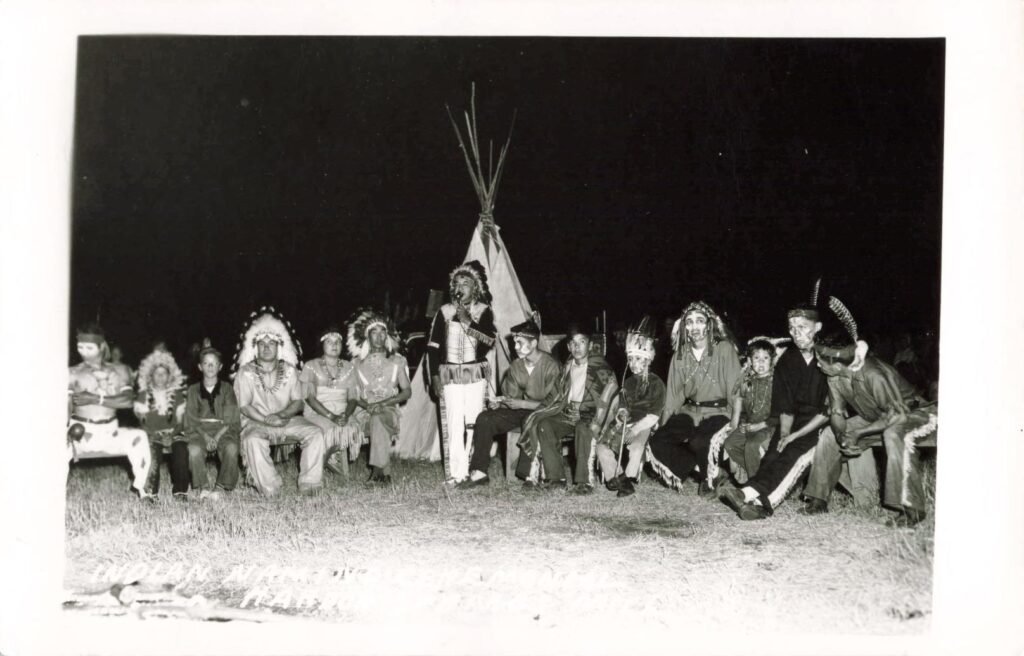

Odawa Traditions Continue in the 20th Century

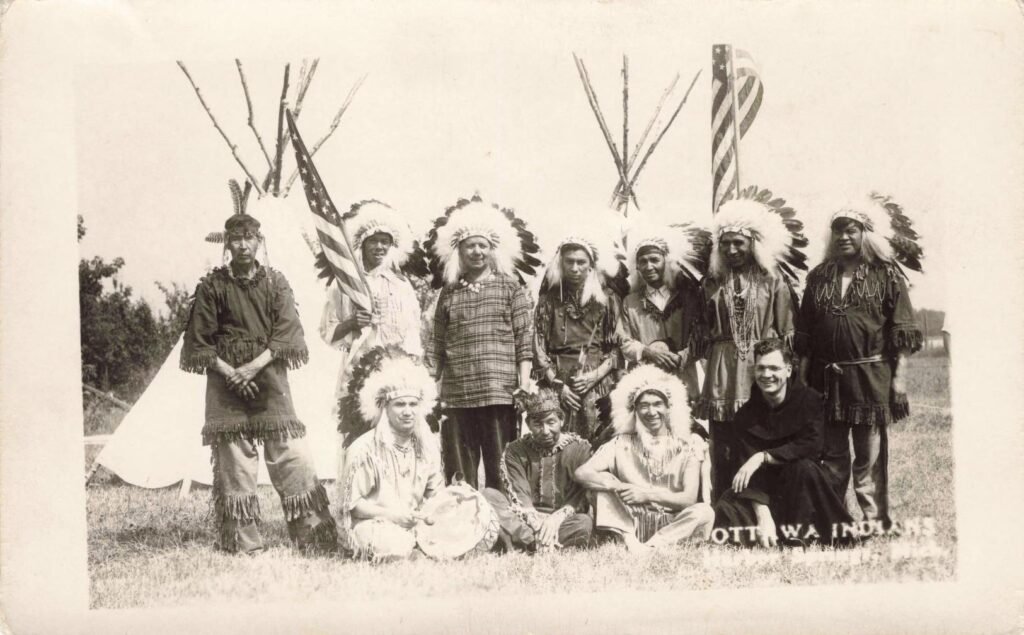

Crucially, the town never lost sight of its Native American heritage. Harbor Springs was and is part of the homeland of the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa. In the early 20th century, many Odawa families continued to live in town or in nearby communities like Good Hart and Cross Village. They maintained traditions such as powwows, storytelling, and crafts. Starting around 1912, Harbor Springs hosted an annual public event often called an “Indian Pageant” or Ottawa Dance, in which Odawa members performed traditional dances and ceremonies for the public.

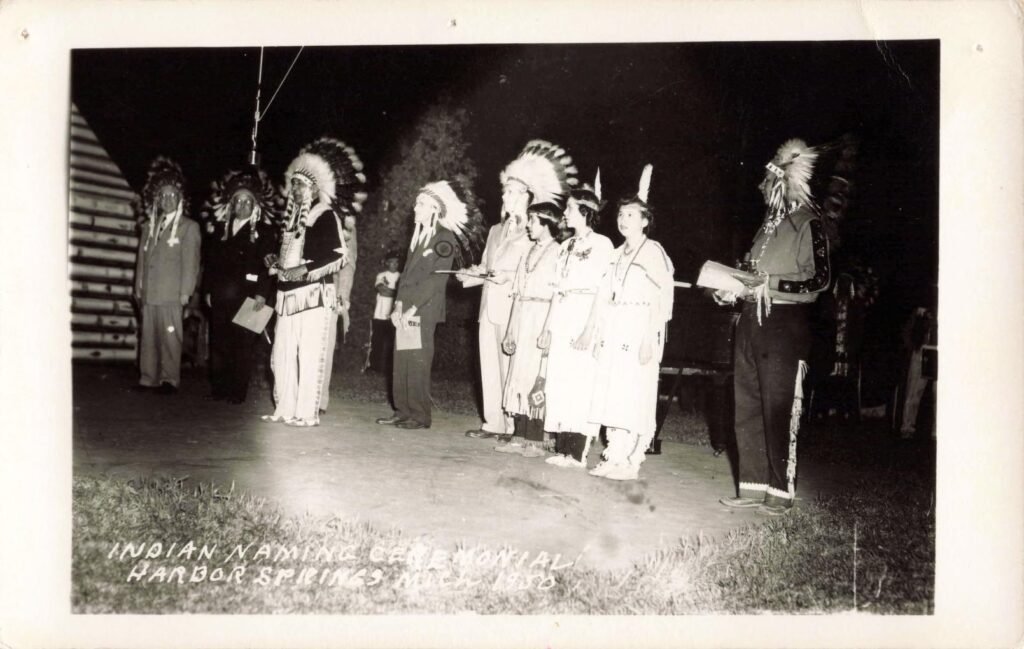

By 1935, a stone amphitheater called Ottawa Stadium had been constructed (later rebuilt in 1948) to showcase Ottawa Indian naming ceremonies and cultural demonstrations. These events, sponsored by groups like the Michigan Indian Foundation, were both a celebration of Odawa culture and a tourist attraction.

For example, each summer, an Ottawa naming ceremony would be held, where Odawa leaders bestowed Native names on community members – a solemn tradition made accessible to outsiders to foster understanding. During periods when Native customs were often suppressed elsewhere, Harbor Springs served as a relative haven where such cultural heritage could be openly celebrated. The very presence of these ceremonies into the 1950s speaks to the resilience and continuity of the Odawa community here.

Daily Life on Main Street

Daily life in the first half of the 20th century was a charming mix of work and play. Main Street remained the social spine of Harbor Springs. On summer mornings, locals would line up at the Post Office for mail and gossip. This brick post office building, opened around 1905, stood at the corner of Main and Spring Streets – a symbol of stability. Just down the block was the Harbor Springs Library, which had started as a one-room reading room in 1894 and grew into a two-story Carnegie-style library by 1908.

Children on their way to the beach would stop in to grab a book or say hello to the librarian. At noon, the church bells of Holy Childhood of Jesus (the historic Catholic church founded initially as a mission) would toll, and the scent of fresh bread wafted from Schmidt’s Bakery on State Street. In the afternoons, the scene shifted to the water – regattas and swimming lessons in July, fishermen mending nets, teenagers diving off the end of Zoll Street pier. Come evening, the glow of porch lights and the sound of crickets filled the warm air. Tourists and townsfolk alike loved to gather at the dockside park to watch the sunset over the bay, often serenaded by a local band or gramophone music from the Emmet Hotel’s lounge.

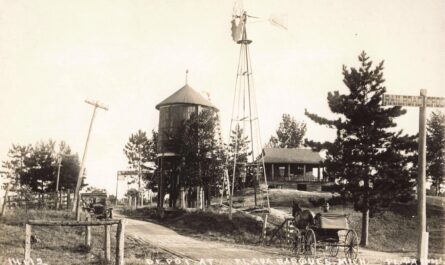

Ephraim Shay’s Lasting Impact

Harbor Springs also benefited from visionary residents who contributed to its progress. One was Ephraim Shay, the inventor of the Shay locomotive. After revolutionizing logging railroads in the 1880s, Shay settled in Harbor Springs and brought innovation to the town. He funded and installed a municipal waterworks system with miles of pipe, giving Harbor Springs one of the earliest running-water systems in northern Michigan.

Shay also had a whimsical, generous side. In the winter of 1895, noticing many local children had no sleds, he crafted hundreds of wooden sleds in his workshop and anonymously distributed them on Christmas Eve. The delighted children famously repaid him in pennies – each child bringing one penny – and presented Shay with a bouquet as thanks. Stories like this highlight how a sense of community and compassion runs through the history of Harbor Springs, Michigan.

Harbor Springs by Mid-Century

By 1950, Harbor Springs had gracefully grown up. The population was still small – around 1,200 year-round residents – but swelled many times over each summer. The town’s appearance had changed little in fifty years: many buildings from the late 1800s still lined Main Street, from the bank at one end to the City Hall at the other. This architectural continuity was not by accident.

Locals cherished their town’s historic character. Even as modern highways and car travel made the remote corners of Michigan more accessible, Harbor Springs held onto the slower pace of a bygone era. It remains true even today: walking down Main Street feels like stepping back in time, with authentic 19th-century storefronts and a picturesque waterfront that has looked nearly the same for generations.

Why Harbor Springs Still Matters

The history of Harbor Springs, Michigan, is visible in everyday life. Odawa traditions continue alongside century-old storefronts. The harbor still welcomes boats, though steamships are gone. Museums preserve early stories, but the town itself tells the larger one. Harbor Springs remains a place where history is part of the present.

Works Cited

- Andrew J. Blackbird Museum – Harbor Springs

https://www.cityofharborsprings.com/blackbirdmuseum - Harbor Springs History – City of Harbor Springs

https://www.cityofharborsprings.com/history - Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians – History

https://ltbbodawa-nsn.gov/history/ - Harbor Springs Area Historical Society

https://harborspringshistory.org - Great Lakes Passenger Steamships – Detroit & Cleveland Navigation Co.

https://detroithistorical.org/learn/encyclopedia-of-detroit/detroit-and-cleveland-navigation-company - Ephraim Shay and the Shay Locomotive

https://www.michigan.gov/mhc/museums/shay-locomotive