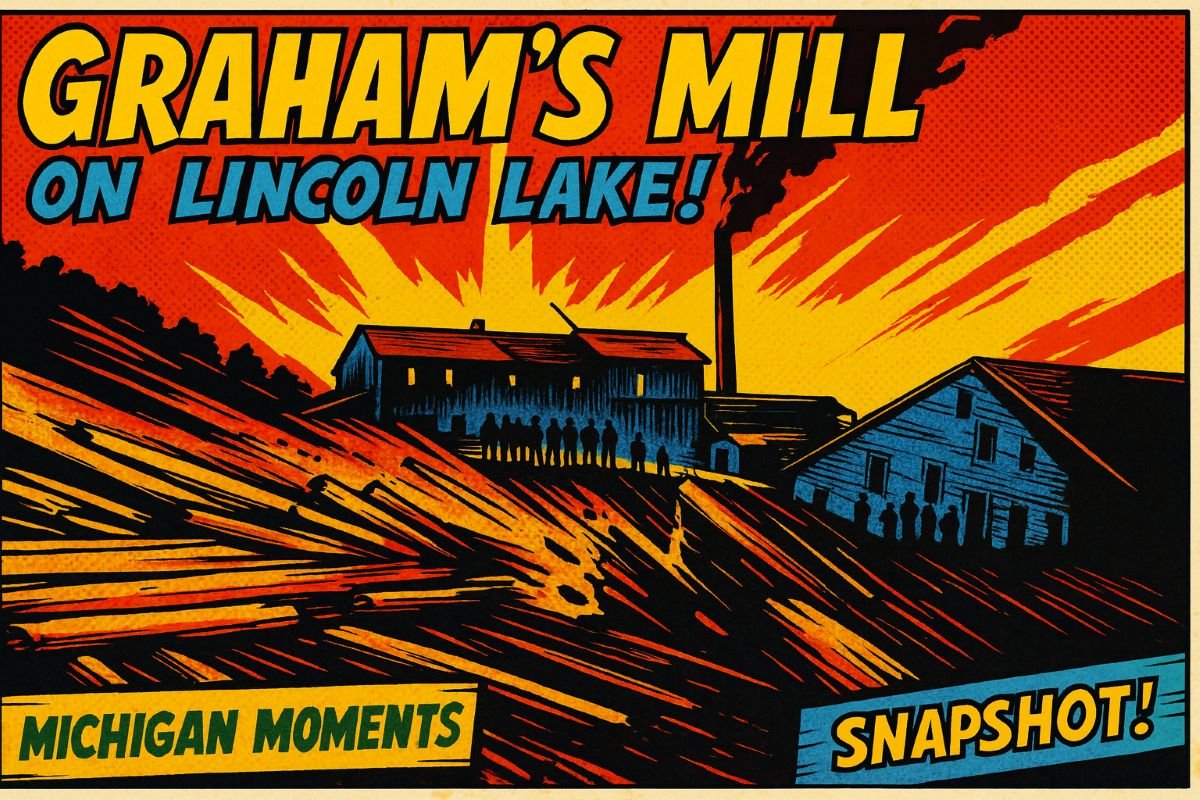

In a rare photograph dated 1885, a tall smokestack, rough frame buildings, and scattered timbers identify a hard-working lumber operation called Grahams Mill on Lincoln Lake in Mason County, Michigan. Handwriting on the print reads “Lincoln – now Epworth,” tying the scene to the small village that once stood just north of Ludington.

Grahams Mill on Lincoln Lake

A Busy Mill on Lincoln Lake

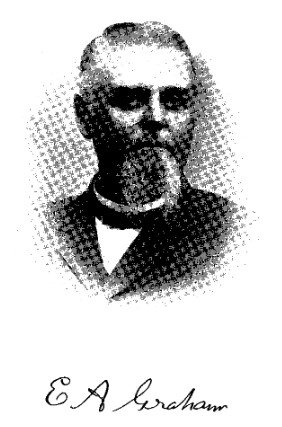

Research now shows that this complex was Graham’s Mill, owned by John Graham and operated by his son, Edmond Alfred Graham. The image captures the family business at its peak, with workers gathered near the mill and log piles lining the shore.

The Graham Family and the Lumber Trade

Graham’s Mill processed the white pine and hardwood stands that filled Mason County in the late 1800s. Logs arrived by river and by team, then moved through the saws to become boards for houses, docks, and businesses around Lake Michigan.

The Graham family’s interests did not stop at the mill yard. Edmond Alfred Graham became a prominent businessman in Berrien County. In 1870 he entered the steamboat trade, purchasing the steamer Union. By 1879 he had built the May Graham, a vessel that worked the St. Joseph River carrying freight and passengers between river towns.

Linking Mill Towns and River Ports

Because of Edmond Graham’s activities, this single photograph joins two corners of Michigan. On one side is Mason County’s lumber belt, where mills on the Pere Marquette, Big Sable, and Lincoln rivers cut millions of board-feet each year. On the other is Berrien County and the St. Joseph River, where Graham’s steamboats tied inland communities to the Lake Michigan harbor at St. Joseph.

Lumber from mills like Graham’s traveled by rail and vessel to build homes, grain elevators, and factories across the Midwest. The Graham family’s dual role in milling and shipping shows how closely these local economies were connected.

Lincoln Fades, Ludington Grows

When Lincoln was founded around 1851, it held enough promise that state lawmakers briefly designated it as the Mason County seat. The honor later shifted to Ludington, whose harbor and rail connections made it the region’s dominant port.

As timber stands thinned and the lumber boom cooled, smaller mill villages such as Lincoln lost population. Boarded-up structures and cutover hillsides replaced the earlier rush of activity. By the early 1900s, Lincoln had largely vanished as a civic center, kept alive mainly in photographs and family histories like that of the Grahams.

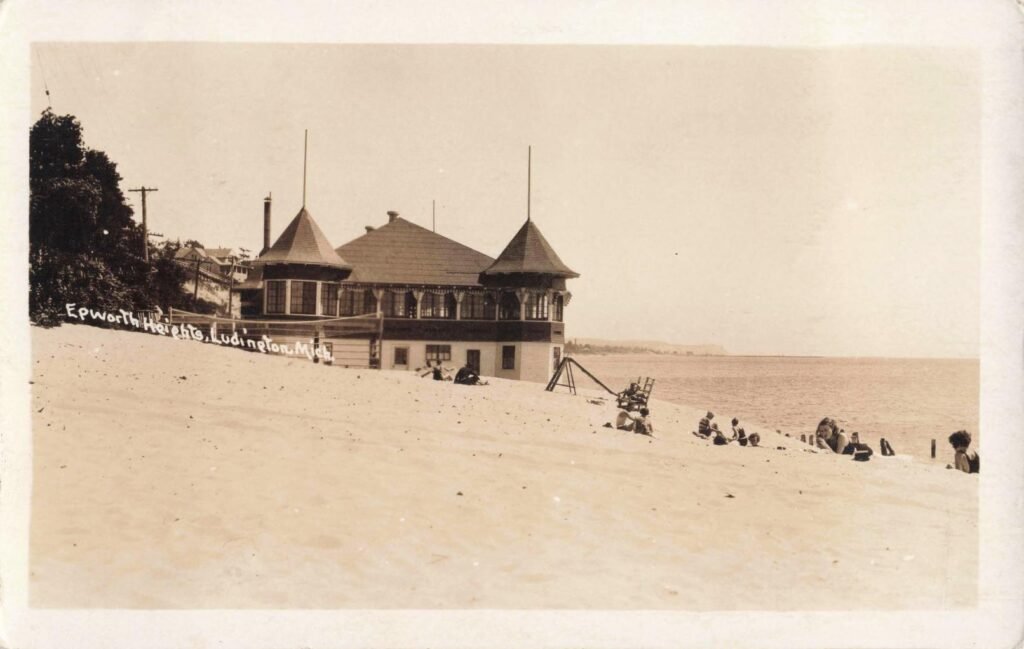

From Industrial Shore to Summer Assembly

Once logging declined, the sandy bluffs and inland lake around the former village took on a new use. In 1894 Methodist leaders chose this stretch of shore for a seasonal training and retreat center, which became known as Epworth Heights.

Cottages rose where mill buildings once stood. A hotel, auditorium, and stairways down to Lake Michigan transformed the former industrial site into a summer community. Today Epworth Heights is a private seasonal enclave, while Lincoln Lake and the mouth of the Lincoln River remain familiar landmarks for residents and visitors near Ludington.

Why Graham’s Mill Still Matters

The story of Graham’s Mill illustrates how quickly Michigan towns could change roles in the late nineteenth century. In one generation, the Graham family moved from sawing lumber in Mason County to running steamers on the St. Joseph River. In roughly the same span, Lincoln shifted from county seat and mill village to a footnote beneath a resort’s name.

Standing on the bluffs above Epworth Heights today, it is easy to see only cottages and tennis courts. The photograph of Graham’s Mill helps restore the noise, smoke, and motion that once defined this shore and ties it to riverboats churning far to the south.