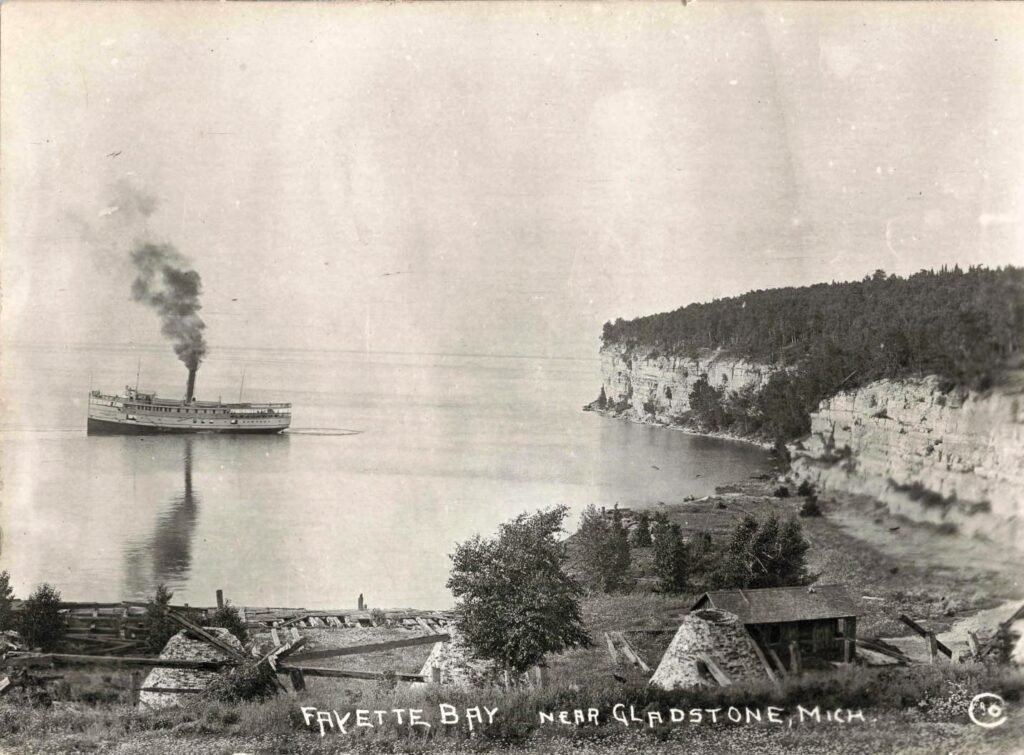

The history of Fayette, Michigan, begins in 1867, when manager Fayette Brown of the Jackson Iron Company chose a remote harbor on Michigan’s Garden Peninsula to build a new blast furnace. This site offered everything the iron works needed: a protected bay for shipping, nearby limestone cliffs to provide furnace flux, and vast hardwood forests to burn into charcoal. By 1869, the first 30-foot limestone furnace stack was lit, and a second came online soon after. Fayette was named for its founder and was built entirely by the Jackson Iron Company.

Table of Contents

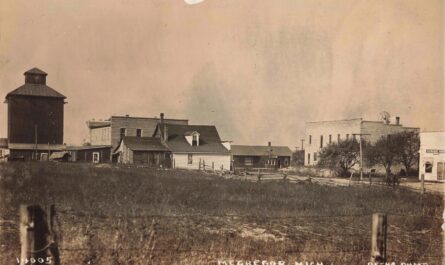

Over the next two decades, Fayette became one of the Upper Peninsula’s most productive iron towns. Its twin furnaces produced roughly 229,000 tons of pig iron from 1867 to 1891. Most of that iron was shipped to steel mills on the lower Great Lakes to be made into railroad rails and girders. The town’s roughly 500 residents lived in a neat grid of company-built houses a few blocks inland. By 1875, Fayette boasted a hotel, a school, and even a horse racing track – essentially a frontier city of its era. However, daily life revolved around the iron works.

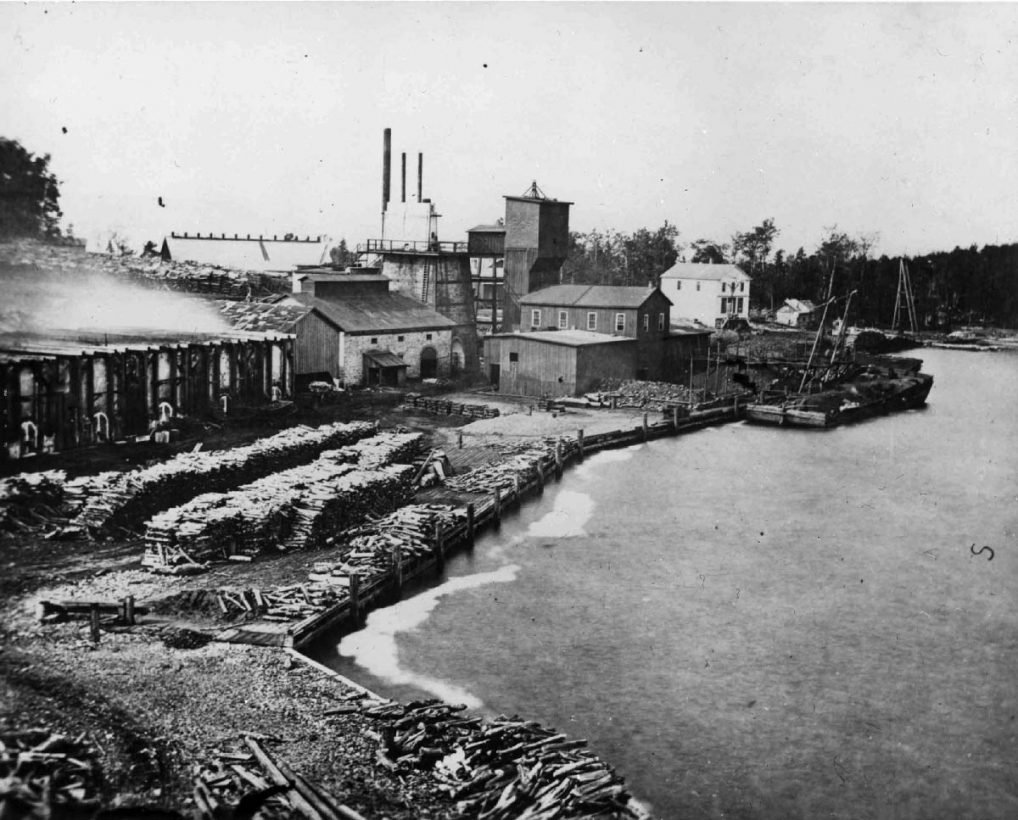

Fayette’s two-story company store circa 1870. Workers were paid in company scrip and spent it here on groceries, clothing, tools – everything they needed. A horse-drawn delivery wagon and men in caps appear in the photo, hauling supplies to the store. Behind the store were the company’s barns and sawmill, which ran day and night to cut timber and build charcoal for the furnace. Historical records emphasize this industry: Fayette had dozens of charcoal kilns on the bluff, each working 20–30 feet high and fed with local wood. During its 24 years, Fayette’s furnaces “produced a total of 229,288 tons of Pig Iron, using local hardwood forests for fuel and quarrying limestone from the bluffs”.

Video

Life in Fayette was not all work. With no nearby towns, the company provided some recreation. As the Michigan Historical Center notes, “Fayette had a coronet band, baseball team, horse racing track, school, post office, and company store”. On summer evenings, the town band would play on Main Street, and families gathered to watch local baseball games.

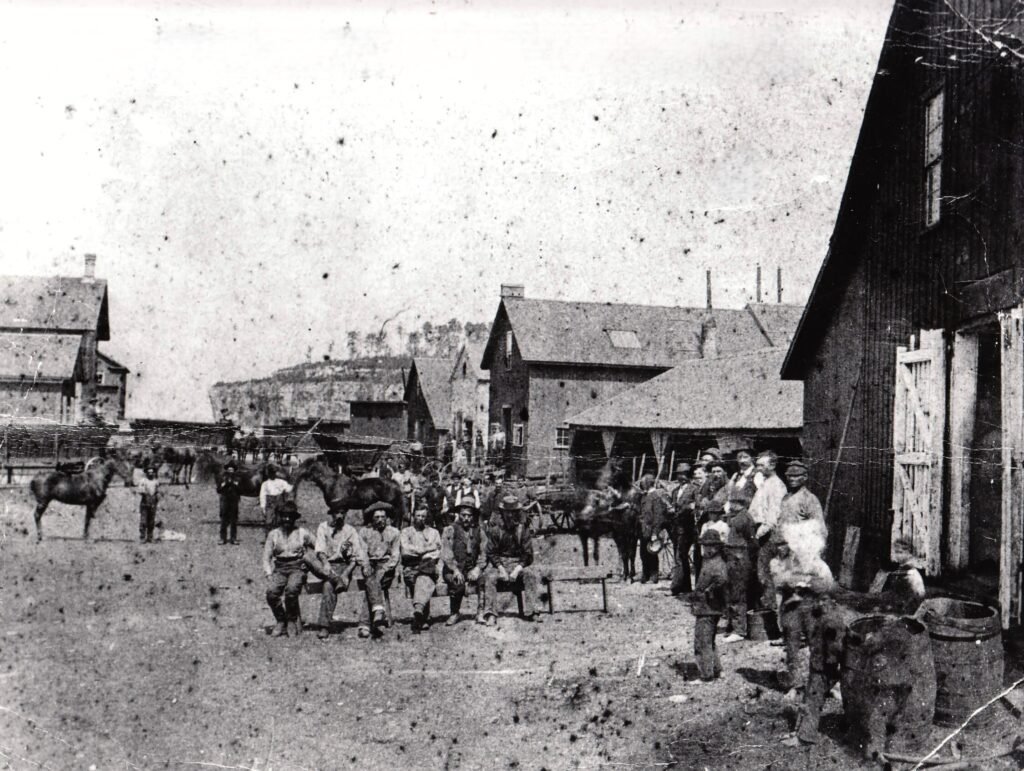

Children played around the hotel and schoolhouse in the quiet dusk. One observer wrote that Fayette’s atmosphere included “steam whistles, smoke and the whirl of engines” mixed with “children playing, [and] clattering of horses” – a vivid reminder that beneath the industrial hum, community life went on. The photo below shows Fayette’s “barn and yard crew” around 1875. The men and horses stand in front of the sawmill barns, with the limestone quarry and smokestack visible behind them. This lumberyard converted local trees into sawn lumber and charcoal – a key part of the industrial cycle.

Fayette’s workforce was surprisingly diverse for the period. Besides recent European immigrants (many were from Canada, Finland, and Norway), the town’s census records and local accounts mention a handful of African American and Native (Ojibwe) workers. These men and women lived and worked in the same company houses and shops, sharing the same smoky air and routines. Whether at the docks unloading iron or in the houses lining the streets, Fayette’s residents came from many backgrounds. Two churches – one Catholic and one Episcopal – served these families, showing how they brought their cultures with them to the Lake Michigan frontier.

Environmental Impact and Decline

All of Fayette’s iron production came at the expense of the local environment. To keep the furnaces lit, the company cut down every hardwood forest within hauling distance—dozens of brick charcoal kilns on the hillsides burned cord after cord of wood. Historical sources describe Fayette’s “huge timber piles from local forests” waiting to be burned in kilns. By 1890, surveyors reported that the surrounding hills were largely barren of mature trees. One tourist brochure bluntly notes that in 1891, “Fayette became a ghost of its former self as… forests were stripped and new methods… made pig iron less desirable”. In other words, once the trees were gone and newer steelmaking techniques took hold, the iron works had no future.

The closure came swiftly. In 1891, the Jackson Iron Company shut down Fayette’s furnaces and began selling off assets. Workers were transferred to other plants, and families left for new opportunities. Overnight, the whistles stopped, and the buildings were locked. Most of the homes and buildings were abandoned. The company store was stripped of merchandise. Left behind were stacks of unused lumber and equipment, quickly rotting outdoors.

Fayette Today: A Historic Park

Fayette’s rebirth came many years later. In 1959, the State of Michigan purchased the entire townsite for preservation. Since then, the site has been painstakingly stabilized and interpreted. Dozens of original structures now stand as a living museum: the hotel has been restored with period furnishings, the company store displays artifacts, and many cottages have been refurbished to show workers’ living conditions. Interpretive panels and a visitor center (housed in the old warehouse) explain the town’s story to guests.

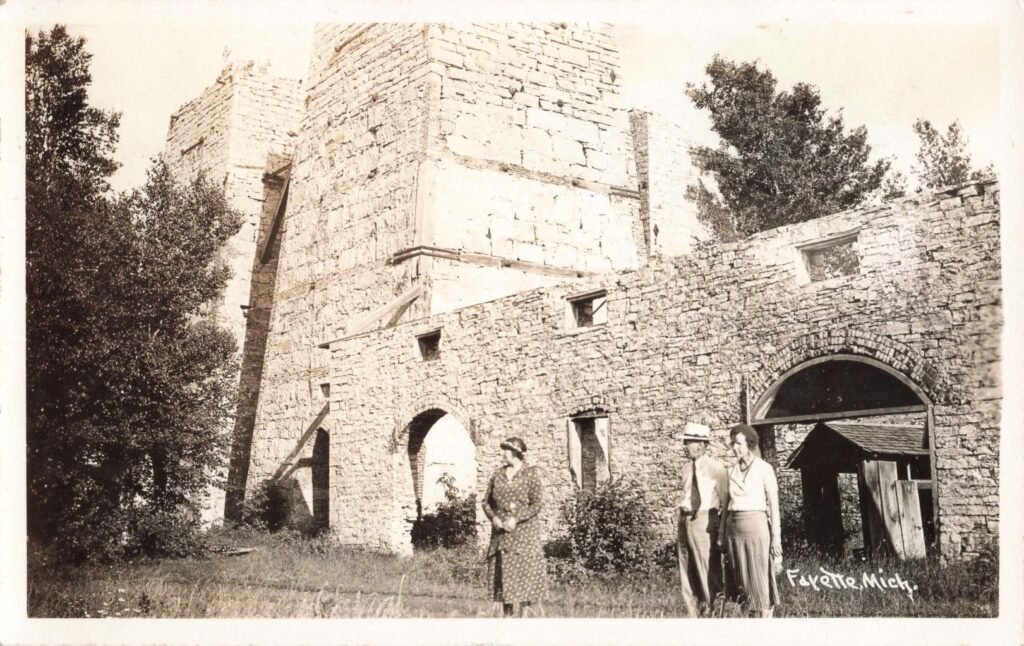

Walking through Fayette Historic Townsite today is like stepping into a postcard of 1890. The wooden sidewalks and fences have been rebuilt, and original granite curbs line the streets. In the photo below, you can see the rusticated stone furnace walls as they looked after decades of neglect – the roof and interior are gone, but the sturdy walls remain. New foundation work and exhibits now make it safe to approach these furnaces and imagine the fires that once burned inside.

The landscape has healed, too. The harbor is quiet and blue, framed by the same limestone bluffs that once offered flux. Eastern white cedar trees, some dating back over 1,500 years, now grow along the waterfront. These ancient cedars predate Fayette itself; visitors often marvel that the forest here is older than the town. The reclaimed forests and green lawns allow wanderers to picnic where iron workers once broke for lunch. Trails around the townsite follow old railroad grades and kiln sites, connecting Fayette to the broader natural beauty of the Garden Peninsula.

What to watch for when you visit

If you go, don’t rush straight to the furnace stack and leave. Walk the townsite like a resident would have. Start at the company store, picture the limits of buying on credit or scrip, then follow the route down toward the industrial waterfront. Try to picture the noise, smoke, and hauling that once filled this bay.

In learning the History of Fayette, Michigan, we see a microcosm of America’s industrial era. Fayette rose rapidly on local resources, supported a vibrant (and even multiethnic) community, and then faded as the economy and environment shifted. Today, this corner of Michigan is known less for industry and more for history and nature. The park preserves Fayette’s legacy so that this once-forgotten town – its rusting furnaces, ghostly company store, and silent woods – can tell its story to future generations.

FAQs on the History of Fayette, Michigan

Why was Fayette, Michigan abandoned?

Notes from the history of Fayette, Michigan, tell that it was abandoned because the business that built it stopped making money.It was a charcoal-iron town. The blast furnaces needed huge amounts of hardwood charcoal. After years of cutting nearby forests, wood had to be hauled from farther away, which raised costs.

Ironmaking changed. By the late 1800s, many producers shifted to coal- and coke-fired methods that were cheaper and easier to scale than charcoal iron. Fayette couldn’t compete.

When the furnaces shut down, the town had no other employer. Fayette was a company town. Once the Jackson Iron Company ended operations in 1891, most residents left quickly to find work elsewhere.

That combination—fuel costs rising, competition getting tougher, and a one-industry economy—turned Fayette into a ghost town almost overnight. Today, the buildings and furnace ruins remain because the site was later preserved as a historic park.

What is the history of iron smelting in Fayette?

The history of iron smelting in Fayette, Michigan is one of industrial ambition and environmental cost. Here’s a concise overview:

Founding and Purpose

Fayette was founded in 1867 by the Jackson Iron Company to produce pig iron—a raw form of iron used in steelmaking. The company’s managers chose the site on the Garden Peninsula for three key reasons:

Limestone cliffs nearby provided a natural flux for the smelting process.

Dense hardwood forests supplied charcoal to fuel the furnaces.

Protected harbor access on Lake Michigan allowed easy shipment of iron to Great Lakes steel mills.

The Smelting Process

Fayette’s furnaces were charcoal-fired blast furnaces, typical of the 19th century. Workers heated iron ore, limestone, and charcoal at roughly 2,800°F to extract molten iron, which was cast into ingots known as “pigs.”

Each furnace stood about 30 feet tall and operated nearly year-round.

Charcoal was produced locally in dozens of kilns, consuming thousands of cords of hardwood each year.

Between 1867 and 1891, the site produced roughly 229,000 tons of pig iron.

Workforce and Daily Life

Around 500 people lived in Fayette at its peak—many immigrants from Canada, Finland, and Scandinavia. The company built homes, a store, and a hotel to support its workers. The town was noisy, smoky, and active, but also self-contained.

Decline and Closure

By the late 1880s, two major factors doomed Fayette:

Deforestation—the surrounding forests were stripped bare, driving up fuel costs.

Technological change—new coal- and coke-fired furnaces elsewhere made charcoal iron obsolete.

In 1891, the Jackson Iron Company shut down operations. Without work, families left almost overnight, and Fayette became a ghost town.

Preservation

In the 1950s, the State of Michigan purchased the site, and it became Fayette Historic Townsite, part of Fayette Historic State Park. Today, visitors can tour the restored blast furnaces, company store, and cottages to see how a self-sufficient 19th-century iron town operated.

What is Fayette, Michigan known for?

Fayette, Michigan is known for:

A preserved 19th-century iron-smelting company town at Fayette Historic Townsite, a “living museum” where you can walk through restored buildings and the industrial ruins.

Charcoal pig iron production (1867–1891) tied to the Jackson Iron Company era, when the town existed mainly to run the furnaces and ship iron out by water.

The massive limestone blast furnace ruins and industrial complex, the signature landmark most visitors come to see and photograph.

A dramatic Lake Michigan harbor with high limestone cliffs, plus trails and overlooks that frame the townsite and shoreline.

A state park experience you can visit today, including the historic townsite, visitor center, trails, campground, boat access, and designated swim area.

Works Cited for the History of Fayette, Michigan

Michigan Historical Center. Fayette Historic Townsite. Michigan.gov, State of Michigan. Accessed 17 Dec. 2025.

Murphy, Brian. “A Window Into The Past – Fayette State Park.” Wild Places, Wild Birds, 20 Nov. 2023, twotalonsup.com/a-window-into-the-past-fayette-state-park/. Accessed 17 Dec. 2025.

“Fayette | Ghost Towns.” Historic Sites & Marker Program, NMU, beaumier.nmu.edu/ghosttowns/fayette. Accessed 17 Dec. 2025.

“Fayette, Mich.” David V. Tinder Collection of Michigan Photography, Univ. of Michigan Library. Accessed 17 Dec. 2025.

“Fayette Historic State Park & Townsite.” UP Travel Association, uptravel.com/attractions/fayette-historic-state-park-townsite. Accessed 17 Dec. 2025.