For decades in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, water was the road between Port Huron, Michigan, and Sarnia, Ontario. Before the Blue Water Bridge spanned the St. Clair River in 1938, small steam ferries carried passengers — and later, automobiles — across this international crossing. Among the many vessels that plied the river, three modest wooden steamers — Grace Dormer, Omar D. Conger, and Hiawatha — these Port Huron ferries represent a formative chapter in regional transport history.

The ferry story at Port Huron stretches back to the mid-1800s, with early craft powered by ponies, horses, and mules before steam engines became the norm. These early ferries helped build ties between Michigan and its Canadian neighbor long before fixed links existed. By the 1870s, paddle steamers had become standard on the river, and fleets grew to meet demand.

Grace Dormer – Small but Essential

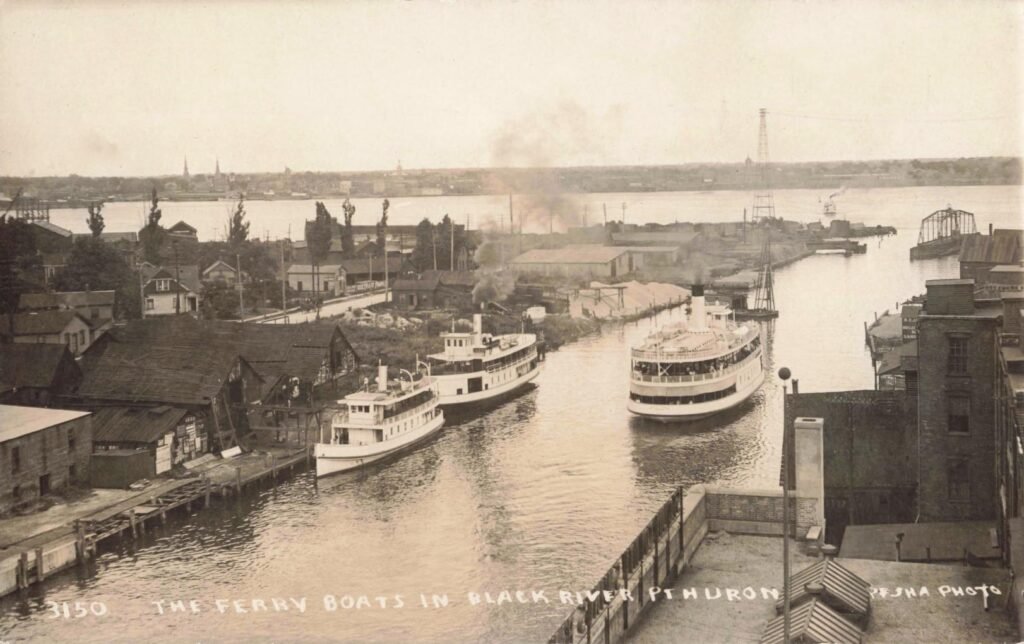

In this image from the Black River, the Grace Dormer sits on the left. Built around 1868, she was one of the smaller steamers serving the crossing, roughly 70 feet in length. For years, she made back-and-forth runs between docks at the foot of Cromwell Street in Port Huron and Ferry Dock Hill in Sarnia. Over time, the Dormer was joined by other steamers as the cross-border ferry service expanded.

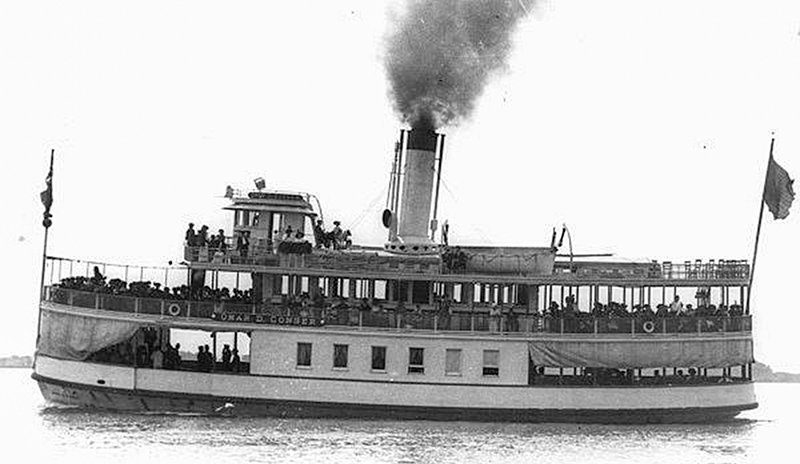

Omar D. Conger – A Tragic End

Behind her stands the Omar D. Conger, launched in 1882 and named for a prominent U.S. senator from Michigan. For four decades, she faithfully connected the two cities along the St. Clair. The Conger was described by later historians as a “diminutive” vessel, yet she became central to river travel for generations.

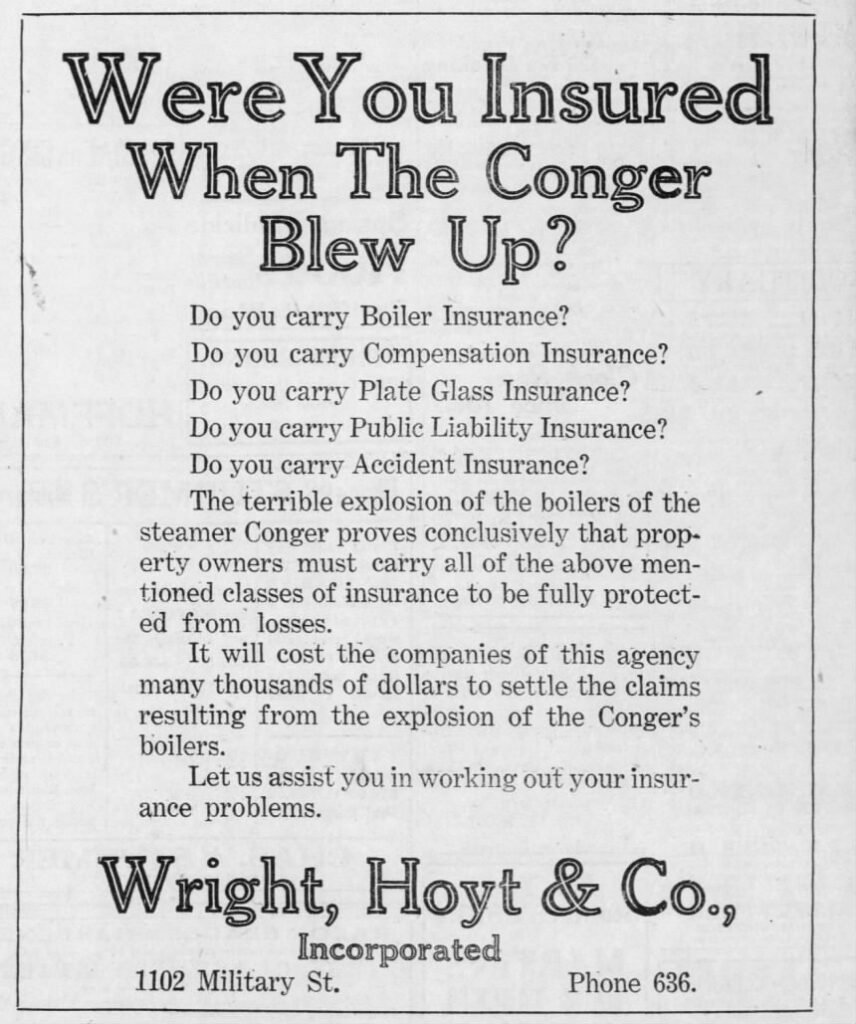

Tragically, her service ended in dramatic fashion on March 26, 1922. While docked on the Black River, the boat’s boiler — fired up for another run — suffered a catastrophic explosion. Four crewmen lost their lives, and massive debris was hurled across the waterfront, damaging nearby buildings. Miraculously, a passenger ferry approaching at the time was unharmed, and the broader community managed to absorb the shock of the event.

The Conger boiler explosion was a boon for lawyers seeking those affected by the blast.

Hiawatha – The Oldest of the Three

To the right in the photo is the Hiawatha — another wooden steamer in the fleet. While not as widely documented as the Conger, her presence reflects a growing ferry service in the late 19th century. According to ferry registries, vessels like the Hiawatha, the James Beard, and others joined the Port Huron lines through the 1880s and 1890s, serving workers, visitors, and everyday travelers alike.

The End of Port Huron Ferries- Transportation Changed After 1938

By the early 20th century, ferry service had evolved to carry not only foot passengers but also early automobiles. In 1921, larger steel ferries like the Louis Philippe and Lawrence joined the runs, capable of hauling dozens of cars. Despite this modernization, the older wooden steamers gradually became obsolete. After the Conger’s explosion, the Port Huron Ferry Company introduced purpose-built auto-carrying ships while aging wooden steamers were retired.

These ferries were more than transport machines: they shaped daily life along a busy international waterway. Long before bridges and tunnels made crossings routine, workers, shoppers, and families relied on the rhythm of steam whistles and black smoke to stay connected. Reports from the era describe constant runs tying docks on both sides of the river, often carrying thousands of souls each year.

End of Ferry Service Between Port Huron and Sarnia 1938

The era of the Grace Dormer and Omar D. Conger faded as the Blue Water Bridge opened in 1938, offering uninterrupted road access and making ferry runs less essential. Yet these humble steamers remain a vivid reminder of a time when wooden hulls linked Michigan’s shores to Ontario’s in clouds of coal smoke and the cadence of paddle wheels.