Before railroads, factories, or skyscrapers, Michigan’s economy ran on fur. In the early 19th century, no place mattered more to that system than Mackinac Island, a strategic hub linking the Upper Great Lakes. From this crossroads flowed pelts, profits, and power—and at the center of it all stood the American Fur Company Headquarters built by John Jacob Astor.

The Center of the Fur Trade in the Early 1800s

Built in 1817 on Market Street, the Robert Stewart House served as the main headquarters of the American Fur Company, controlled by John Jacob Astor, then the wealthiest man in the United States. The building combined an agent’s residence with warehouse space, a practical design for a frontier economy where business and daily life overlapped.

Astor did not invent the fur trade. Native nations across the Great Lakes region had managed trade networks for generations. What Astor built was a system that centralized and monetized those networks on an unprecedented scale. From Mackinac Island, company agents coordinated contracts, fixed prices, tracked shipments, and managed relationships that stretched hundreds of miles inland. Furs collected throughout the region were shipped east across the island, then on to New York and European markets.

Mackinac Island Was Economic Center of the Northwest Territories

Inside the Astor House, clerks kept detailed ledgers listing pelts by type and quantity. Agents negotiated terms with traders and trappers. Decisions made in these rooms shaped livelihoods far beyond the island. The building functioned as both a nerve center and a symbol of American commercial expansion into the Great Lakes.

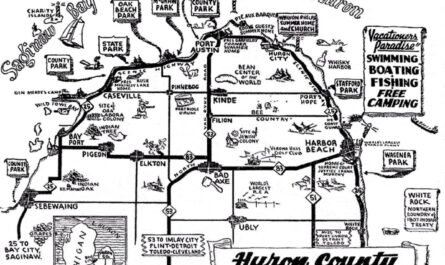

The Fur Trading Routes of the Upper Great Lakes

Mackinac Island became the hub of the Upper Great Lakes fur trade because geography left traders little choice. Sitting in the Straits of Mackinac, the narrow passage between Lake Michigan and Lake Huron, the island lay directly in the path of nearly every major canoe route. Furs collected from Lake Superior, interior river systems, and the Lake Michigan shoreline all funneled toward this choke point. Water, not roads, moved the economy, and Mackinac stood where inland rivers met open lakes.

These routes were not created by Europeans. Indigenous nations—including the Odawa, Ojibwe, and Potawatomi—developed and maintained the trade networks long before French, British, and American traders arrived. Companies like the American Fur Company later centralized the system, using Mackinac Island to sort pelts, set prices, and direct shipments east. By the early 19th century, controlling Mackinac meant controlling the flow of fur, money, and influence across the Upper Great Lakes.

Mackinac Island’s Social Life Centered on the Trading Post

The headquarters also shaped Mackinac Island’s social life during the 1820s and 1830s. Company agents ranked among the island’s most influential figures, hosting gatherings and exerting informal civic authority. Economic power and social standing moved together, and the fur company’s presence affected nearly every aspect of daily life.

For a time, the system worked. Profits grew, Astor’s fortune expanded, and Mackinac Island thrived as a commercial hub. But the success carried consequences. Overtrapping reduced animal populations. Fashion trends shifted away from fur hats. By the 1830s, the industry that had built the island’s economy was weakening. The American Fur Company gradually lost its dominance, and the island began transitioning toward military use, tourism, and seasonal commerce.

The Robert Stewart House Lives On

What remains today is a physical reminder of that earlier era. Portions of the original structure survive as part of the Stuart House City Museum. Visitors walking through its rooms are standing in one of the most important business addresses in early America.

The Robert Stewart House is part of a larger story about Michigan’s role in national history. Long before automobiles defined the state, Michigan sat at the center of a global trade network. Mackinac Island was not a remote outpost, but a command post of early American capitalism. The ledgers kept here helped shape fortunes, industries, and the future of the upper Great Lakes.

Sources Cited

-

City of Mackinac Island — “History” (Stuart House City Museum page)

Used for: the American Fur Company “Agent’s House” (built 1817) and the multi-building AFC office complex on Mackinac Island.

-

Mackinac State Historic Parks — “What’s on the Other Side of the Lake? Green Bay!”

Used for: the Michilimackinac–Green Bay link, and the Fox River as a main artery to interior trading grounds via the Mississippi-connected route system.

-

Wisconsin Historical Society — “Fur Trade Era: 1650s to 1850s”

Used for: the Fox–Wisconsin route description (Wisconsin River ? Portage ? Fox River ? Green Bay) as a major inland corridor tied to Great Lakes trade.

-

Wisconsin Shipwrecks — “Use of Water Routes During the Fur Trade Era”

Used for: shoreline travel from the Straits of Mackinac across northern Lake Michigan into Green Bay, then up the Fox River and portage to the Wisconsin River.

-

Chicago History Museum — “American Fur Company records” (finding aid)

Used for: Michilimackinac as an American Fur Company headquarters area in the Old Northwest (context for Mackinac’s administrative importance in the trade era).

-

Mackinac State Historic Parks — “American Fur Co. Store & Dr. Beaumont Museum”

Used for: Market Street location context for American Fur Company-era operations on Mackinac Island (Fort & Market area).

-

Parks Canada History (E.W. Morse) — “Fur Trade Canoe Routes of Canada / Then and Now” (PDF)

Used for: canoe route context involving departures from Mackinac toward Sault Ste. Marie (supporting the Lake Superior / St. Marys River connection in fur-trade travel networks).

-

The Canadian Encyclopedia — “Fur Trade Route Networks”

Used for: broader fur-trade route-network framing (how major inland/watershed routes connected to Great Lakes corridors).