Northern Michigan’s History of Wolverine, Michigan, is a remarkable tale of adaptation. This small village in Cheboygan County went through dramatic transformations between 1890 and 1940. Founded in the lumber era and later reinvented as a tourist stopover, Wolverine’s journey reflects the broader economic and environmental history of the Great Lakes region. We’ll explore Wolverine’s founding, its logging boom, the coming of the railroad, the role of the Sturgeon River and a state fish hatchery, the development of local infrastructure, connections to Native American history, and the village’s transition into an automobile-era tourism point. Vintage photographs and postcards help bring this forgotten history to life.

Video – History of Wolverine Michigan: 9 Stark Lessons From a Northwoods Boomtown

Founding of Wolverine – Timber, Trails, and a Post Office

Wolverine was settled in 1874, when Civil War veteran Jacob Shook and his sons homesteaded land in what was then an unbroken forest. They were drawn by timber – the vast stands of white pine that covered northern Michigan. The area had long been traversed by Odawa (Ottawa) and Ojibwe people, whose trails and seasonal camps dotted the region. In fact, Wolverine lies near the Inland Waterway, a route Native tribes used for centuries. By the 1870s, however, the U.S. government had forcibly removed many Native families from these lands (the infamous Burt Lake Burn-Out of 1900, just 15 miles away, saw an entire Ottawa-Chippewa village burned to oust its inhabitants). The incoming settlers, like Shook, followed old indigenous pathways to reach this area.

Initially, the settlement around Wolverine was called Torrey, and it was platted under that name in 1881. However, when local pioneer George Richards applied for a post office, he requested the name “Sturgeon City” (after the Sturgeon River). The U.S. Post Office had other ideas. Perhaps finding “Sturgeon City” redundant or confusing, they designated the post office Wolverine, after Michigan’s nickname, “The Wolverine State.” It’s worth noting that actual wolverines were exceedingly rare in Michigan – the last confirmed sightings were in the early 1800s – so the town’s name was more a boastful symbol than a literal description.

The post office was established in 1881, with George Richards as postmaster. Before this, Richards walked nearly 25 miles to Gaylord and back each week to get mail, trudging along a crude footpath through swamps and forests. The new post office spared Wolverine’s settlers that arduous task and firmly planted the community on the map. By 1890, the village site had a few log cabins, a general store, and a regular mail service – the fundamental beginnings of a town.

Logging Boom and the Railroad Arrive

In the 1890s, Wolverine boomed – literally, with the booms of felled trees and the whistle of locomotives. The timing was perfect. Michigan’s lumber industry was reaching its peak, and Cheboygan County’s forests were being feverishly harvested. The Jackson, Lansing & Saginaw Railroad (later part of Michigan Central) extended its line north through Wolverine to Mackinaw City by 1881, just as logging camps proliferated in the area. This railroad connection was revolutionary. It allowed timber companies to ship logs and lumber south to city markets efficiently, and it allowed people and supplies to pour in.

Wolverine’s population exploded from just 18 residents in 1881 to about 1,000 residents by 1891. Most of these newcomers were either logging lumberjacks or railroad workers, according to contemporary accounts. Sawmills sprang up near town, including a veneer mill started by Joe and Fred Start in the early 1880s. These mills processed logs into lumber, shingles, barrel staves – anything a growing America needed.

The town’s layout quickly expanded along a traditional “Main Street.” Businesses catering to lumbermen – like general stores, saloons, barbershops, and boarding houses – lined the street. There was money to be made, and the town thrived. In 1903, Wolverine officially incorporated as a village, reflecting its newfound permanence. Around this time, two local banks opened to handle the commerce (People’s Bank c. 1900 and Wolverine State Bank shortly after).

A local newspaper, the Wolverine Courier, began publishing in the early 1900s, evidence of civic pride and a growing population. The village even attracted a notable professional: Dr. Marion Goddard, who became the first female physician in all of northern Michigan when she set up her practice in Wolverine before World War I. It was highly unusual for a rough lumber town to have a woman doctor making house calls (she charged $1 per visit, medicine included!), and this fact is an insight into Wolverine’s character. This place could embrace progressiveness amid its frontier masculinity.

Railroads were Wolverine’s artery. In the summer, as many as six passenger trains per day passed through, some stopping at Wolverine’s depot. The village’s first proper train depot was built in 1906. Next to it stood a tall water tower, used to refill steam locomotives. The depot quickly became a social focal point. It welcomed incoming lumbermen and occasional tourists and sent off carloads of logs, maple syrup, and even tourists’ trunks.

By 1905, Wolverine’s population reached its all-time high of roughly 1,800. On Saturdays, after the lumber camps paid their men, the town filled with lumberjacks looking to spend their hard-earned wages. One local recollection noted that Saturday nights nearly doubled Wolverine’s population as woodsmen flocked to town. They packed the saloons and pooled around street vendors – a scene familiar in logging towns of that era.

However, the forest resources were finite. Year by year, the great pines fell. Logging companies moved on to new stands of timber or closed up shop. The once roaring mills slowed. There’s an often-cited statistic that Cheboygan County’s mills produced over 100 million board-feet of lumber annually in the early 1890s. Still, by the 1910s, that output had plummeted as local timber was largely exhausted.

Additionally, rampant logging left dry brush that led to catastrophic forest fires, further devastating the woods by 1908. By the 1920s, the timber era was effectively over in Wolverine. The village that had boomed so dramatically now faced an economic bust.

The Sturgeon River: From Log Drives to Fish Hatcheries

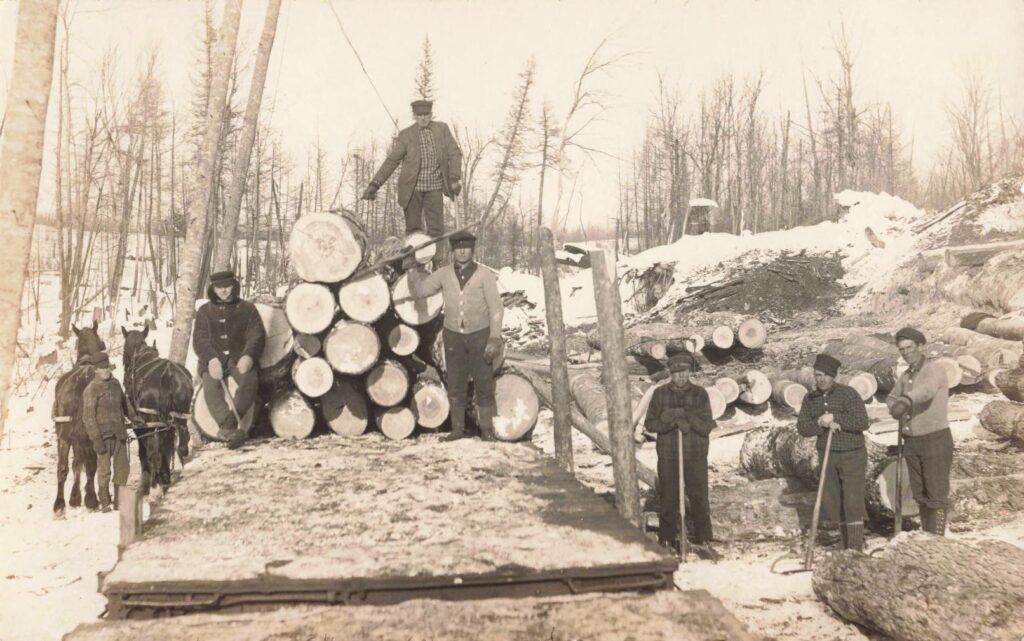

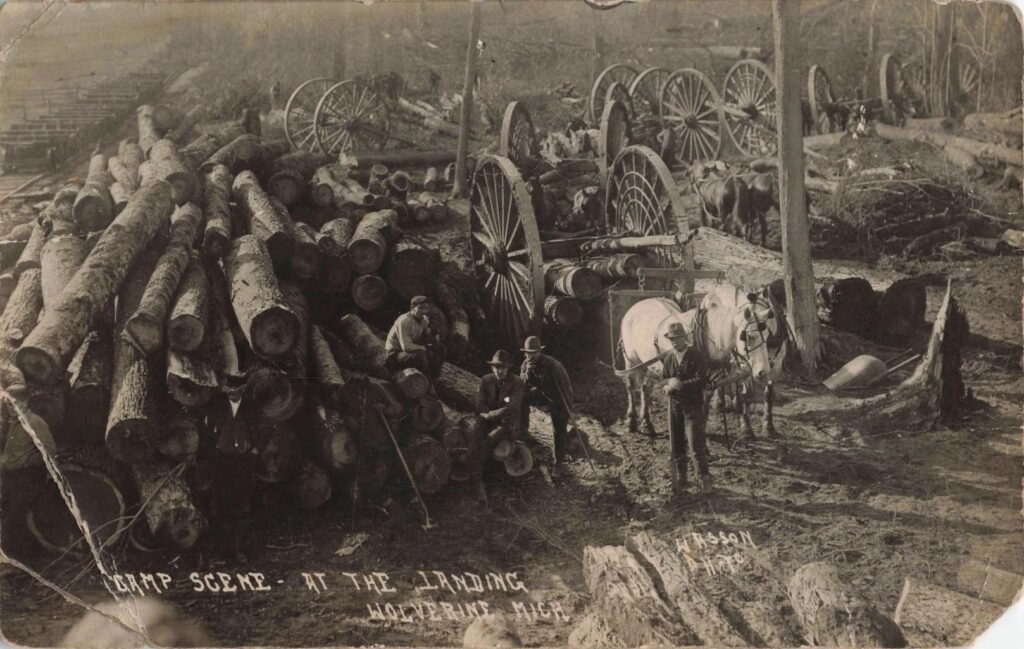

Wolverine’s natural setting is defined by the Sturgeon River, a swift, clear stream that courses right through town. During the logging boom, the Sturgeon was essentially a log highway. In spring, “log drives,” lumberjacks rolled tens of thousands of logs into the river’s swollen currents to float them toward sawmills downstream. “The river was a real asset to the logging industry…this is how they moved the logs down the water to the sawmills,” recalls local historian Dave Bird. Men with peavey poles guided the timber and broke up logjams. Place names like “The Landing” near Wolverine mark spots where logs were temporarily yarded or loaded. One vintage photo, labeled “Camp Scene, At the Landing,” shows lumbermen and horses on a riverbank, stacked high with logs, capturing a moment from these log drive operations.

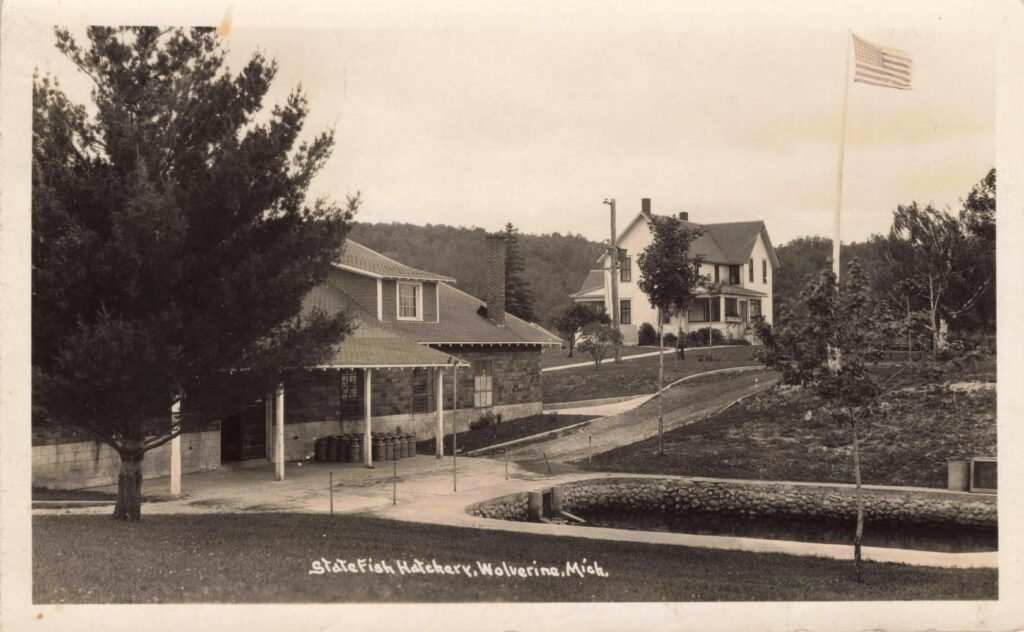

After the lumber boom subsided, the Sturgeon River took on a new role: conservation and recreation. In the early 1930s, as part of efforts to employ men during the Depression and restore wildlife, Michigan established a State Fish Hatchery in Wolverine. It was built on the site of a former mill, leveraging the river’s cold, clean water to raise game fish. By 1934, this hatchery’s ponds employed 90 local men – many former lumberjacks – in rearing fish instead of cutting trees. They primarily raised trout fingerlings to stock streams across Michigan. This was a significant shift for the town’s relationship with its river: once used to exploit resources, now used to replenish them.

The Wolverine fish hatchery operated for roughly a decade (a Department of Natural Resources report notes it began in 1922 and was “abandoned” by 193, though local sources suggest work continued into the mid-1930s). The legacy of that hatchery is still visible – some pond structures remained for years, and the idea of conserving natural resources took root in the community. In modern times, canoeists and anglers love the Sturgeon River, and even efforts to reintroduce lake sturgeon (the fish) to the river have been led by the local Odawa tribe in partnership with conservation groups, bringing the story full circle to the indigenous connection.

Infrastructure and Community Life

During Wolverine’s formative years (1890s–1920s), the community developed the trappings of a stable town. A school district was organized in 1882, and by the turn of the century, Wolverine had multiple classrooms for the influx of children. Churches took root: a Congregational church was built as early as 1883 (using donated lumber from a local mill) and a Methodist church in 1893, serving the spiritual needs of residents and offering a bit of refinement in a rough town. Civic organizations like the IOOF (Odd Fellows) lodge were established – Wolverine even had an IOOF Hall downtown, which doubled as a community gathering space.

One cannot overlook Wolverine’s post office and Main Street when discussing infrastructure. The Post Office, opened in 1881, was crucial for connecting Wolverine to the outside world. In 1910, Wolverine’s post office was photographed as a simple one-story structure with “Post Office” painted proudly on its false front. This building likely housed other offices or a general store as well – a common practice in small towns.

Wolverine’s Main Street itself was the artery of daily life. In the 1910s, it was a dirt road (which turned to mud in spring) lined with wooden sidewalks. Photos show stores like Peterson’s Meat Market (Charles Peterson’s butchery, which at one point processed “seven head of cattle daily” around 1903), a harness and shoe repair shop, possibly a bakery, and hotels. Oil lamps or early electric lights hung from awnings to illuminate the street at night.

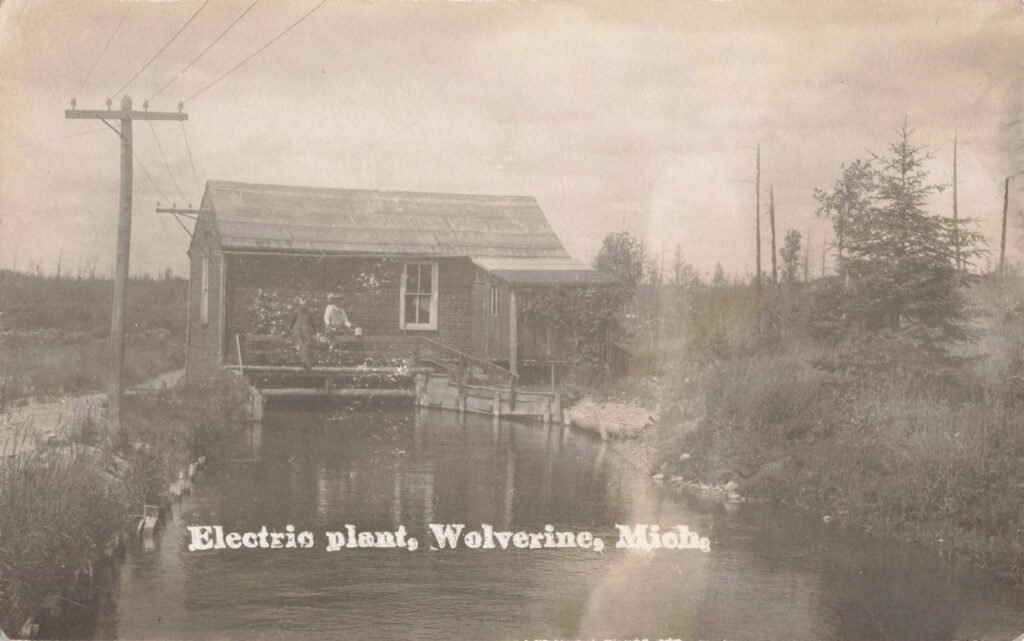

By roughly 1908, local citizens undertook improvements like re-grading East Hill Road with teams of horses, and later upgrading to gravel or pavement as automobiles became common. These were big quality-of-life changes. The arrival of electricity and telephone service in the 1910s also modernized Wolverine. It is noted that by the 1920s, Wolverine likely had telephone connections, as many northern Michigan villages were linked by then.

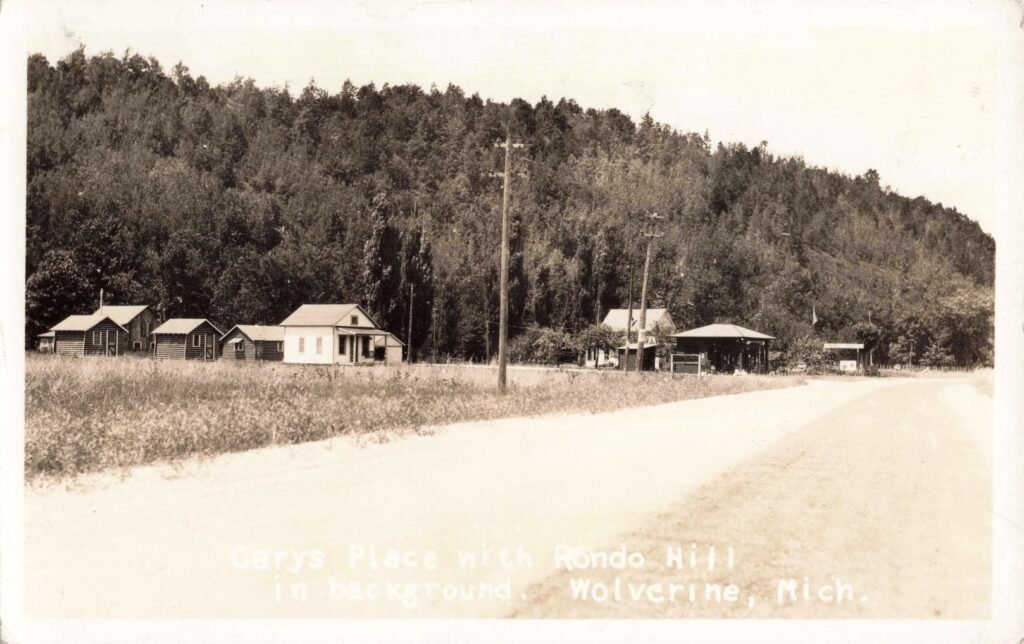

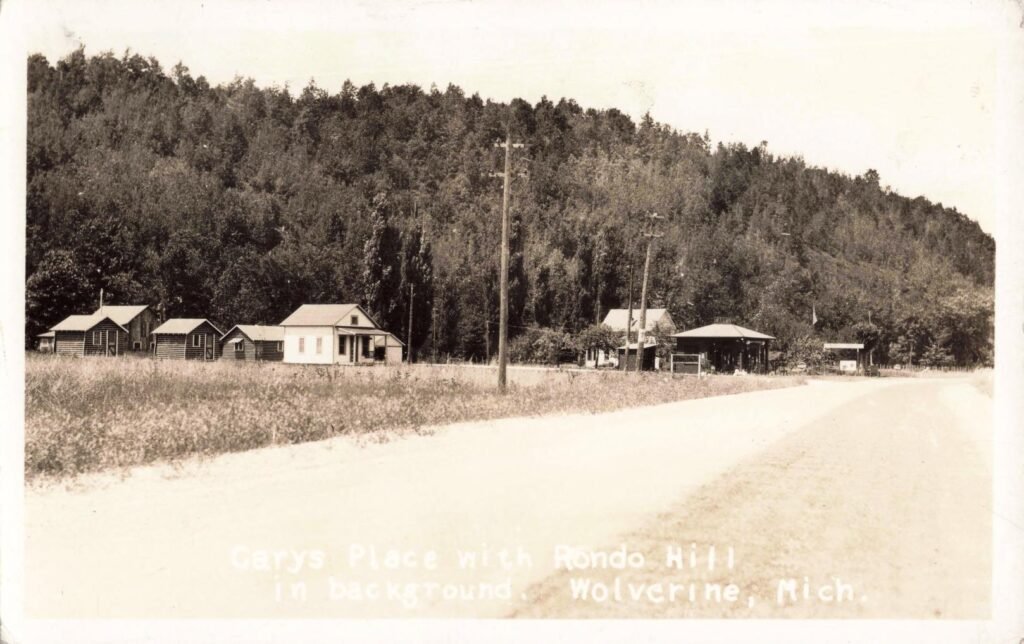

Another notable piece of infrastructure: Scott’s Hill and Rondo. A farming settlement named Rhondo (or Rondo) just outside Wolverine grew around an old mill site and a depot on the railroad. Mark Schott homesteaded a farm there in 1884, and the hill became known as Scott’s Hill – later the location of “Gary’s Place” roadhouse in the auto era. Such satellite communities contributed to Wolverine’s economy, providing farm produce and additional train passengers.

Socially, Wolverine was known for events such as the Cheboygan County Fair, held there in the early 1900s. The fair brought in folks from all over the county for horse racing, exhibits, and carnival attractions. It was a highlight of the year and boosted local businesses. Wolverine’s own Lumberjack Festival is a modern continuation of that spirit, celebrating the area’s heritage – though it started long after 1940, it harkens back to the boom times when lumberjacks were the local celebrities.

Native American Connections

While Wolverine itself did not have a large Native American population during 1890–1940 (due to earlier displacements), the region’s Odawa and Ojibwe heritage is an important backdrop. The very name of the Sturgeon River (Namewegon in Anishinaabemowin) indicates the significance of this area for Native people – lake sturgeon were a vital resource and cultural symbol for the Anishinaabe—the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa and the Sault Ste. The Marie Tribe of Chippewa has maintained ties to its traditional territories around Cheboygan and Emmet Counties. In the 1930s, many Anishinaabe people in northern Michigan were organizing to preserve their communities, even as Wolverine’s residents were shifting toward tourism.

One tangible intersection of Native and Wolverine history: Indian River, the town just 7 miles north, was named after a critical Ottawa settlement. Indian River was a place where Indigenous families lived and traded in the 19th century. Travelers in the 1920s driving through Wolverine to Indian River might have visited the famous Cross in the Woods or bought crafts from Native vendors there. Also, starting around the 1940s, members of local Odawa and Ojibwe communities were involved in guiding fishing or hunting trips for tourists, including on the Sturgeon River near Wolverine. This hints that, although Wolverine’s main historical narrative centers on Euro-American settlement and industry, the Native presence persisted in subtle ways. Recent efforts (2020s) by the Little Traverse Bay Bands to stock sturgeon in the river at Wolverine show a rekindling of Indigenous stewardship in the area, an inspiring footnote to the story.

From Stopover to Destination: Tourism and Roadside Commerce

By the late 1920s and into the 1930s, Wolverine found a new purpose as an auto-era stopover. The bust of logging coincided with the boom of automobile travel. Wolverine sat along the main route (Old U.S. 27) between Michigan’s populous southern cities and the Straits of Mackinac – essentially halfway up the Lower Peninsula. As U.S. 27 was paved by the 1930s, tourist traffic increased dramatically. Wolverine’s leaders and business folks adapted by promoting the area’s natural attractions: clean rivers for fishing, ample woods for hunting, and a central location near lakes and state parks.

Entrepreneurs opened roadside accommodations. The Wolverine Hotel, which had been around since the turn of the century, updated itself for motorists – adding parking space for cars and advertising “modern rooms.”

New establishments popped up, too. For example, the Hillcrest Inn opened on a hill south of town during the 1930s. It offered cabins and a small motel for travelers, along with a gasoline pump out front (common for inns of that era to double as gas stations). The Hillcrest Inn became known for its scenic overlook of the Sturgeon River valley and was a popular overnight stop in the 1940s and 50s (a 1951 postcard of Hillcrest Inn shows a tidy white building with green shutters, surrounded by cars of the era.

Another notable business was Rainbow Camp, mentioned earlier. This was a classic “tourist camp” featuring rustic log cabins and campsites. It prominently featured a Gulf Gas Station at its entrance, as a 1945 real photo postcard shows (captioned “Wolverine, Michigan – Gulf Gas Station at Rainbow Camp”). Travelers could refuel their vehicle, rent a cabin for the night, and perhaps enjoy a home-cooked meal at Rainbow Camp’s diner. Rainbow Camp capitalized on the post-1930 trend of families taking road trips. It was situated along the Sturgeon River, allowing guests to fish or swim. These roadside businesses signaled Wolverine’s shift into the tourism economy.

Tourism also brought auto-related commerce: garages for car repairs, general stores selling camping supplies, and eateries. By 1940, one could find places in Wolverine like “Gary’s Place” (a roadhouse near Scott’s Hill), “Sevener’s Cabins”, and other small mom-and-pop resorts. The New Deal era even saw the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) working in nearby forests to plant trees and build park facilities, which in turn drew more visitors to the region. Wolverine marketed itself as “The Heart of Northern Michigan”, convenient to lakes and wilderness.

It’s important to note that tourism did not make Wolverine wealthy – the town never again reached the population or economic output of its 1905 logging peak. But tourism and roadside commerce did stabilize the community. While many former logging towns became ghost towns, Wolverine survived. By 1940, about 500 people lived there, and the village was quiet but intact. Visitors in the late 1930s might have described Wolverine as a sleepy, friendly stop on a long drive north, with locals eager to tell stories of the “old days” when the town was wild and rowdy.

History of Wolverine Michigan – Legacy and Preservation

The period from 1890 to 1940 defined Wolverine’s character. The legacy of logging is still evident in Wolverine’s identity – the local school mascot is the Wolverines, evoking toughness, and the town holds an annual Lumberjack Festival each summer to celebrate its past. Many descendants of the original pioneer families still live in the area, often with cherished stories of their ancestors’ exploits in the lumber camps or on the railroad. The forests around Wolverine have largely grown back, erasing the once barren landscapes left by the 1900s clear-cutting. In a way, nature healed itself over the decades, and Wolverine transitioned from extracting resources to valuing them for recreation and quality of life.

Historically, some landmarks have been preserved or remembered. The old railroad depot (if it had survived) would have been a priceless artifact; unfortunately, it likely was demolished after passenger service ended. However, the Sturgeon River remains the same winding, fast stream that has seen logs, canoes, and sturgeon swim through its waters. The concept of conservation introduced with the fish hatchery continued in local practices – nearby, the Oden State Fish Hatchery (opened in 1921 in a neighboring county) took over much of Michigan’s fish rearing, and Wolverine’s brief hatchery is commemorated as part of that statewide effort.

Additionally, tribal recognition of events like the Burt Lake Burn-Out has grown, leading to historical markers and increased awareness of Native history in the Wolverine area (though not directly in the village). This adds an important layer to the appreciation of local history – acknowledging all who walked this land.

In summary, the History of Wolverine, Michigan, from 1890 to 1940 is a microcosm of northern Michigan’s broader story. It’s a tale of boom and bust: an economic boom through logging, a bust when the forests were depleted, and then a smaller resurgence through tourism. It’s also a story of resilience – how a community adapts when its reason for existence vanishes. Wolverine’s residents pivoted from lumber to fish, from axes to auto camps. They endured the Great Depression by finding new ways to use their natural setting. Today, Wolverine is a tranquil village with a population under 300, but visitors can still sense the echoes of its past. Whether you’re driving through on Old 27 or paddling the Sturgeon River, you’re experiencing the final product of those transformative years. Wolverine’s history is not widely known, yet it is deeply embedded in the fabric of Michigan’s north woods heritage. From the logs that once jammed the Sturgeon to the tourists who later jammed the highway, Wolverine has quietly witnessed a grand saga of change.

Photo Captions:

- State Fish Hatchery Ponds, 1930s: Built on an old mill site, these ponds raised trout and provided jobs after the lumber crash.

- Hillcrest Inn, 1940s: Roadside motel and gas station on US-27 in Wolverine; part of the village’s reinvention as a tourist stop.

History of Wolverine Michigan is a testament to the adaptability of small towns. It highlights how Wolverine leveraged its natural resources, then later its natural beauty, to survive. If you ever find yourself in Wolverine, pause for a moment. Look at the regrown forests and the flowing Sturgeon River. In those elements lies the living memory of a community that refused to fade away with the last log drive. Wolverine’s past continues to inform its present, making it a quietly rich destination for history enthusiasts and travelers alike.