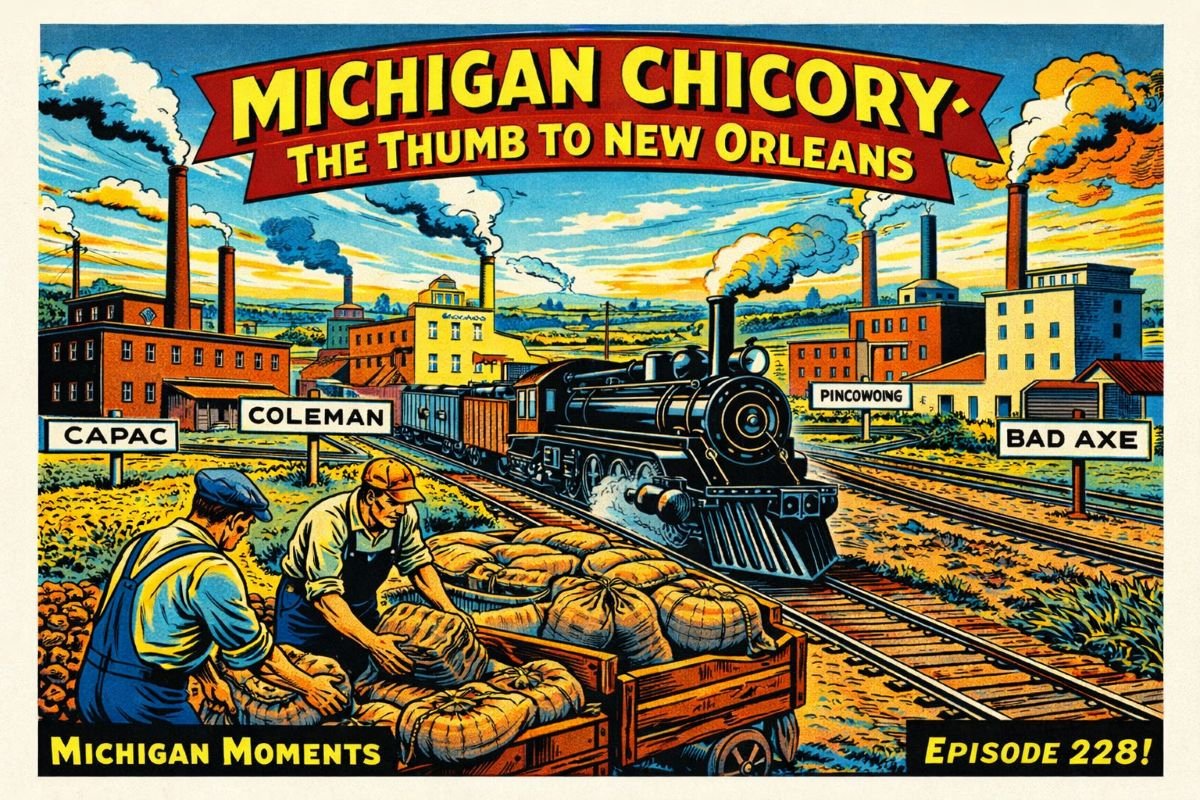

In the early 1900s, Michigan grew more than the crops most people name today. Alongside sugar beets, beans, and grains, farmers in the Thumb and east-central counties raised chicory — a root crop that could be roasted and ground, then mixed with coffee. Michigan chicory production gave farmers an easy-to-grow cash crop. It also gave housewives an opportunity to stretch their coffee budget.

Table of Contents

Video – The Dominance of Michigan Chicory

Mid-Michigan Chicory Growing

Chicory was never the biggest piece of Michigan agriculture. But it was big enough to leave a paper trail of postcards, ads, and newsprint — and big enough that a 1939 newspaper story framed Port Huron as a national center for chicory manufacturing.

This is the story of how a simple weed became a high-end root crop for Michigan farmers, and why rail lines mattered as much as farm rows.

Vannesta Bros Chicory in Capac & Colemen

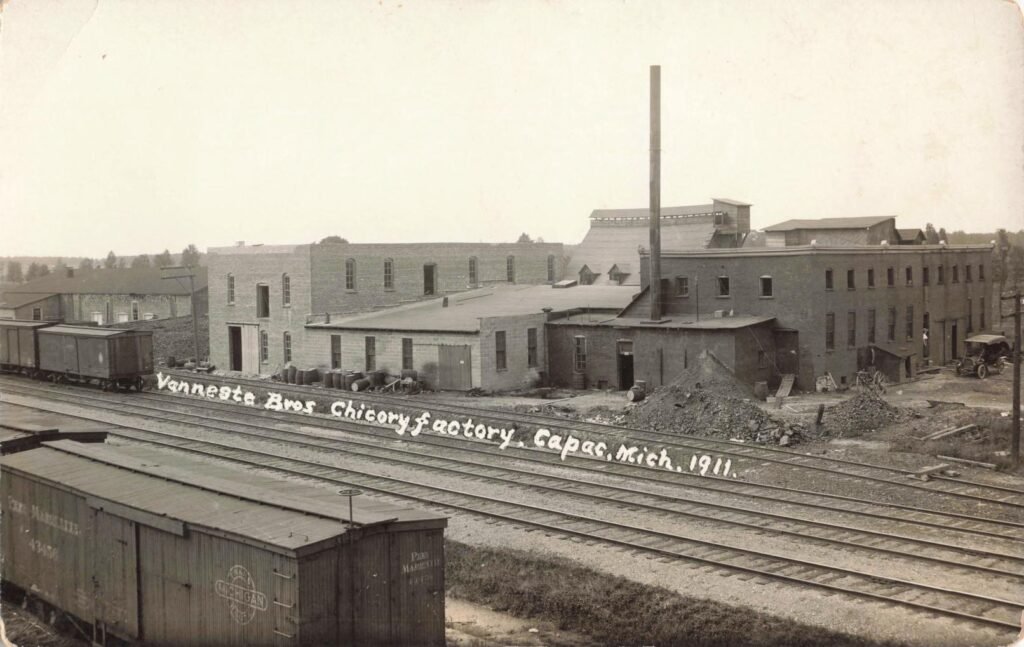

Chicory production in Michigan was truly statewide. In the thumb-area town of Capac (St. Clair County), the Vannesta Brothers built a chicory roasting mill by 1911. A period photo shows their brick factory by the tracks, labeled “Vannesta Bros Chicory Factory, Capac, Mich.” This plant processed local farms’ chicory roots into ground coffee substitutes.

Not far away in Coleman (Midland County), the same Vannesta family ran another plant. The Coleman factory (pictured) looks much like Capac’s – a modest factory building with a water tower – and similarly turned Midwest chicory into export goods.

Frank Chicory Co. In Pinconning

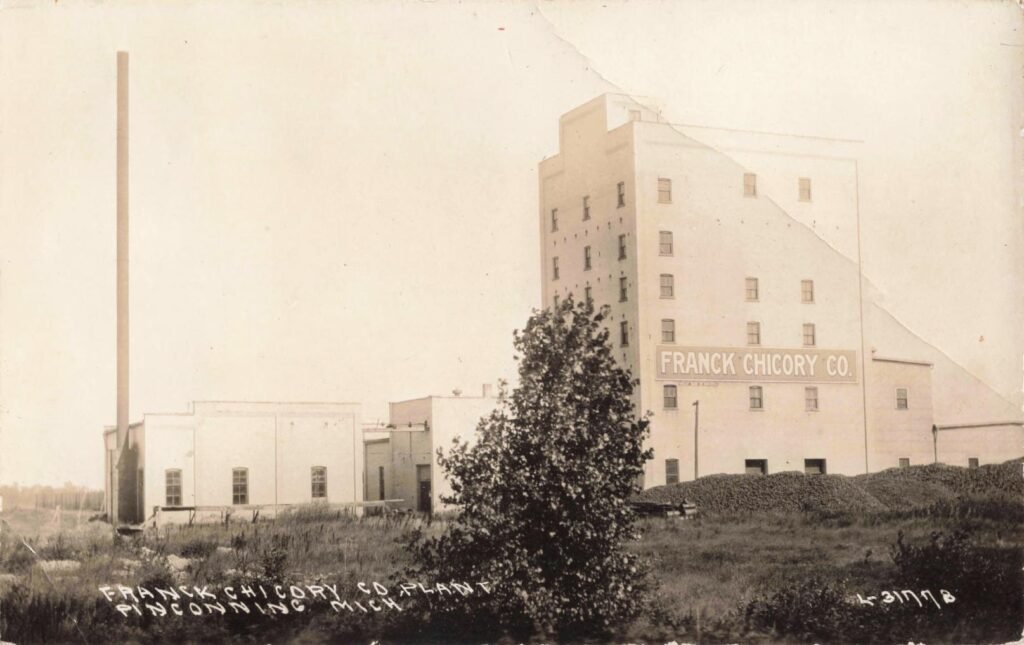

In Pinconning (Bay County), the Franck Chicory Company operated a larger mill. An old postcard identifies the Pinconning plant as the “Franck Chicory Co. Plant, Pinconning, Mich.”. Franck’s factory was active in the early 1900s and reportedly employed around 100 people at its peak. It drew Michigan chicory from Bay County farms and, like the others, shipped roasted chicory by rail to markets.

Schanzer Chicory Plant Linwood

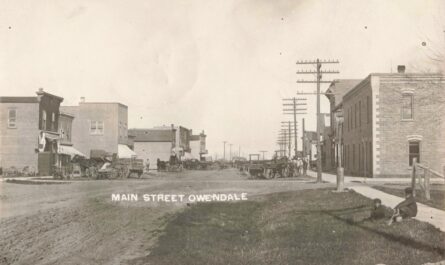

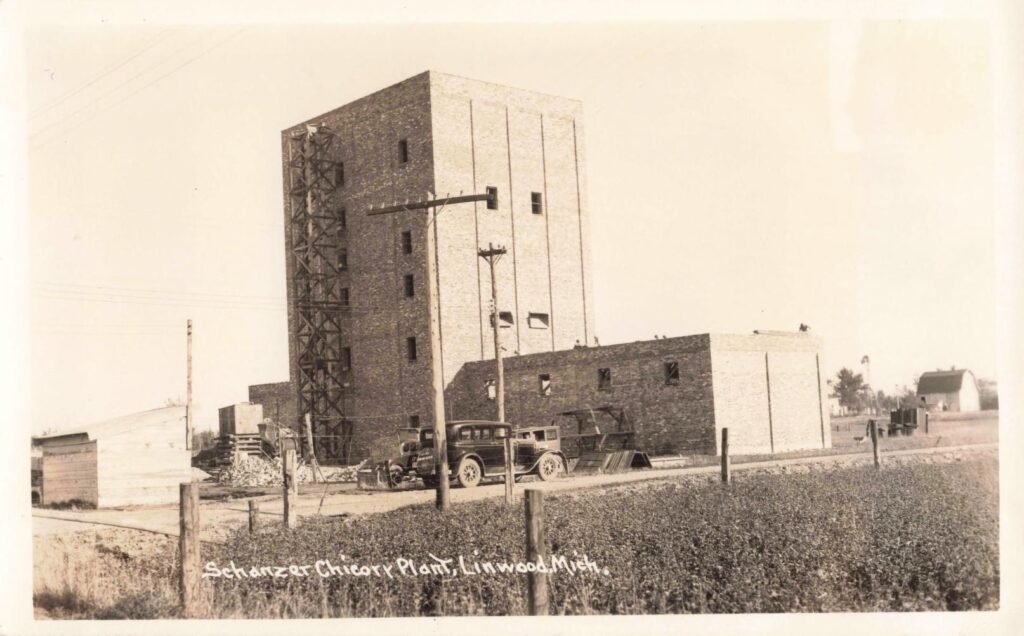

Meanwhile, in Bay County’s village of Linwood, the sign says “Schanzer Chicory Plant”. R.E. Schanzer, Inc. of New Orleans set up this drying mill in the early 1930s. Although exact dates are not on record here, local histories note that Schanzer contracted with Michigan chicory farmers around 1933. The Linwood plant expanded the network even further, showing that southern companies took advantage of Michigan’s good soil and rail links.

Bad Axe’s Chicory Plant on the Railroad

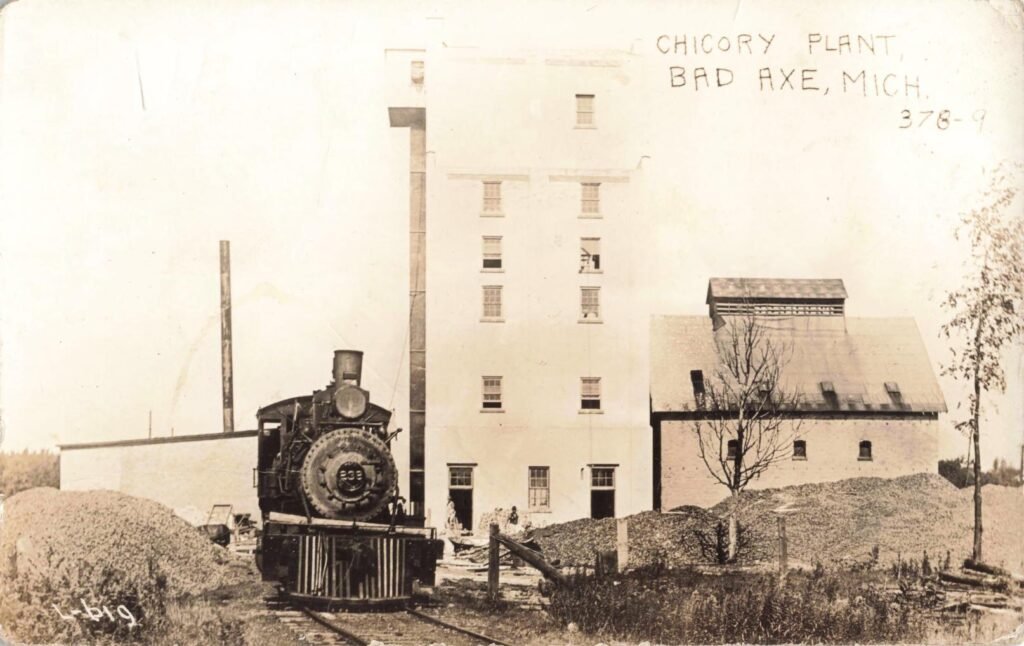

One postcard makes the industrial side of chicory impossible to miss.

The image is labeled “Chicory Plant, Bad Axe, Mich.” A steam locomotive sits on the tracks in the foreground. Behind it is a tall mill building and lower sheds. Around the site are large piles of roots.

Bad Axe’s facility also appears in rail and map references tied to a 1909 Sanborn map entry describing a chicory plant location and linking it to E. B. Muller & Co.

Images on this page may contain affiliate links in which we may receive a commission. See our affiliate disclosure for details.

Historic Photos of Detroit in the 50s, 60s, and 70s

Historic Photos of Detroit in the 50s, 60s, and 70s documents what a Metro Detroiter would have experienced through those decades, from the commonplace to a visit from John F. Kennedy.

What Michigan Chicory is, in Plain Terms

Chicory is a plant with a thick root. When that root is dried and roasted, it takes on a dark color and a bitter-sweet taste. Mixed into coffee, it can add body and stretch the supply.

That “stretch” mattered in an era when coffee prices rose, incomes fell, and households watched every penny. It also mattered because the product could be sold in groceries, packaged for home use, and marketed as a modern improvement to something most people drank every day.

Taken together, these sites show a network of small-town chicory hubs across Michigan during the industry’s peak. Each processing plant – from Capac and Coleman in the Thumb to Pinconning and Linwood in the Bay – worked with nearby farmers. They ground and roasted the plant’s roots on site. Then railroad cars carried the finished chicory blends out to larger markets. By adding these examples, our story now covers the full scope of Michigan’s chicory boom

The 1939 Michigan Production Numbers

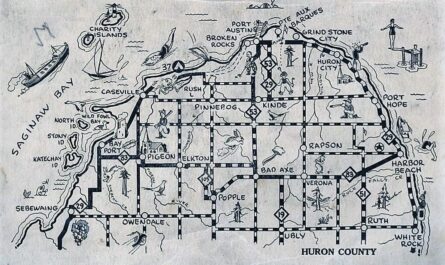

A newspaper story from 1939 gives unusually specific numbers for a farm product most readers rarely think about. Muller and Franck firms handled about 56 million pounds of raw chicory root that year. It also says about 9,000 acres, mostly in the Thumb district, were devoted to chicory planting and harvesting.

We should treat that as period reporting — a snapshot of what the public was told — not a final audit. But it still gives scale.

And it gives geography: the Thumb, Port Huron, and a chain of processing sites. That is not a mom-and-pop process. It’s a system.

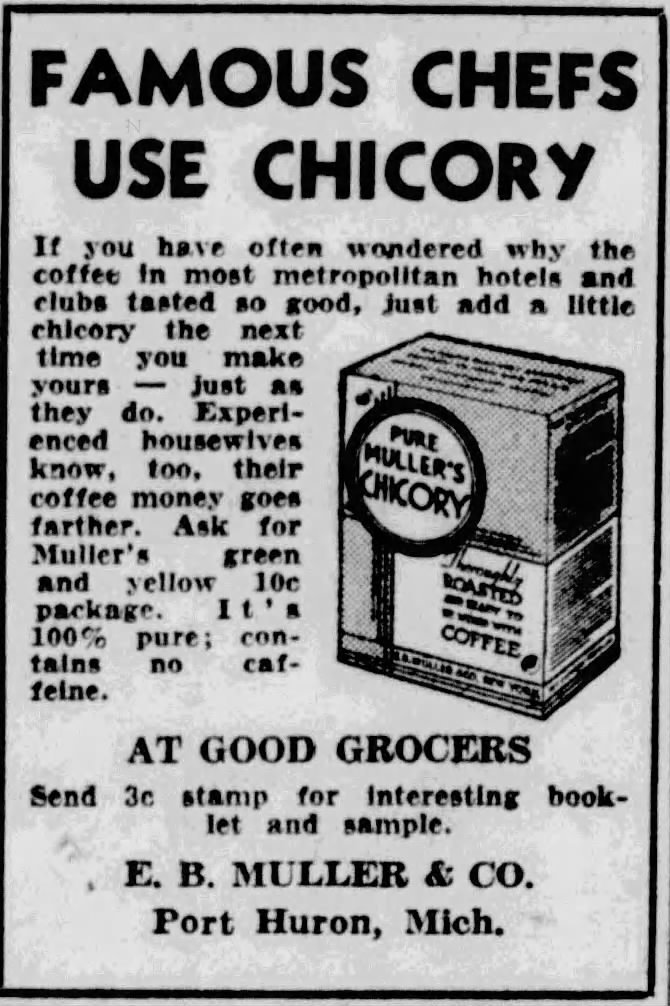

The Companies that Show up on the Labels

Two names appear again and again in Michigan chicory history: E. B. Muller & Co. and Heinr. Franck Sons, Inc. A federal appellate case confirms both firms as manufacturers and sellers of granulated chicory and shows that chicory was large enough to draw federal scrutiny over business practices later on.

Meanwhile, Bay City’s role is backed by a historical marker record for the Franck Chicory Company, tied to the introduction and growth of chicory in Bay County.

Bad Axe is supported by an archival photo record and a rail-site summary tying the facility to E. B. Muller & Co.

Advertising Tells How Chicory Was Used

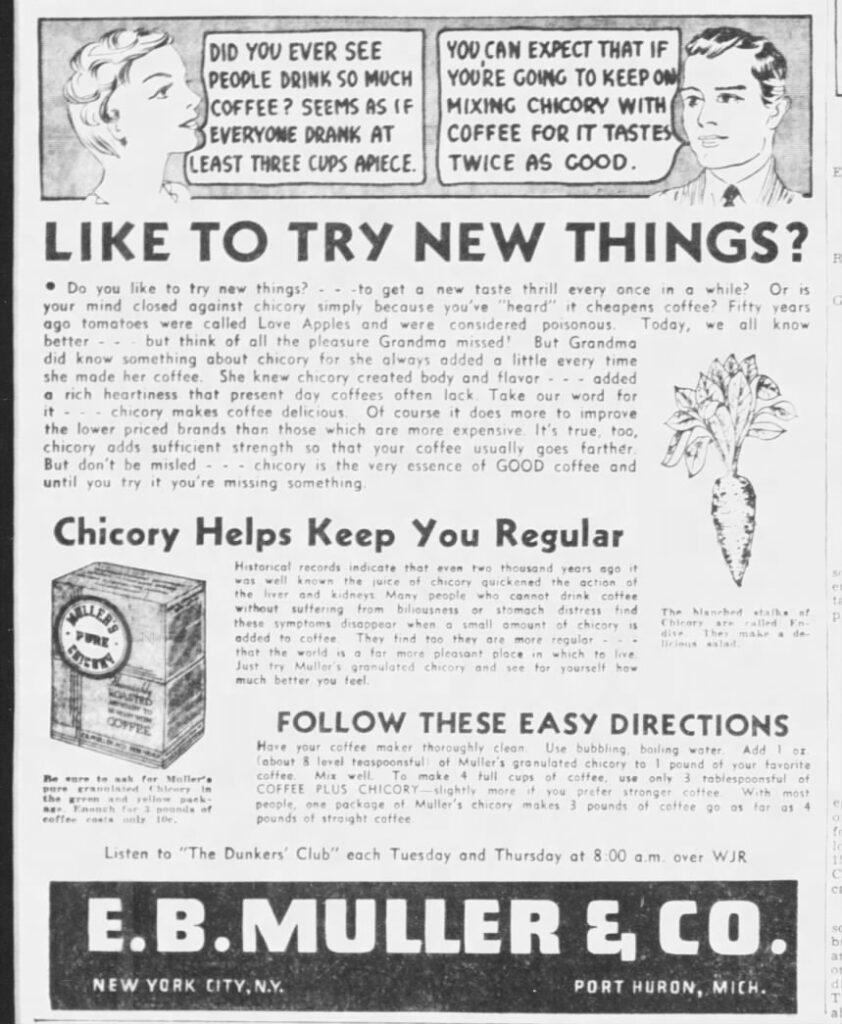

Chicory advertising in the early 20th century did not focus on novelty. It focused on routine, marriage, and domestic order. One widely circulated newspaper advertisement from E. B. Muller & Co. framed chicory as part of a successful household, not a specialty product.

One ad reads: “Famous Chefs Use Chicory.” It pushes “Pure Muller’s Chicory” and tells shoppers to buy it “at good grocers.” It prints E. B. Muller & Co., Port Huron, Mich., at the bottom.

Another ad uses a different tone. It asks readers if they like to try new things, then argues that chicory is not new at all. It claims mixing chicory with coffee makes it taste “twice as good” and helps coffee go farther.

The ad also leans on authority. It urges listeners to tune in to “The Dunkers’ Club” radio program on WJR, linking chicory to modern media and expert voices. This was a way to build trust in an era when radio carried weight in American homes.

There’s also a health-style claim: “Chicory Helps Keep You Regular.” That is an advertising line, not medical proof. But it does show what the company believed would move product: not just taste, but a promise of usefulness.

The copy avoids technical detail. Instead, it stresses taste, appearance, and habit. Readers are told that adding chicory improves flavor, deepens color, and makes coffee “easier to digest.” These claims are not supported by evidence in the ad, but they reflect how food products were marketed at the time—through reassurance rather than proof.

Another theme is economy. The ad promises that coffee “goes farther” when chicory is added. Instructions show exact measurements, treating chicory as a normal pantry item rather than a substitute of last resort. The product is framed as practical, not inferior.

Why Mid-Michigan & Thumb Were Ideal For Michigan Chicory

Chicory’s Michigan story is hard to separate from two older Michigan realities:

- Root-crop farming was already normal in this region. Sugar beets were already part of the farm’s crop rotation, seasonal labor, and delivery-to-factory contracts. Bay County histories describe how new agricultural industries changed farm finances and seasonal employment patterns in the early 1900s.

- Rail lines turned bulky crops into cash crops. A root is heavy. It spoils. It costs money to move. A rail siding next to a drying plant changes the math.

Bad Axe’s postcard shows the railroad connection in one image. Port Huron’s brand labels show the packaging and sales side. Bay City’s marker record shows the processing footprint. Put together, they sketch an entire supply chain.

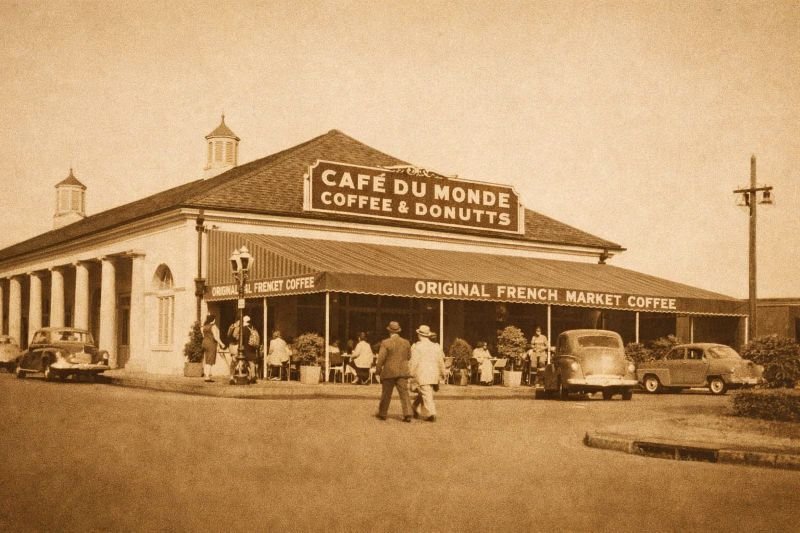

The Lesser-known Michigan Chicory Link to New Orleans

Federal records establish that R.E. Schanzer, Inc. was a New Orleans–based firm operating in the U.S. chicory industry by about 1930. Court and Federal Trade Commission documents state that, during this period, all domestically grown chicory in the United States was produced in Michigan and raised under contract with Michigan farmers. Schanzer operated as a competitor to established firms such as E. B. Muller & Co. and Heinr. Franck Sons, Inc., is relying on the same Michigan-grown supply chain. No verified source confirms an exact opening date for a Schanzer-owned plant in Linwood or the year Schanzer began contracting with farmers there.

The same federal court findings document that approximately 75 percent of all chicory sold in the United States was consumed in the New Orleans trade area, which included much of the South. This concentration of demand explains the direct economic link between Michigan production and New Orleans consumption. Michigan supplied the crop through contracted farming and rail-connected processing plants, while New Orleans functioned as the primary domestic market for chicory used in coffee blends.