Along the Lake Huron shoreline in Michigan’s Thumb, White Rock is easy to miss if you drive through too fast. Today it feels quiet. But the History of White Rock, Michigan is not a quiet story. It is a story about a place that mattered first as a landmark, then as a village, then as a shoreline getaway—and finally as a memory kept alive by photographs, a schoolhouse, and a name written into federal treaty language.

White Rock’s most lasting influence may not have been as a resort or a town at all. It may have been as a point on a map—used to define where other people said the lines would go.

Video – History of White Rock – A Tiny Viollage with Big-Map Energy

A Landmark Before a Village

Before there was a “Village of White Rock” in everyday talk, the shoreline here was part of older travel routes and seasonal cycles. Long before Michigan became a state, the Great Lakes were a working world—canoe routes, fishing grounds, trade corridors, and family places that changed with the seasons.

When U.S. officials described land in treaties, they often relied on physical points people could recognize—rivers, bays, and distinct shoreline markers. In 1807, one such agreement, commonly known as the Treaty of Detroit, used “White Rock” as a named reference point while describing boundaries and cessions involving Odawa (Ottawa), Ojibwe (Chippewa), Potawatomi, and Wyandot nations.

That matters because it tells you something basic: “White Rock” was not just a later marketing name. It was already a known marker—important enough to appear in federal treaty language at the start of the 19th century.

A modern tribal timeline can help frame what those treaty years meant on the ground: land cessions, pressure to relocate, and a sharp imbalance of power that left long shadows over many Michigan shore communities.

A Village Takes Shape on the Lake

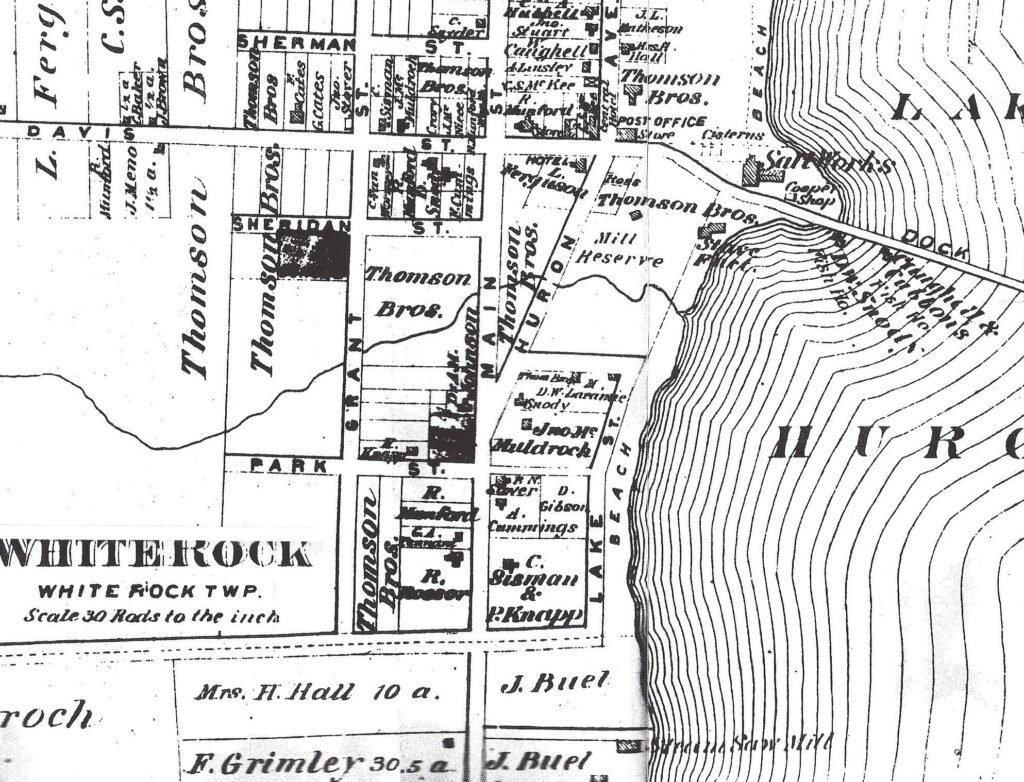

By the late 1800s, the Thumb’s shoreline communities were developing into working settlements and seasonal stops. The plat-era map of White Rock shows an organized shoreline village plan: streets, lots, and named property owners. It reads like a statement of intent—people expected the village to grow.

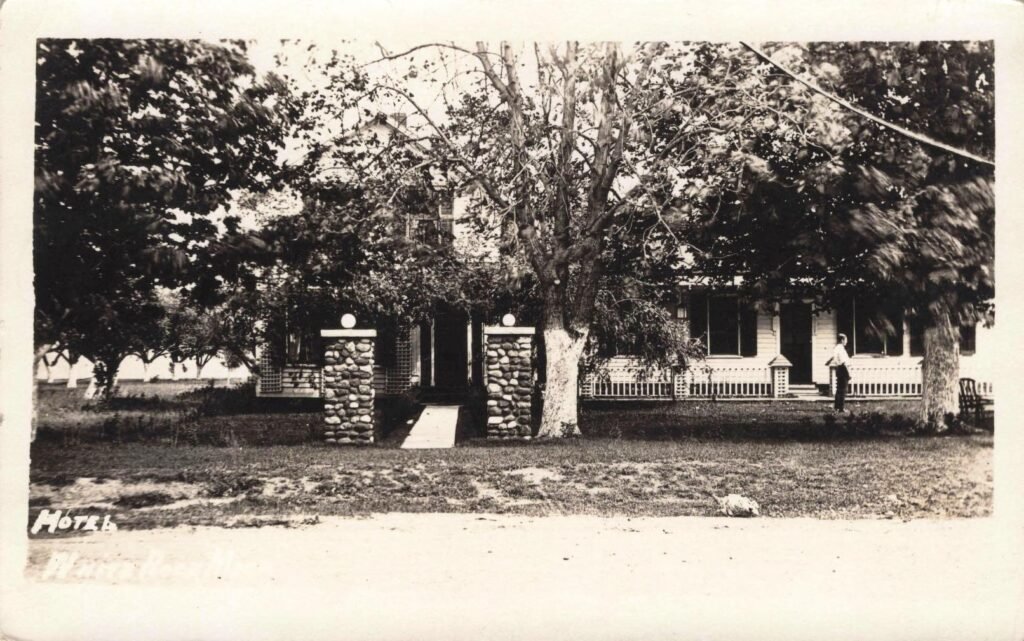

Not every lake village becomes a town with factories and rows of brick storefronts. Some places grow in a different direction. White Rock leaned into the shoreline itself. Summer visitors mattered. A hotel mattered. A dance hall mattered.

And we know that because real-photo postcards captured it.

In the early 1900s, postcards were not just souvenirs. They were social media of their day—proof you went somewhere, proof you saw something, proof that a place was “real.” The University of Michigan’s digital postcard project explains how large the real-photo postcard series is and how it was described through public tagging and metadata work.

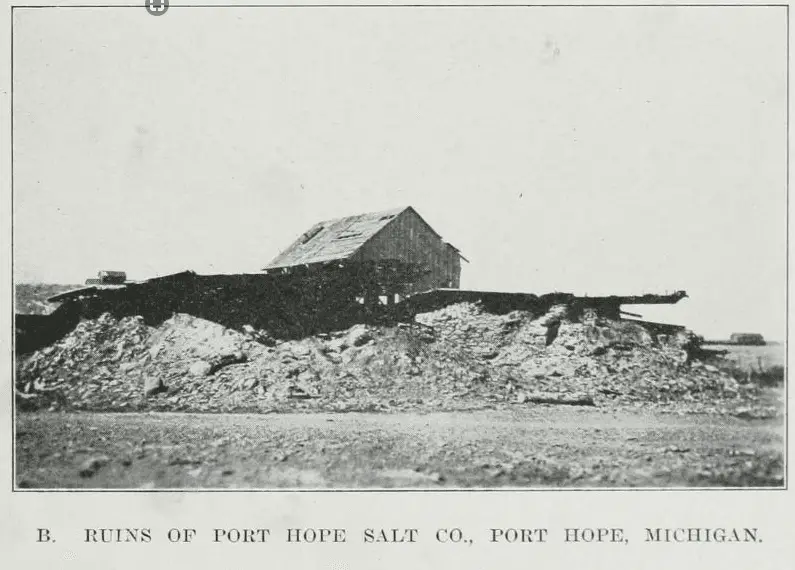

Salt Wells Spell Opportunity for White Rock

An April 29, 1873, item in The Times Herald of Port Huron reported that a salt well sunk at White Rock in Huron County had produced brine described as “of the best quality,” stirring talk of a major Lake Huron shoreline salt trade. The paper said a Port Huron effort was forming to bore for salt, and noted industry chatter that a prominent lumber firm would soon begin drilling. Citing the Lumberman’s Gazette, the story described the White Rock well as about 703 feet deep and claimed its brine tested stronger and cleaner than typical Saginaw brine, meaning less evaporation to make a barrel of salt.

Fire, Rebuilding, and the Long Middle Years

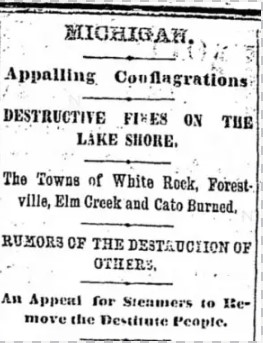

Local historical reporting on White Rock often returns to a blunt turning point: fire.

According to a Huron County historical summary circulated through local history writing, the original village was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1871 and rebuilt afterward.

That claim fits the broader regional pattern of major fires in the Thumb and nearby areas in the late 1800s. But the key point for a White Rock story is simpler: the village did not move forward in a straight line. It was interrupted. It had to start again.

Rebuilding does not always mean getting bigger. Sometimes it means getting by.

The Ball Room: A Shoreline Stage

The most dramatic image in this set is also the most telling.

A ballroom on the Lake Huron shore tells you what White Rock was selling: an experience. It was not just a stop on a map. It was a place where people came to be entertained.

The postcard does not tell us what the band played or who paid at the door. But it does show the basic truth of the resort era: the village expected visitors, and it built for them.

Here is the hard question that hangs over many Michigan resort histories: who benefited, and who was pushed out of the picture?

When a place becomes a leisure destination, the story can narrow. It can skip over the older shoreline uses, the treaty realities, and the Native presence that predates the village name itself. The History of White Rock, Michigan, is stronger when it refuses to do that.

The Schoolhouse That Outlasted the Resort

Resorts rise and fall. Public buildings often carry the longer story.

A key surviving piece of White Rock’s civic life is the White Rock School. Local historical documentation describes the building as constructed in 1909, serving students for decades, and then closing in 1968. It later became part of the Huron County Historical Society’s work to preserve local history.

This is where the village story becomes personal. If you grew up in rural Michigan, you know what a one-room school meant. It was not just a building. It was a community statement: we are here, and our kids will learn here.

When schools close, it is often because population shifts, roads change, and jobs move. The closure does not mean the place stops mattering. It means the center of gravity moved.

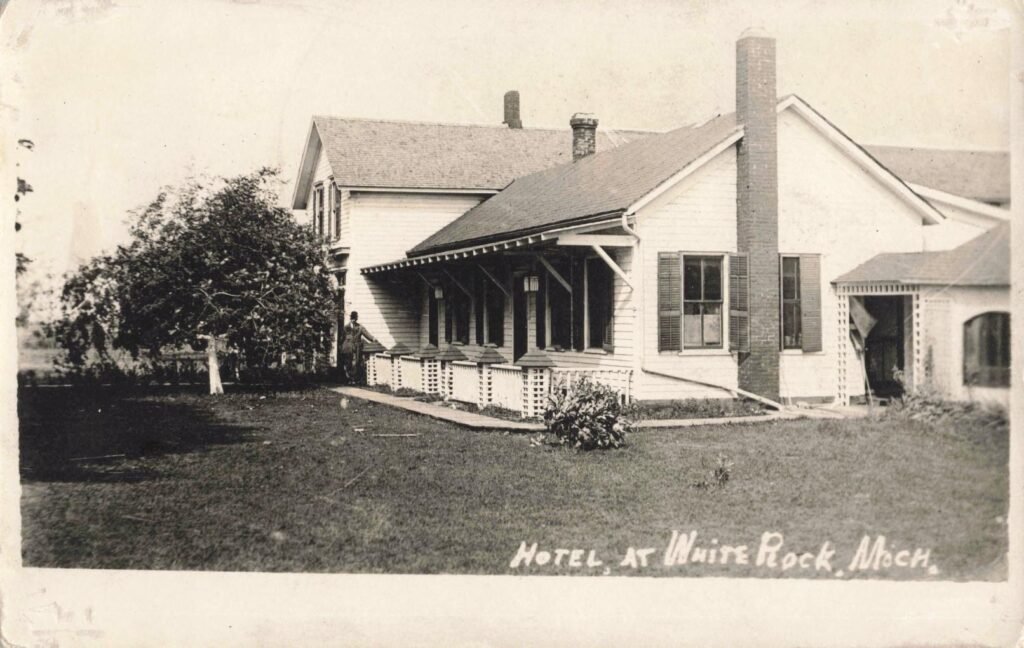

A Home Scene: Ordinary Life in the Village

Resort postcards show the public face. Another image shows something quieter.

This kind of photo matters because it corrects the postcard version of history. A village is not only its hotel and its dance hall. It is also laundry, fences, gardens, mud, wind, and long winters when the lake looks like a sheet of iron.

What White Rock Means Now

White Rock today sits in the category many Michigan places fall into: a named location that once carried more infrastructure than it does now. That does not make it “gone.” It makes it a different kind of place—a place you interpret through fragments.

Those fragments include:

- Treaty language that names White Rock as a boundary marker.

- Local history accounts describing destruction and rebuilding after the 1871 fire.

- A preserved school story that ties the village to families and public life.

- Photographs and postcards that show the hotel, the ballroom, and the lived-in spaces in between.

And above all, it includes the older truth that the shoreline mattered to Native nations long before survey lines and resort fences. If you want a well-rounded telling of the History of White Rock, Michigan, that has to stay in the frame.

Sources for the History of White Rock Michigan

“Treaty of Detroit (1807).” Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties, Oklahoma State University Library, accessed 13 Dec. 2025.

“Treaties, Conventions, International Acts, Protocols and Agreements Between the United States of America and Other Powers, 1776–1909 (7 Stat. 104–107).” govinfo, U.S. Government Publishing Office, accessed 13 Dec. 2025.

“Treaty with the Ottawa, Etc. (Treaty of Detroit), 1807.” Michiganology, Library of Michigan, accessed 13 Dec. 2025.

“Huron Band History.” Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi, accessed 13 Dec. 2025.

Rathbun, Scott. “Our Towns: White Rock.” The Michigan Thumb, accessed 13 Dec. 2025.

“White Rock School Museum.” Michigan History Trail, accessed 13 Dec. 2025.

“About the Collection.” David V. Tinder Collection of Michigan Photography, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan Library Digital Collections, accessed 13 Dec. 2025.

“David V. Tinder Collection of Michigan Photography, ca. 1845–2000.” Finding Aids, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan, accessed 13 Dec. 2025.

“David V. Tinder Collection of Michigan Photography.” William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan, accessed 13 Dec. 2025.

“Native American Treaties.” National Archives, accessed 13 Dec. 2025.