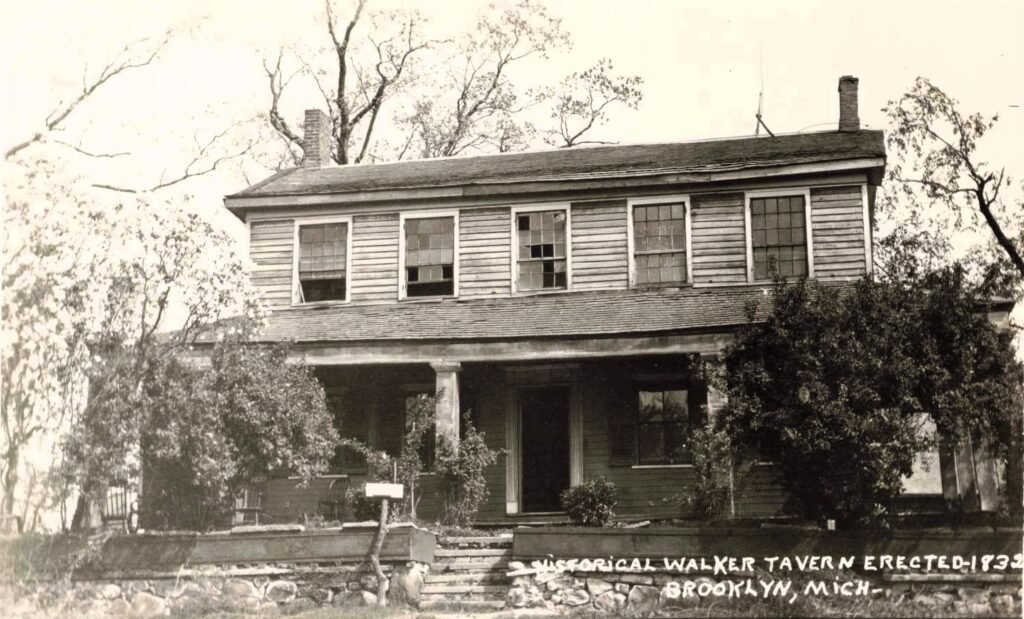

At the corner of U.S. 12 and M-50 in Michigan’s Irish Hills, the Walker Tavern sits above the road on a small bluff. The Michigan History Center dates the white clapboard building to about 1832. Long before the area became a casual weekend drive, this spot mattered because the route that became U.S. 12 was a key line of travel between Detroit and Chicago.

The history of the Walker Tavern is not just a story about one stagecoach stop. It’s a story about the ancient trail that became the Chicago road, the people who used it, and the way Michigan later turned that travel history into a visitor attraction.

Table of Contents for the History of the Walker Tavern

Video – History of The Walker Tavern at Cambridge Junction: Michigan’s 1832 Stagecoach Stop

A tavern built for traffic, not fame

The Walker Tavern was built at a junction. That matters. Roads concentrate people, and people create business. In the early 1800s, a tavern could be part inn, part meal stop, part message center. Travelers could learn what the next stretch looked like—mud, snow, broken bridges, or a safer route.

Origins and Early Stagecoach Era (1832–1842)

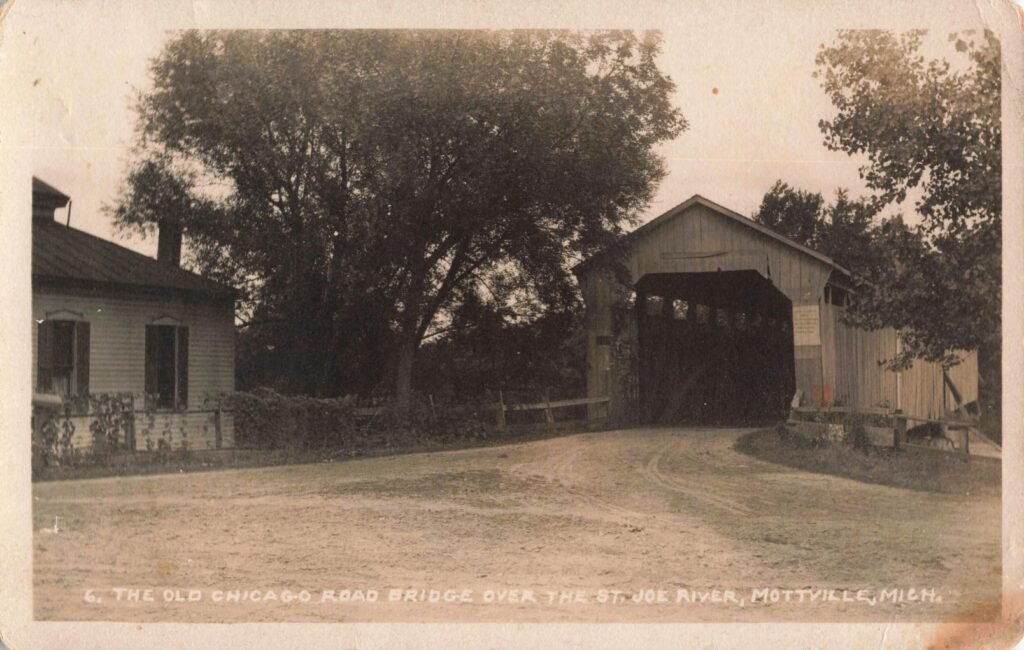

A modest one-and-a-half-story wooden farmhouse is built at Cambridge Junction (the crossing of the Monroe Pike and Old Chicago Road) in Michigan’s Irish Hills. Perched by the old Great Sauk Trail (later U.S. 12, the Detroit–Chicago route), this site quickly becomes an ideal stopover for westbound pioneers. By the mid-1830s, Calvin Snell is operating the house as a tavern (known as “Snell’s Tavern” by 1836) to serve travelers. The grueling stagecoach trip between Detroit and Chicago took about five days, and Snell’s tavern offered weary passengers meals, rest, and overnight lodging along the way.

The Early Tavern Became a Public Gathering Point

Even in its early years, the tavern doubles as a civic center for the sparsely settled area. Locals and travelers gather here to exchange news and mail – the tavern served as a post office where residents picked up letters in the era before home delivery. The inn also hosts political meetings and even church services, with circuit-riding preachers holding Sunday worship in the tavern’s common room. This mix of roles made the junction a lively social hub on the frontier. (Notably, famous figures like statesman Daniel Webster and novelist James Fenimore Cooper were reported to have stopped at the tavern during this period.)

The Michigan History Center notes the tavern originally sat only a short distance from an older trail, later tied to the corridor that became U.S. 12. This framing helps explain why the site existed at all: it stood where movement already happened.

Sylvester Walker’s Ownership and Expansion (1843–1860)

In 1842–43, Sylvester Walker and his wife Lucy purchase Snell’s establishment and rename it “Walker Tavern.” The Walkers – experienced innkeepers from New York – convert the former farmhouse into a full-fledged tavern and inn. Under their proprietorship, Walker Tavern thrives as a major stagecoach stop. Two stage lines run daily through Cambridge Junction, and on a busy evening 10–20 wagons might line the yard awaiting food and lodging.

The tavern’s barroom and porches ring with activity: locals debate politics, travelers swap stories, and itinerant ministers occasionally lead religious gatherings on the premises. The tavern gained a reputation for hospitality – as one stage driver recalled, men of all classes would “stretch out their day’s drive to reach the hospitable roof of the Walker’s hotel,” where crowds of 50+ people might assemble to hear news and collect mail amid boisterous cheer. Walker Tavern by the 1840s was both a transportation crossroads and a focal point of community life in the Irish Hills.

1853–1854 – Construction of the Brick Tavern

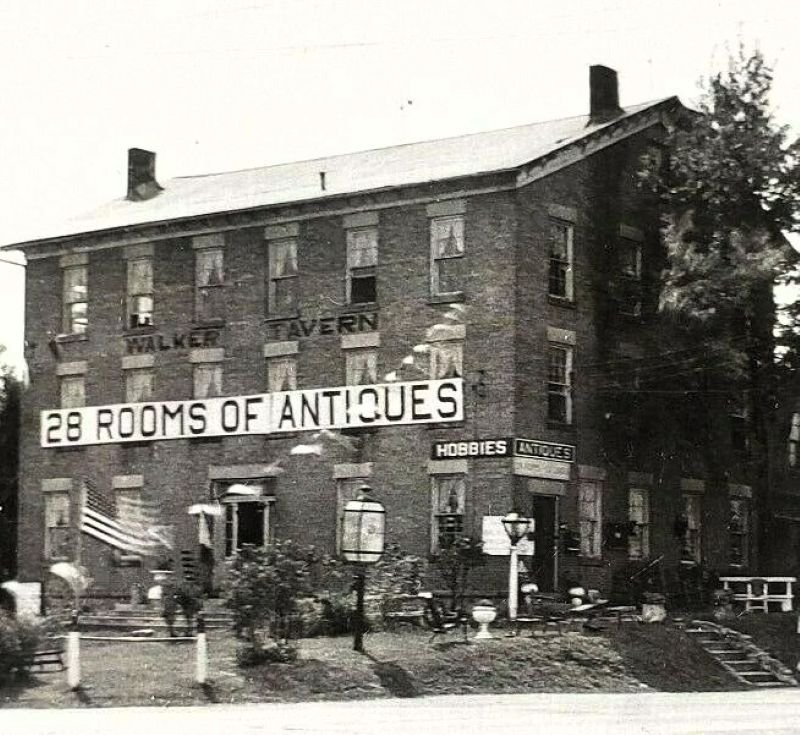

Now look across the highway. We see a tall brick structure marked “ANTIQUES,” and another exterior view that frames both buildings in the same scene.

Business at Walker Tavern boomed through the 1840s, prompting Sylvester Walker to expand. In 1853 he commenced building a large three-story brick hotel directly across the road from the original tavern. Completed by late 1853 or early 1854, “S. Walker’s Hotel” (now known as the Brick Walker Tavern) was an unusually substantial inn for its time: a red-brick structure featuring a dedicated dining room and taproom on the first floor, private guest bedrooms on the second, and a spacious third-floor ballroom for dances and public events.

This made it one of Michigan’s only three-story hotels of the era, offering more refined accommodations than the old log and frame taverns. Once the new Brick Tavern opened, Sylvester and Lucy Walker used the original 1832 tavern as their private home (while still serving travelers in the new hotel). A historical marker notes that after 1854 the smaller frame tavern essentially became the Walker family residence.

The brick building signals a different level of travel business—larger, taller, built for more guests. Paired with the earlier white tavern, it shows how the junction adapted to changing traffic. First the stage era. Then expanded lodging. Then the car-tourism era that sold labeled rooms and staged scenes.

This is the Brick Walker Tavern, also known as S. Walker’s Hotel. It is listed on the National Register of Historic Places (ref. 07000381, listed May 2, 2007).

Post-Stagecoach Transitions (1860s–1910s)

After Sylvester Walker’s time, the two tavern buildings followed different paths:

Brick Walker Tavern

This property saw rapid turnover during and after the Civil War. In 1863 Giles sold the brick inn to William Graves and George Curtis, who that same year sold it onward to Lyman Nearing. Nearing, an entrepreneur from New York, moved in with his wife Jane and by 1865 had rebranded the hotel as the “Nearing House.” The Nearings ran the establishment for over two decades. The brick Junction Hotel (as it was also called) continued serving travelers and local functions during this time – its ballroom hosted community dances, and its bar and guest rooms catered to regional traffic.

However, the decline of stagecoach travel made business challenging. In 1887, Lyman Nearing lost the property (the mortgage was foreclosed) and the hotel changed hands again. Late 19th-century owners included a proprietor named Culver (giving rise to the name “Culver’s Hotel”) and others, with the place sometimes simply called the “Junction House.” Despite these changes, the Brick Tavern remained a recognizable landmark at US-12 and M-50– a three-story reminder of the stagecoach days, even as it functioned sporadically as a local hotel, boarding house, or private residence through the turn of the century.

Original Walker Tavern (Frame House):

In 1865, following Sylvester Walker’s death, Lucy Walker sold the old 1832 tavern and farm to Francis Asbury Dewey. Dewey had been a stagecoach driver on the Chicago Road and was intimately familiar with the tavern’s legacy. Under the Dewey family, the former inn ceased operation as a public tavern and became a farm homestead. Francis A. Dewey and his descendants lived in the old tavern-house and worked the surrounding land for over 50 years (three generations).

During this period, Francis meticulously preserved the tavern’s early records and history, recognizing its historic significance. However, he never managed to make it a profitable inn again – the railroad had overtaken the highway, and the building served mainly as the Dewey family’s private residence and farm center. By the early 20th century (circa 1920), the property – still owned by the Dewey heirs (great-nephew Wilford C. Dewey) – was aging and little-used, essentially an old relic of pioneer days awaiting new purpose.

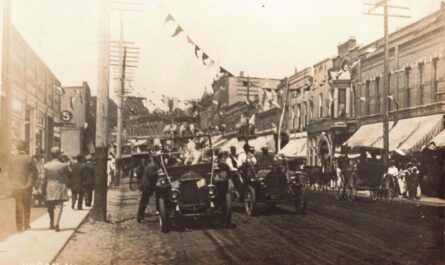

Old Chicago Road and the Irish Hills corridor

Modern drivers know U.S. 12 as a state highway that cuts through southern Michigan. In the 1800s, this corridor helped connect Michigan’s older population centers with settlements farther west. People traveled for work, family, trade, and land. A tavern stop was not a luxury. It was part of the trip plan.

Stagecoach Heyday Wanes

In the late 1850s, the stagecoach era gave way to the rail era. New railroad lines began bypassing Cambridge Junction, diverting long-distance travel away. Even so, Walker kept the business going; local patronage remained strong, with the Brick Tavern’s taproom popular among area residents, and community balls continuing in the grand ballroom. Sylvester Walker himself operated the taverns until about 1853–54 (opening the brick hotel), and he continued overseeing the property through the 1850s. By 1859, with travel patterns shifting, Walker decided to step back: he sold the Brick Tavern in that year to Silas S. Giles, a new proprietor, though Sylvester reportedly continued living on-site at the brick hotel until his death a few years later.

Today, the site is part of a state historic park. The Michigan DNR frames the property as an asset to tourism in the Irish Hills, and the Michigan History Center notes state operation beginning in 1965.

Images on this page may contain affiliate links in which we may receive a commission. See our affiliate disclosure for details.

Historic Photos of Detroit in the 50s, 60s, and 70s

Historic Photos of Detroit in the 50s, 60s, and 70s documents what a Metro Detroiter would have experienced through those decades, from the commonplace to a visit from John F. Kennedy.

Historically Wheting Your Whistle in The Tap Room

By the early 1900s, travelers were changing. Cars brought new visitors, new expectations, and new competition among roadside stops. The Walker Tavern entered an era when history could be presented as entertainment.

The tap room photo reads like a set. It signals that the Walker Tavern was not only a preserved building, but also an interpreted experience. This matters because it shows how early tourism shaped what visitors were told to notice.

Roadside Revival – The Irish Hills Tourism Boom (1920s)

The 1910s–1920s brought the automobile and a second life for Walker Tavern. The historic Chicago Road was incorporated into the new U.S. Highway system and by the mid-1920s was known as U.S. Route 112 (today’s US-12). In 1924–26 the highway was fully paved, dramatically increasing tourist travel through the Irish Hills region. Southeast Michigan’s Irish Hills, with its chain of lakes and scenic knolls (about 75 miles from Detroit), became a hugely popular getaway – thousands of city dwellers would take day-trips and weekend drives to this area.

Cambridge Junction, situated at the intersection of US-112 and M-50 amid the Irish Hills attractions, was perfectly positioned to capitalize on the new auto tourism traffic. Early roadside enterprises sprang up: notably, in 1924 two 60-foot observation towers were built on rival hillsides near Walker Tavern (the famous “Irish Hills Twin Towers”), each accompanied by a gift shop, restaurant, small hotel and gas station along then–US 112. The era of roadside Americana had begun, and the stage was set for Walker Tavern to transform from a forgotten relic into a tourist draw.

1921–1922 – Hewitt Purchases Walker Tavern

With the Dewey family ready to sell the historic tavern, an enthusiastic buyer emerged. In November 1921, the property (including both the old frame tavern and surrounding acreage) was purchased by Rev. Frederick Hewitt, an Episcopalian minister and avid collector of antiques. Hewitt was a long-time friend of Henry Ford and shared Ford’s passion for preserving Americana.

Seeing Walker Tavern’s potential as a heritage attraction, Hewitt immediately set about restoring the building and curating artifacts for display. He formally opened the old tavern as a museum on May 30, 1922 (Memorial Day), charging a small admission for visitors to tour its rooms filled with pioneer-era antiques. That same year, the site’s significance was officially recognized by the Daughters of the American Revolution, who placed a commemorative historical plaque on the tavern in 1922. Under Hewitt’s care, Walker Tavern became one of Michigan’s earliest private museums – “a valuable monument” to the past, as one contemporary noted.

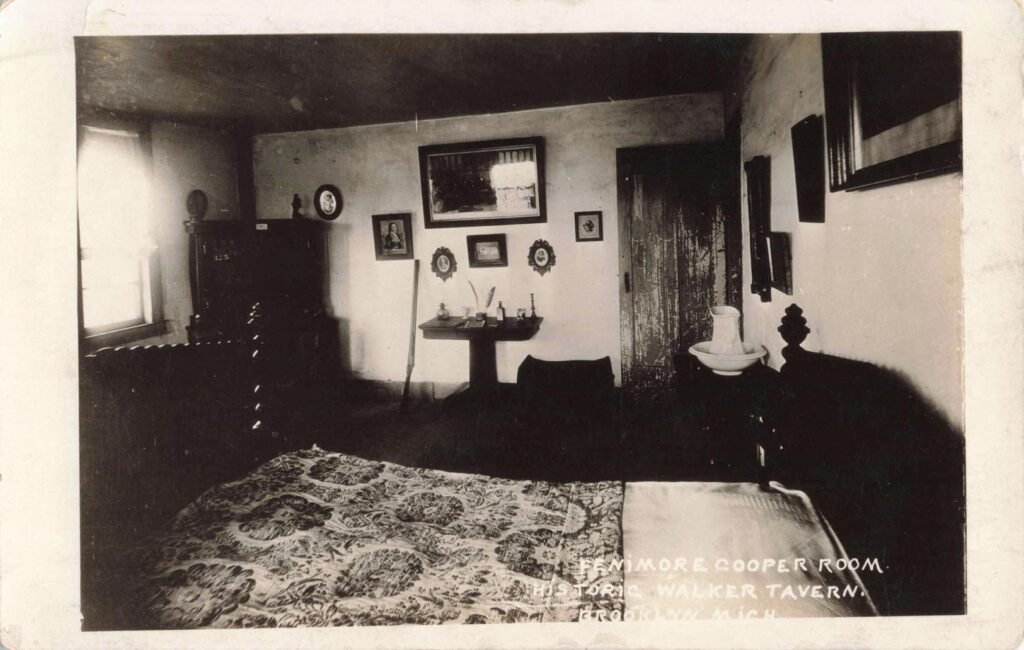

The “Fenimore Cooper Room” and named stories

One of your interior photos is labeled the “Fenimore Cooper Room.” The room itself is plain: a bed, a wash basin, and wall pictures that suggest a curated period look.

Without a primary record, the careful approach is to treat this label as a tourism-era name, not proof of a specific stay. It still tells us something real: the site used named rooms and famous associations as part of its public draw.

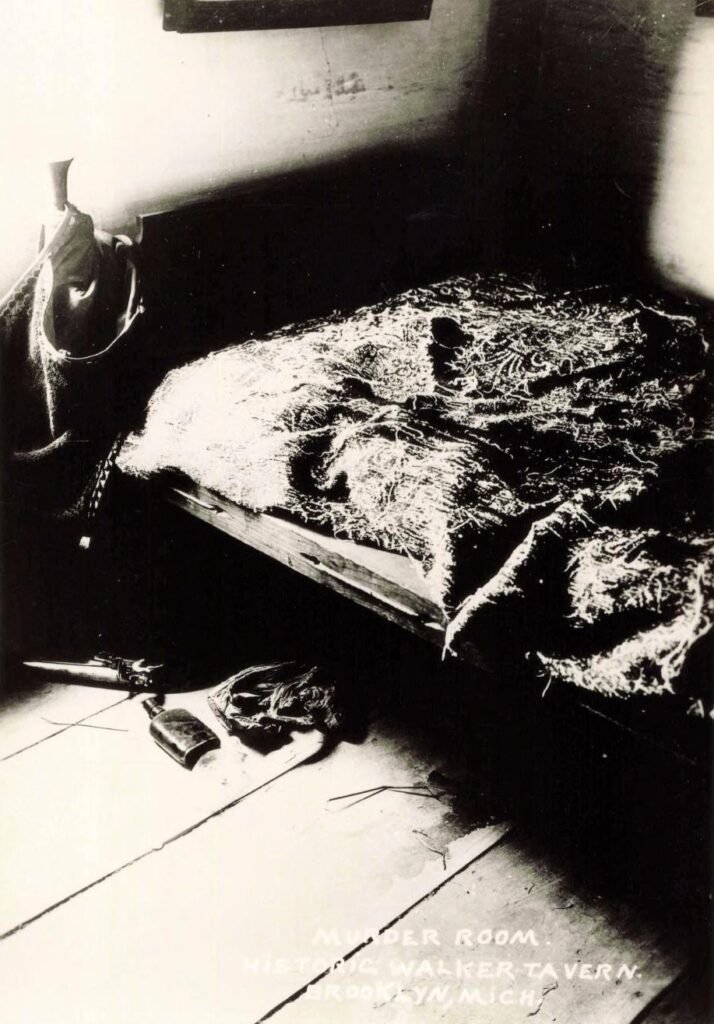

What the “Murder Room” photo is actually about

Our most pointed question was about the “Murder Room” image. Here is the clean answer:

It’s a promotional room label used in the Walker Tavern’s tourist pitch. A Detroit Public Library digital record preserves a postcard image of the “Murder Room” and includes the printed text from the back. That text advertises “46 thrilling rooms” and sells “history, drama, murder,” along with antiques for sale, at the corner of U.S. 112 and M-50.

This evidence confirms the “Murder Room” was part of how the site was presented to visitors. It does not confirm that a murder happened. If a verified incident exists, it should appear in a contemporaneous newspaper report, court record, or other primary source tied to a date and a named person. The postcard alone is not that.

Costumed guides and the rise of interpreted history

In the mid 1900s we find a photo showing “Guides at Walker Tavern,” posed in costume near a porch.

This is another sign that Walker Tavern was used as an experience, not only a building. Visitors came to see a version of the past shaped for them. That approach is common now. What’s surprising is how early it appears here.

Why this site matters in Michigan history

History of The Walker Tavern at Cambridge Junction Michigan is not just about an 1830s structure. It’s about a travel corridor that stayed important for generations. It’s also about the way Michigan’s roadside culture shaped public memory.

The “Murder Room” and other dramatic labels are not just trivia. They are evidence of how Michigan sold “the past” to early motorists—long before modern museums perfected the formula.

Today, the state park presents Walker Tavern within an 1840s–1850s lens, while the site’s own tourism-era artifacts—like postcards—quietly document another layer of history: the history of historical marketing.