When most people think of Michigan’s auto industry, they jump straight to GM, Ford, and Chrysler. But for much of the 20th century, the state was crowded with independent manufacturers trying to carve out their own space. Some pushed engineering in new directions. Others tried to build full-line rivals to the “Big Three.” All of them are gone. This is the story of defunct Michigan automakers in the 1900s.

Defunct Michigan Automakers – Table of Contents

Video – Michigan’s Long Gone Car Companies

Michigan’s Defunct Automakers

This section looks at several of the best-known independent automakers that were headquartered in Michigan and no longer exist as carmakers. Each one left a mark on engineering, design, or car culture before money, mergers, or macroeconomics caught up with them. These defunct Michigan automakers each contributed to engineering, production methods and unique styling that helped Michigan become the auto capital of the world.

Packard: Detroit’s luxury benchmark that ran out of road

Packard Motors started building cars in 1899 and moved its operations to Detroit in 1903. For decades, Packard was one of America’s premier luxury brands, competing directly with Cadillac and Lincoln. The massive East Grand Boulevard plant, designed by Albert Kahn, became a symbol of early Detroit industry.

What Packard was famous for:

Packard built quiet, smooth, and highly engineered luxury cars. Its straight-eight engines, refined chassis, and upscale interiors gave it a strong appeal among wealthy buyers. By the 1930s, “Ask the man who owns one” was more than a slogan; it reflected respectable reliability and status.

What led to Packards demise:

Packard struggled after World War II. Styling updates were slow. The company was late to adopt a modern V-8 and competitive automatic transmission. In 1954, Packard acquired the failing Studebaker, expecting economies of scale; instead it inherited deep financial problems. The combined company was under-capitalized and could not match the Big Three in yearly model changes and advertising. Production in Detroit ended in 1957, and the last Packard-badged cars, built in South Bend on Studebaker platforms, rolled out in 1958.

Packard’s story is a straightforward example of what happens when a high-end brand cannot keep up with rapid postwar change and far larger rivals.

Hudson: Step-down innovation without the balance sheet

Hudson Motor Car Company launched in Detroit in 1909 and became known as a serious engineering house. Its most famous achievement was the 1948 “step-down” body, which located the passenger compartment between the frame rails rather than on top of them. The design lowered the center of gravity and improved handling years before “sport sedan” became a marketing phrase.

What Hudson was famous for:

Hudson’s low-slung step-down cars and the “Fabulous Hudson Hornet” made a name in NASCAR and stock-car racing in the early 1950s. The Hornet’s big inline-six engine and strong chassis dominated tracks and built real performance credibility.

What led to Hudson’s demise:

Sales shrank in the early 1950s, and Hudson spent heavily on the compact Jet, which flopped in the market. By 1954, losses forced a merger with Nash-Kelvinator, creating American Motors Corporation. Hudson-badged cars were built on Nash platforms until 1957, when the name was dropped to focus resources on the Rambler line. The company didn’t die overnight; it faded as the badge lost support inside AMC.

American Motors: the last independent swallowed for Jeep

American Motors Corporation (AMC) was technically a merger of independents—Hudson and Nash—with headquarters eventually in Southfield, Michigan. Formed in 1954, AMC became known as “the last independent automaker” in the U.S.

What AMC was famous for:

AMC excelled at niche vehicles: Rambler compacts, the AMC Eagle all-wheel-drive passenger car, and distinctive models like the Gremlin, Pacer, and Javelin. Its designers, working with smaller budgets than the Big Three, often reused components in creative ways and chased market segments the giants largely ignored.

What led to AMCs demise:

AMC survived longer than most independents but never had the capital to compete head-to-head. The company turned to Renault for investment in the late 1970s. By the mid-1980s, financial pressure and weak U.S. sales made AMC a takeover target. Chrysler acquired AMC in 1987, largely to get Jeep and a modern assembly plant. AMC was folded into Chrysler by 1990, leaving Jeep as the most visible remnant.

REO: Ransom Olds’ second act in Lansing

REO Motor Car Company, founded by Ransom E. Olds in Lansing in 1905, was his follow-up after leaving Oldsmobile. REO built both cars and trucks and quickly gained a reputation for durable commercial vehicles.

What REO was famous for:

The REO Speed Wagon, introduced in the 1910s, became one of the best-known early light trucks. It helped set expectations for purpose-built commercial chassis instead of modified passenger cars.

What led to REOs demise:

Passenger car production ended in 1936 after years of weak demand during the Great Depression. REO shifted to trucks, but postwar competition from larger truck makers and ongoing financial trouble led to repeated reorganizations. Vehicle manufacturing operations were sold off in the 1950s, and REO’s truck operations were eventually merged into Diamond Reo, which also disappeared. By the late 1960s, the original REO entity was gone from vehicle production. Wikipedia+1

REO’s story shows the limits of staying in smaller-volume commercial niches once national fleets and big orders favored large manufacturers.

Durant Motors: Lansing’s failed “second GM”

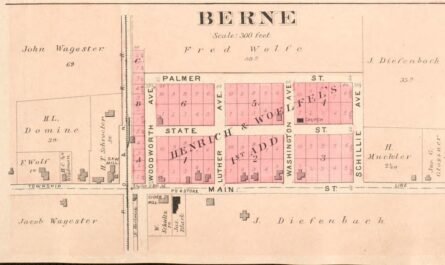

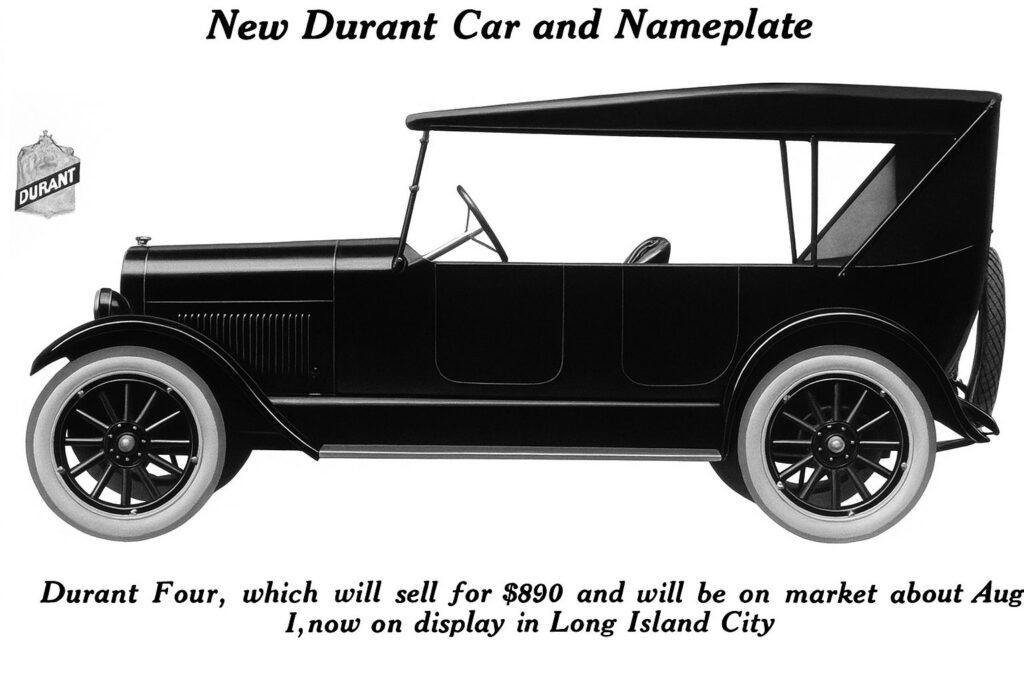

Billy Durant, the founder pushed out of General Motors—twice—tried to build a rival empire with Durant Motors in the 1920s. The company assembled several brands under one corporate umbrella, and Lansing became a major production site.

What Durant Motors was famous for:

Durant Motors tried to copy GM’s multi-brand strategy: Durant, Star, Flint, and others targeted different price levels. For a brief period, the firm looked like it might grow into a fourth national carmaker.

What led to Durants demise:

Sales never reached the volume needed to support so many brands and factories. By the early 1930s, the company was losing dealers and market share. The 1929 stock market crash and Great Depression hit just as Durant Motors was overextended. Production in Lansing ended in August 1931; Canadian operations lasted only slightly longer.

Durant’s attempt underlines how hard it was—even in the boom 1920s—to stand up a full-line competitor without deep and steady capital.

Hupmobile: Detroit’s early everyman car that moved up too far

The Hupp Motor Car Company of Detroit started building Hupmobiles in 1909. Early models were simple, affordable cars aimed at the same buyers Ford was targeting. Hupmobile quickly earned a reputation for durability and good value.

What Hupmobile was famous for:

A 1910 Hupmobile was the first police car used by the Detroit Police Department. The company also experimented early with all-steel bodies and introduced features such as “free wheeling” and fresh-air heaters in the 1930s.

What led to Hubmobiles demise:

Management tried to move Hupmobile upmarket, dropping smaller, cheaper cars and introducing more expensive eight-cylinder models. That shift collided with the Great Depression. Sales fell sharply after 1929, and the company piled up debt. In a last attempt to revive interest, Hupmobile bought the dies for the striking Cord 810 body and reworked it into the Hupmobile Skylark, built under a shared arrangement with Graham-Paige. Production delays and weak demand doomed the effort. Hupmobile ceased car production in 1939, and the company was effectively out of the auto business by 1940.

Detroit Electric: The early EV wave that faded

Long before Tesla, there was Detroit Electric. The Anderson Carriage Company began building electric cars in Detroit in 1907 and eventually rebranded its vehicle operation as Detroit Electric. Over roughly three decades it produced about 13,000 electric cars.

What Detroit Electric was famous for:

Detroit Electric marketed its cars to doctors and urban drivers who wanted reliable starting and didn’t want to hand-crank a gasoline engine. The cars were quiet, clean at the point of use, and could travel 60–80 miles on a charge in an era when most trips were short. Some models even used curved glass, which was technically advanced and expensive at the time.

What led to Detroit Electrics demise:

After World War I, gasoline cars became cheaper, faster, and easier to use thanks to electric starters and better roads. Electric cars lost their main advantages, and Detroit Electric’s sales collapsed from more than a thousand cars per year to just a few hundred. The company survived by building to order in tiny volumes until the last cars were shipped in 1939. The technology wasn’t inherently flawed; the business model was overwhelmed by cheap fuel and mass-produced gasoline cars.

Checker: Kalamazoo’s taxi that outlived its market

Checker Motors began as a Chicago-based taxi builder and moved production to Kalamazoo in the 1920s. It became a Michigan institution, supplying taxis to New York, Chicago, and other big cities.

What Checker was famous for:

The Checker Marathon became the stereotypical American taxi: roomy back seat, huge trunk, rear jump seats, and the black-and-white stripe along the side. The company kept the basic design in production—with updates for safety and emissions—from the 1950s into the early 1980s. Fleet operators valued Checkers for durability and ease of repair.

What led to its demise:

By the 1970s, the Marathon design was decades old. Federal safety and emissions rules added cost. As a low-volume producer, Checker could not match the pricing on fleet versions of full-size sedans from GM and Ford. The company considered replacements and even prototypes based on other platforms, but none reached production. Checker ended taxi production in 1982 and retreated into contract stamping for larger automakers. Rising raw material costs, shrinking orders, and tough negotiations with union labor pushed the company into bankruptcy in 2009. The last remnants were liquidated by 2010.

Great Lakes Auto Makers You Probably Forgot

Why these stories still matter in Michigan

Taken together, these independent makers show how crowded Michigan’s auto scene once was. Luxury specialists like Packard, innovators like Hudson and Detroit Electric, volume hopefuls like Durant, niche truck builders like REO, and purpose-built taxi makers like Checker all tried different strategies.

Most failed for the same cluster of reasons:

- Insufficient scale to spread tooling and development costs.

- Capital shortages that made it hard to launch new models on time.

- Economic shocks such as the Great Depression or the inflation and regulation waves of the 1970s.

- Tough mergers that looked like lifelines but often just postponed the end.

For Michigan communities, these firms were more than names on grilles. They were paychecks, neighborhood factories, and local pride. Their plants have been demolished, repurposed, or left as ruins, but their products still show up in museums, auctions, and small-town car shows across the state.

If you’re writing for a Thumbwind audience, these defunct independents offer a way to talk about Michigan history that goes well beyond the usual Big Three story—and connect readers to the streets, towns, and industrial buildings that once carried their badges.