The history of the Grindstone City quarry is a tale of industry, innovation, and a little village that once held a big place in the sharpening world. Tucked away at the tip of Michigan’s Thumb, Grindstone City started as an 1830s frontier outpost and grew into a global grindstone capital. For nearly a century, this town’s quarries produced the finest grinding stones, shipping them from the shores of Lake Huron to destinations around the world.

The rise and fall of Grindstone City, Michigan’s grindstone industry, offers a fascinating glimpse into how technology can build a community – and how new technology can just as swiftly bring it down. In this article, we’ll explore the origins, peak years, decline, and legacy of Grindstone City in a journey through time.

Table of Contents

Video – History of Grndstone City Quarry

Origins in the 1830s – A fortuitous discovery

The history of Grindstone City Michigan began with a twist of fate. In 1834, a schooner captain named Aaron G. Peer was caught in a storm on Lake Huron and took shelter near a rocky beach on Michigan’s eastern shore. When the storm passed, Peer explored the shoreline and found flat, abrasive stone slabs scattered about. Intrigued, he brought samples of this gritty sandstone to Detroit for testing. It turned out the stone was incredibly tough and ideal for grinding and sharpening tools.

In fact, some of Peer’s stone was used to pave a few blocks of Detroit’s Jefferson and Woodward Avenues – an early proof of its quality. Sensing an opportunity, Captain Peer claimed 400 acres of land in 1836 around the natural harbor where he’d landed. By 1838, he and his crew had crafted the first grindstones at the site, using simple hand tools and even rigging a crude grindstone to sharpen their own axes. This marked the humble beginning of what would become a major industry.

Michigan Thumbs First Industry

Throughout the 1840s and 1850s, more settlers and entrepreneurs arrived, drawn by the superior stone. They opened small quarries in the Marshall sandstone outcrops that ran through the area. These early quarrymen discovered that the stone came in layers: a “light” grade closer to the surface and a denser “heavy” grade deeper down. Both were excellent for making grindstones.

By 1850, Captain Peer’s operation was reportedly producing about $3,000 worth of grindstones annually – a sizable business for that era. Grindstone City wasn’t officially a town yet (it wouldn’t get its name until 1870), but a small community was forming around the quarrying activity.

Capt. Peer built a wharf and a water-powered stone mill, and he wasn’t alone for long. Other partners and investors joined, including individuals named Pierce and Smith who ran the quarry for a decade. They improved techniques, using horse-powered turning machines to shape the stones until a proper mill could be built. In these early years, grindstones from Huron County began to gain a reputation for quality. As one historical account notes, Grindstone City became synonymous with “the finest of abrasive stone” – a material not found anywhere else in the United States.

Boom Years: Grindstone Capital of the World

By the late 19th century, Grindstone City was thriving and had officially earned its place on the map. The village got its name in 1870, after a local conversation about the fast-growing settlement – one resident quipped it should be called “Grindstone,” another added “City,” and the name stuck. Indeed, by the 1880s it did resemble a small city built on stone. Several competing quarry companies had sprung up, consolidating over time into larger firms. In 1888, the Cleveland Stone Company purchased all the quarries and became the sole operator in town. They also took over the company store and other facilities, effectively making Grindstone City a company town.

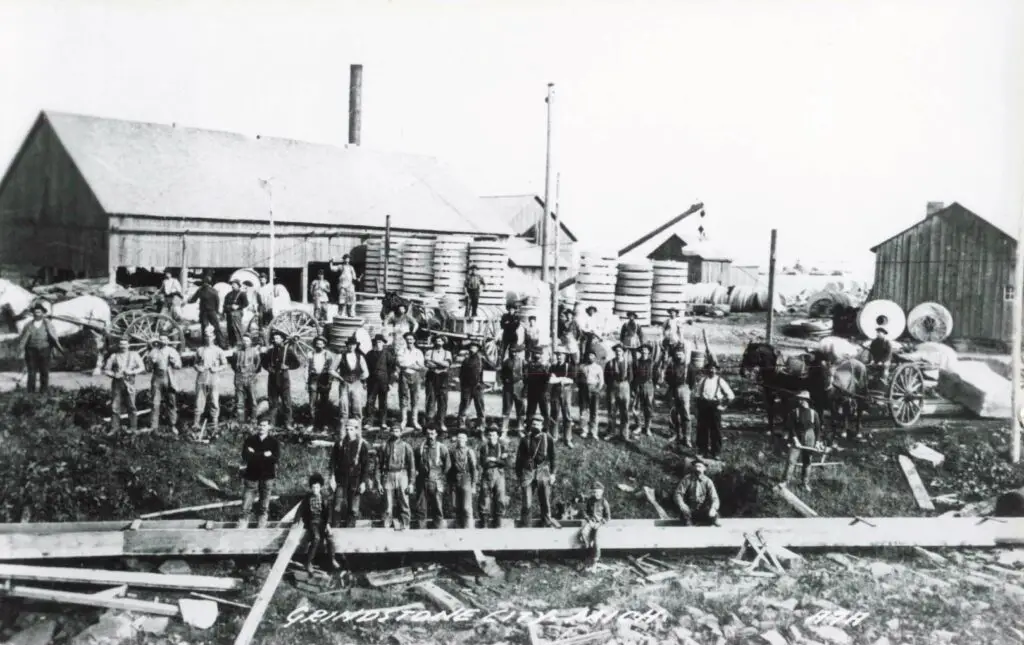

During this boom period, the grindstone industry dominated life in Grindstone City. The town’s population swelled to roughly 1,500 people by the late 1880s. Most residents were either stonecutters, quarry laborers, or family members of those working the quarries. The Cleveland Stone Company and a local outfit called the Wallace Company ran the show. They expanded the wharves and built two long loading docks, extending about 2,900 feet into Lake Huron to reach deep water. Grindstone City even had its own short-line railroad tracks. Flatbed rail cars would carry finished grindstones from the quarries directly onto the docks.

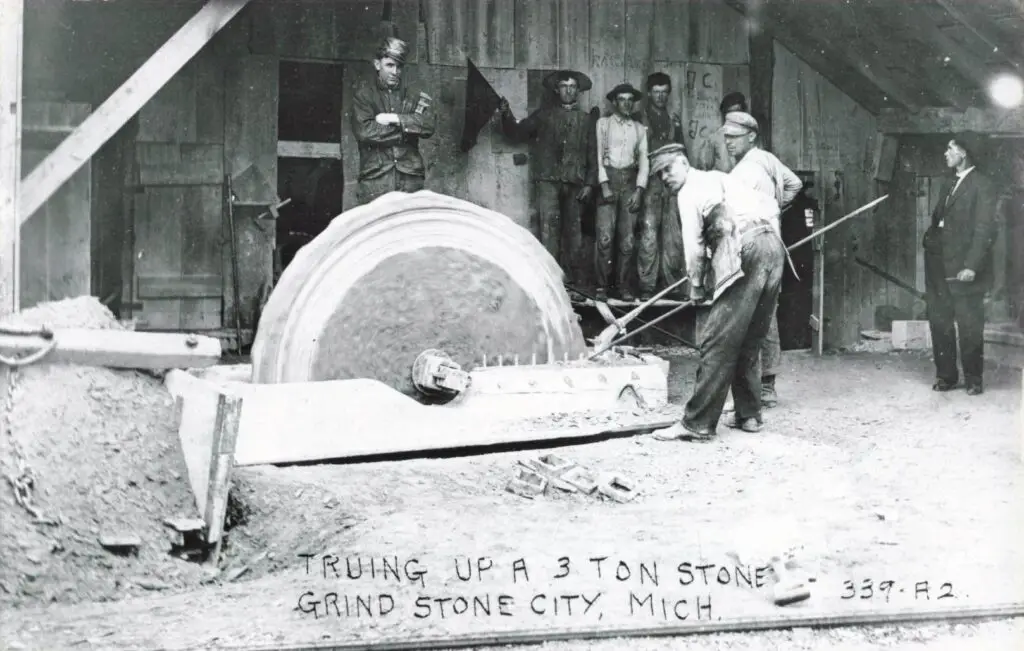

At the docks, the scale of Grindstone City’s output was on full display. Contemporary accounts and photographs describe hundreds of grindstones lined up and stacked for drying and shipment. The stones varied in diameter from small 6-inch whetstones to huge grindstones over six feet across. They also ranged greatly in weight – a kitchen sharpening stone might weigh 5 or 10 pounds, while the largest industrial grindstones weighed over 2–3 tons each.

The largest grindstone ever turned in Grindstone City tipped the scales at 6,600 pounds (around 3.3 tons). These massive stones required an entire team to move. Wooden derricks (lifting cranes) were stationed in the quarry pits to hoist big blocks of stone out of the ground.

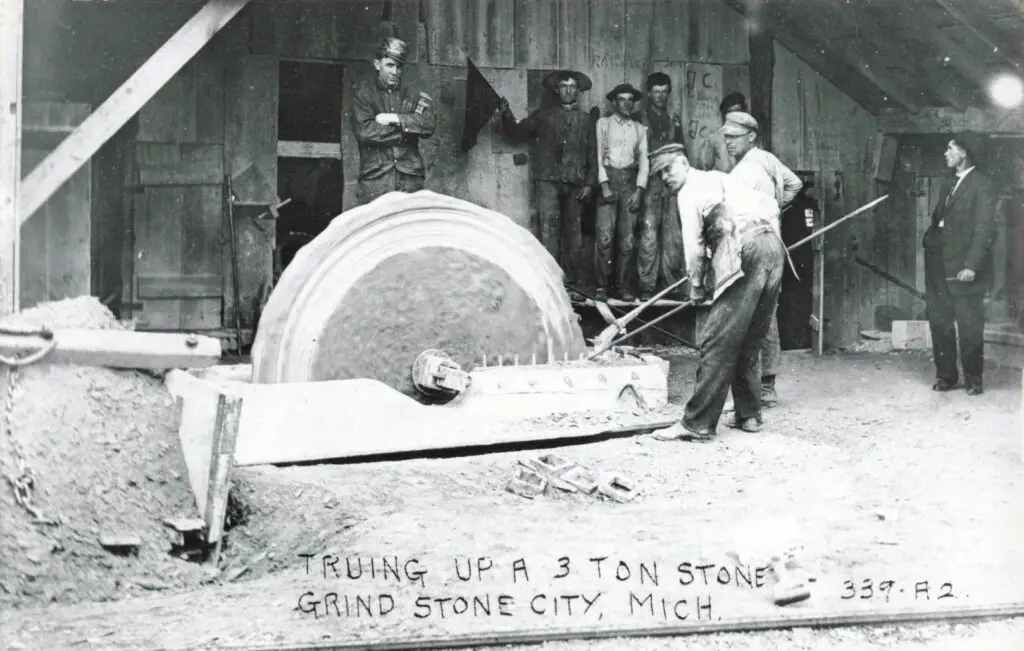

Steam-powered lathes and planers were used at the mill to true up the round stones. Skilled workers, often called stone cutters or turners, carefully shaped and smoothed each wheel. They took great pride in their work, knowing Grindstone City’s reputation was at stake with every shipment.

Grindstone City’s products were in high demand. Blacksmiths, factories, and farmers all needed quality grinding wheels to sharpen tools and process materials. Since this unique type of stone was found in quantity only at Grindstone City, the town enjoyed something of a global monopoly. According to the Friends of Grindstone historical site, grindstones from Grindstone City found ready markets in Canada, Germany, Russia, Africa, and across the United States.

A town made of stone

Ships would arrive all season long to load up. One by one, the giant wheels were rolled onto scows (flat barges), which ferried them to waiting steamships offshore. It was not uncommon for sailors to remark that the little town’s harbor was filled with “stone as far as the eye can see.” In these boom years, Grindstone City felt like the sharpening center of the world.

Daily life in the town revolved around the quarries. The company store (often referred to as the Grindstone City Trading Company or General Store) served as a grocery, supply depot, and social gathering spot. The owners paid workers partly in script usable at the store, a common practice in company towns.

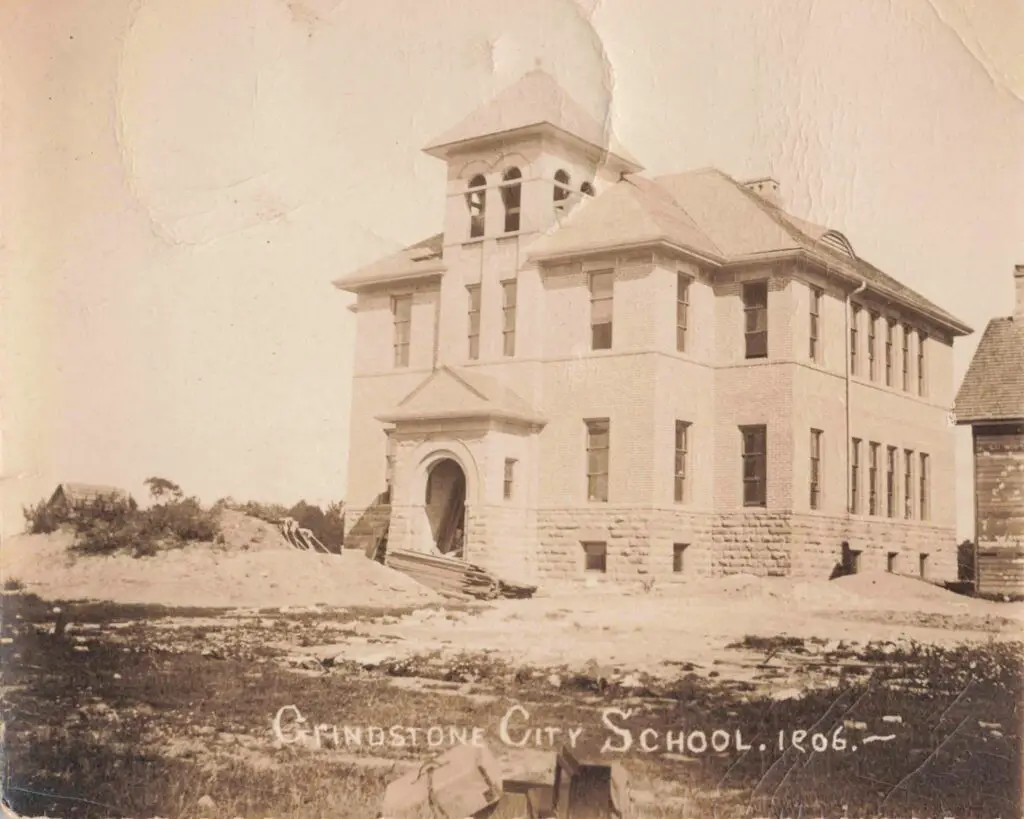

There was also a modern school (built in 1906) built south of the town and quarry where children learned reading, writing, and arithmetic. This public school in Grindstone City appears in a 1906 postcard image, showing a new brick and stone building still under construction. Churches were established as well, and a U.S. post office opened in 1872 (it operated until 1962).

For transportation, a short branch of the Port Huron & Northwestern Railroad ran into Grindstone City during the late 19th century, mainly to haul out lumber and goods, since the heavy stones went by ship. In sum, by the early 1900s Grindstone City was a prosperous little community. Observers at the time noted that “the finest grindstones, scythestones, and honestones in the world” came from this very place.

The Quarrying Life: Hard Work by Hand

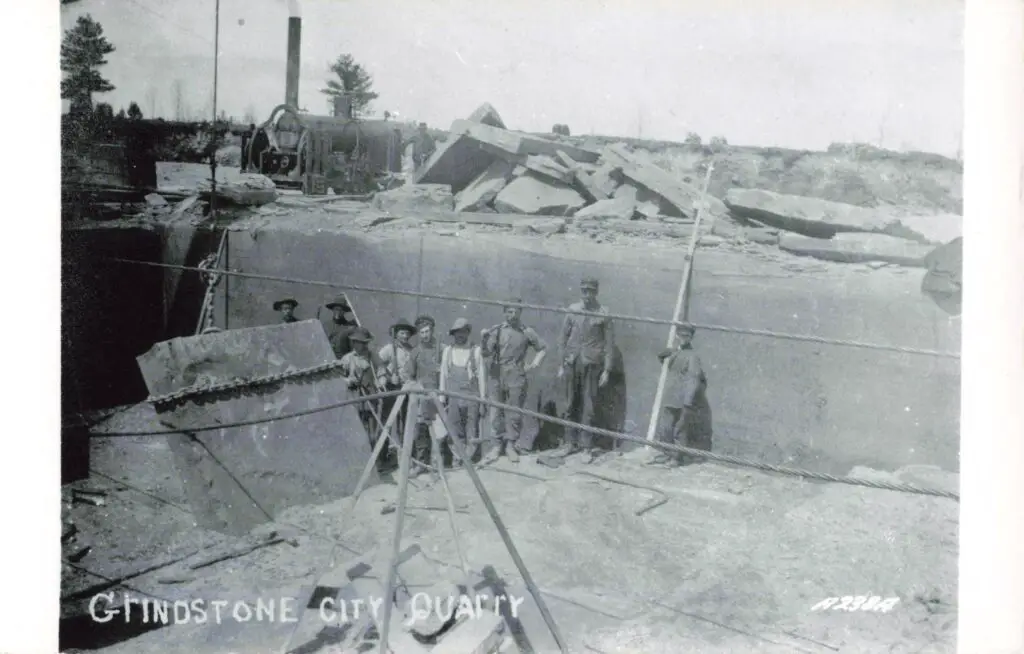

Quarrying stone in Grindstone City was exhausting, dirty, and dangerous work, but it was also a proud way of life for those who did it. Each autumn, crews would begin preparing a new section of the quarry for digging. They cleared trees and shrubs, and used horse-drawn scrapers to remove the topsoil. Beneath the soil lay layers of shale and overburden rock broken up by winter freeze-thaw cycles, which had to be pried off with picks and crowbars. By spring, once the ground thawed completely, the real quarrying began. Workers would “stake out” an area of sandstone big enough to yield all the stone needed for the season.

Drilling crews then hand-drilled or machine-drilled holes down into the rock in a grid pattern. In the early days this was done by hammer and hand drill, but later a steam drill made the job a bit faster. They might drill a series of holes and sometimes use small charges of dynamite to split the heavy stone layer from the bedrock below.

Quarrymen had to be extremely careful with explosives – too much could shatter the valuable stone. Often they stuck to more controlled methods: using wedges and hammers to break blocks free after initial cuts were made. Contemporary sources describe how quarry workers drove wooden or metal wedges into natural cracks to loosen large slabs. Once a slab (weighing several tons) was free, a team of men with pry bars would maneuver it and attach it to a waiting derrick. Using rope or chain slings, the derrick would then hoist the raw block up out of the pit onto the ground surface.

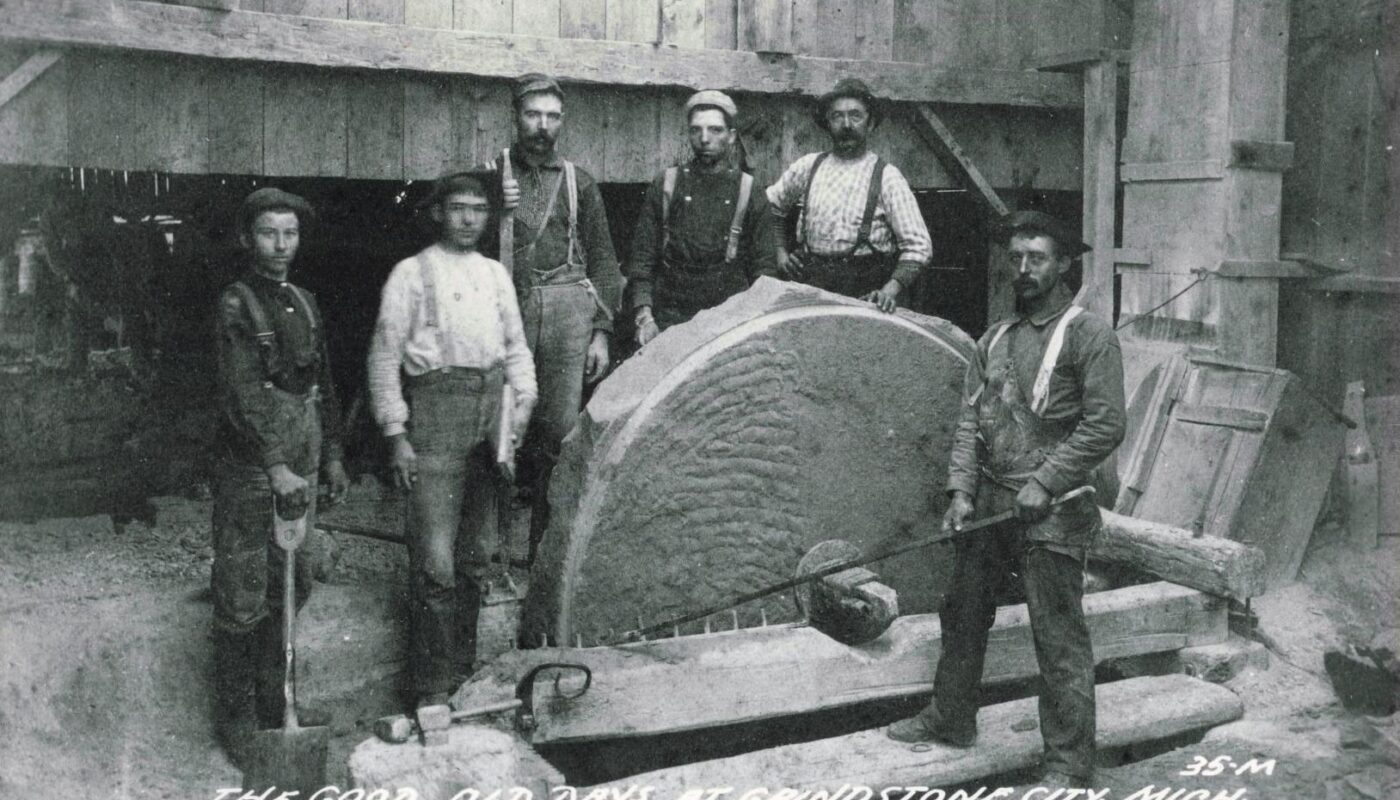

At the surface “stone yard,” other crews took over. They marked circles on the slabs and cut rough wheels out using chisels and saws. Early on, all turning (shaping of the round grindstone) was done by horse power – literally hitching a horse to a turning device. By the late 1800s, Grindstone City had water-powered and steam-powered lathes in its mills. A stone would be mounted like a wheel on an axle and spun, while a worker pressed a chisel or cutter to its edge to true it into a perfect circle.

This process, known as “truing up,” required skill to ensure the stone was balanced and had a flat face. An uneven grindstone could wobble or even crack during use, so quality control was important. Finished stones were drilled through the center to attach to grinding machines. They then spent weeks drying in the open air, to season and harden them before use. The company’s yard would have dozens of grindstones propped up in rows (an image of Grindstone City’s yard shows big circular stones looking like a forest of wagon wheels without wagons).

Workdays were long, often 10-12 hours, and safety was a constant concern. Stone chips flew from every hammer strike. Without modern safety gear, injuries were common. Still, many laborers stayed for years, proud of their craft. Oral histories recount how the quarrymen’s arms would swell with muscle from swinging hammers, and how even at rest their hands stayed curled as if still gripping tools. It was truly an era of manual labor – even as steam engines and rudimentary machines assisted, every grindstone bore the marks of human hands.

Decline After World War I: Innovation Changes Everything

No boom lasts forever. For Grindstone City, the beginning of the end came from a technological breakthrough far from Michigan. In 1893, American inventor Edward Acheson developed carborundum, also known as silicon carbide. This artificial abrasive could be mass-produced and formed into grinding wheels that rivaled traditional sandstone wheels. Initially, Grindstone City’s high-quality products held their own – many craftsmen still preferred natural stone for the finest sharpening. But as the 20th century progressed, carborundum and other synthetic abrasives improved and undercut the market with cheaper prices and larger production volumes.

By the early 1920s, demand for Grindstone City’s stones was fading fast. The Lake Huron quarries that once couldn’t keep up with orders now found their great piles of stone sitting unsold. The Cleveland Stone Company scaled back operations and closed some pits. Young people, seeing the writing on the wall, left town to seek work in cities or in automobile factories further south. The timing was cruel: just as the grindstone business faltered, the Great Depression hit in 1929. Grindstone City’s remaining quarry works shut down completely around 1929–1930, unable to turn a profit.

Almost A Ghost Town

The impact on the town was devastating. Virtually overnight, hundreds of people were out of work. Many families had to relocate, turning Grindstone City into a near ghost town by the mid-1930s. One historical source describes the scene: expensive grinding machinery was dismantled and shipped to Cleveland, while obsolete equipment was left to rust or was cut up for scrap metal in Detroit.

The once-bustling docks were deserted; one of the long piers later collapsed into the lake during a storm and was never rebuilt. In 1932, the post office even considered closing (though it survived a few more decades). The grindstone industry that sustained the town for 100 years was gone, disrupted by science and progress. As a local historian poignantly noted, this was “just one more example of science and technology killing an industry and a town… Such is progress”.

Legacy and Preservation – Remembering Grindstone City

While Grindstone City never revived as an industrial center, its legacy was not entirely lost. A few determined residents remained, and the area found new life as a fishing village and summer tourist spot in the following decades. The community’s pride in its past led to efforts to preserve some pieces of its history.

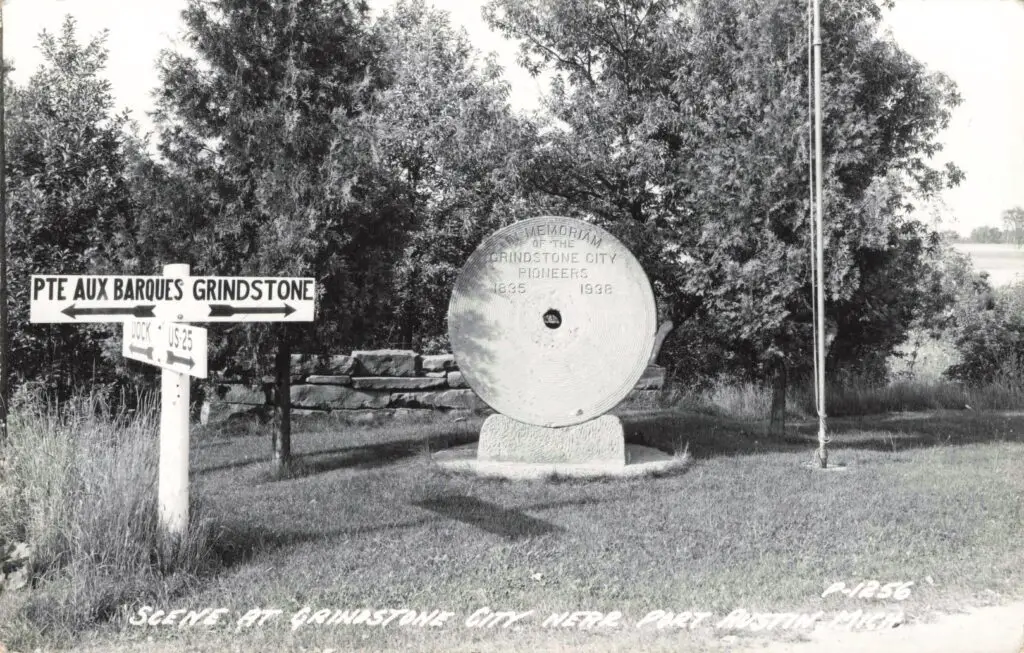

In 1935, the Cleveland Stone Company donated a colossal finished grindstone to serve as a monument for the town’s pioneers. This monument, weighing 4,750 lbs, was installed at the corner of Copeland and Rouse Roads in Grindstone City. It was dedicated by Dr. Wm. Lyon Phelps of Yale University (a summer resident of nearby Huron City) on September 3, 1935. The grindstone monument stands to this day, complete with a plaque honoring the men and women who “spent their lives working at the grindstone industry here.”

Many physical remnants of Grindstone City’s history can still be seen. Old grindstones are scattered throughout the area – it’s common to find them used as lawn ornaments, property markers, or even embedded in local foundations. The original Grindstone City General Store, built in 1886, is one of the last original buildings still in use. It operates seasonally as an ice cream parlor and gift shop, proudly claiming to be the “last remaining business from the original Grindstone City”. The store is in the process of being rebuilt after a fire in 2024.

Grindstone City is a designated historic district, and while much of it has returned to nature or private ownership, the story is kept alive by local history enthusiasts. The Friends of Grindstone organization, for example, shares photographs and tales of the grindstone quarries, ensuring new generations learn about this unique chapter of Michigan history. In recent years, visitors come to Grindstone City not for work but for leisure – fishing in the lake, boating, or stopping by the famous general store for a big scoop of homemade ice cream. Many probably don’t realize that the quirky round stone in front of the store or along the roadside is a genuine grindstone that could be over 100 years old.

Final thoughts about the Grindstone City Quarry.

The history of Grindstone City Michigan is a remarkable journey from boom to bust. It highlights how a small community carved out a place in the world, literally, with grit and determination (and a little luck in geology). From Captain Peer’s chance discovery of abrasive rock in 1834 to the town’s heyday as the grindstone hub of America, and finally to its quiet decline after 1930, Grindstone City’s story reflects the broader themes of American industrial history. Innovation can spark rapid growth, as it did for Grindstone City in the 19th century, and innovation can also render old ways obsolete, as seen with the rise of carborundum.

Yet, the legacy lives on. Grindstone City today may be small and off the beaten path, but it remains a cherished piece of Michigan’s Thumb region heritage – a place where the stones of the earth shaped not just tools, but the lives of an entire community.

Works Cited

Sonnenberg, Mike. “Grindstone City Trading Company.” Lost In Michigan, 6 June 2025. Accessed 24 Oct. 2025.

Robinson, John. “Michigan Ghost Town: The Rise and Fall of Grindstone City.” 99.1 WFMK, 2 Oct. 2019

Cook, Mabel. History of Grindstone City, New River and Eagle Bay. 1977. Excerpt in “Grindstone City” (GeoMichigan, Michigan State University Department of Geography) Accessed 24 Oct. 2025.

Friends of Grindstone. “History of Grindstone City.” Friends of Grindstone (community website), n.d. Accessed 24 Oct. 2025.