Linkville is a small unincorporated village in Huron County’s Winsor Township, in Michigan’s “Thumb” region. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries (circa 1890–1930), Linkville Michigan history began with a modest but active rural community. It began as a railroad stop and farming hamlet, and, despite never growing into a large town, it sustained a close-knit population with essential services: a railroad depot, a flour/roller mill, a general store, a hotel-tavern, a schoolhouse, and two churches. The period 1890–1930 saw Linkville at its historical peak, with agriculture and the railroad driving its economy and daily life. Below is a detailed exploration of Linkville’s history and lifestyle in that era, along with a timeline of major events.

Linkville Michigan History – Table of Contents

Video – Linkville Michigan History – Stories That Show Why This Tiny Town Still Matters

Founding and Early Development

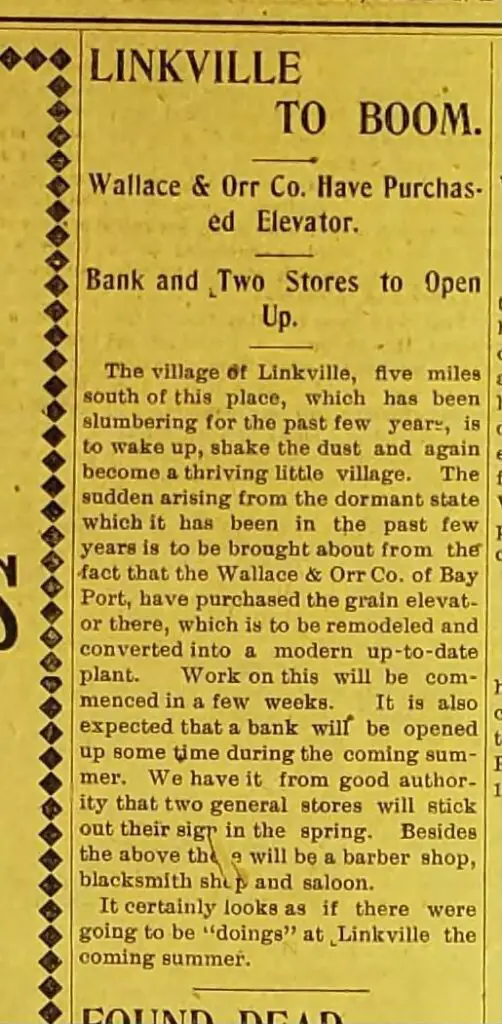

Linkville was originally founded around 1870 under the name Kilkenny. It arose near the Pigeon River in a region being rapidly settled after the Civil War. The coming of the Pontiac, Oxford & Port Austin Railroad (PO&PA) in the early 1880s was the critical catalyst for the village’s establishment. The PO&PA built a rail line northward through Huron County, reaching the vicinity by 1882–1883.

Linkville’s site, about 3 miles south of the newer town of Pigeon, became a scheduled stop on this railroad, initially intended as a minor station and postal stop. In 1879, a post office opened (under the name Kilkenny) to serve local farmers and rail workers. Although the first post office closed in 1883, it reopened in 1887 as settlement picked up again.

By 1893 the community was officially renamed Linkville, in honor of a local settler, Mr. Christian Link, who had become a prominent resident. According to a 1922 county history, Mr. Link and his family had moved to the area in the late 1880s and the village “was named after Mr. Link”. From that point on, the name Linkville appeared on maps and in postal records. Although Linkville was never incorporated as a village, it developed a small but stable population – roughly 100 residents in its heyday around the 1890s.

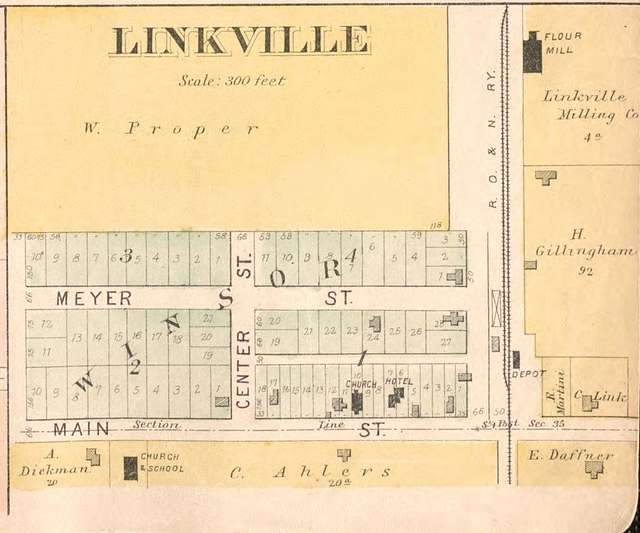

Map of Linkville from 1904. This early 20th-century plat map shows the village’s layout and key sites: the Pontiac, Oxford & Northern railroad line (formerly PO&PA) running north–south with a depot, the Linkville Roller Mill (“Flour Mill”) beside the tracks, and a grid of a few streets. Notably, a church and school are marked, along with properties of local families (e.g. land owned by the Link family).

The layout of Linkville in this period was simple. A short grid of streets formed the village center, with most buildings clustered near the railroad. Contemporary maps (e.g. the 1904 plat map above) show a north-south main road (today Kilmanagh Road) running through the hamlet, intersected by a couple of cross streets. The railway line ran parallel to the main road, and the station (depot) stood as a focal point on the west side of the tracks.

Nearby were the key businesses: the flour mill by the tracks, a general store, and a tavern/inn. Scattered around were residences and farmsteads, and just outside the platted area were farms that spanned the rich agricultural land of Winsor Township. Linkville’s cemetery was (and still is) located a short distance north of the village center on Stein Road, reflecting the community’s roots and the presence of a long-standing church congregation.

Economy: Agriculture and the Roller Mill

Agriculture was the economic backbone of Linkville from 1890–1930. The surrounding countryside consisted of fertile clay-loam farmland, ideal for growing grains (wheat, oats), dry beans, sugar beets, and other staple crops. Most Linkville families were farming families, and day-to-day life revolved around the seasonal rhythms of planting and harvest.

Huron County as a whole saw a boom in navy bean farming in the early 20th century – by 1910, over 20,000 acres of beans were under cultivation countywide. Local farms around Linkville contributed to this output, as well as to substantial wheat and sugar beet production. Notably, sugar beets became important after 1900 with nearby sugar factories (such as in Sebewaing), and beans were increasingly marketed through grain elevators rather than just general stores by the 1910s.

To support this farm economy, Linkville had a prominent flour mill, also referred to as a roller mill. This mill, shown in the historic photo below, was known as the Linkville Milling Co. and it processed local farmers’ grain into flour. Built likely in the late 19th century, the mill was a two-story frame structure, and by the early 1900s it was a central workplace in the village.

Farmers would bring wagonloads of wheat or other grain to be ground at the mill. The mill’s location directly beside the railroad track was strategic – it allowed milled flour and excess grain to be loaded onto rail cars for shipment to larger markets. Indeed, the Pontiac Oxford & Northern (the successor to the PO&PA line) primarily hauled farm products like wheat, beans, and sugar beets from rural stations such as Linkville.

During the 1890–1930 period, the railroad depot and the grain elevator in Linkville also facilitated commerce. A 1953 retrospective article noted that by mid-century Linkville had a grain elevator as part of the local farming infrastructure, which implies one was likely present earlier as well. Grain elevators would collect farmers’ harvests (beans, corn, etc.) for storage and rail shipment. The rail line itself was vital: it provided farmers with access to distant markets and brought in goods like farm equipment and household supplies. Freight trains stopped in Linkville to pick up carloads of grain or flour and to drop off coal, lumber, and merchandise for the general store.

Aside from farming, there is evidence of other natural resources in the area (Winsor Township had a noted limestone quarry and some timber in swampy tracts). However, those were nearer to Pigeon or in other parts of the township; Linkville’s identity remained primarily agricultural. There was a small sawmill established in the early 1880s near the township’s southern line, which may have provided lumber for local building. But by 1890, the great era of lumbering in Huron County had waned, and Linkville’s wooded areas had been largely cleared for farms.

Linkville Transportation and Travel

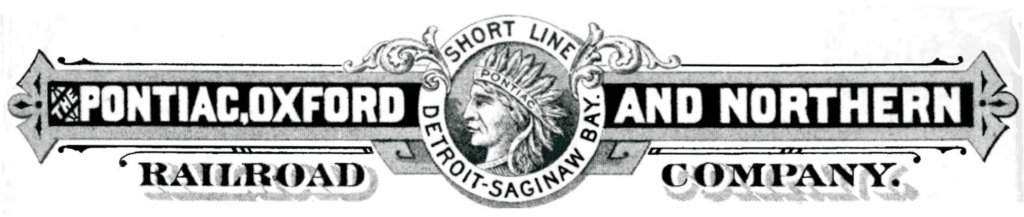

Rail transportation was the lifeline of Linkville around the turn of the century. The Pontiac, Oxford & Port Austin Railroad, completed in 1883, ran about 100 miles from Pontiac (north of Detroit) up to Caseville on Lake Huron. Linkville (initially called Kilkenny on the line) was one of the stops along this route, roughly 87 miles north of Pontiac according to later timetables. After a bankruptcy reorganization in 1889, the railroad was renamed the Pontiac, Oxford & Northern (PO&N). Eventually, in 1909, the Grand Trunk Western Railroad (GTW) took control of the line, dubbing it the “Cass City Subdivision”.

Throughout 1890–1930, the Linkville depot saw regular passenger and freight trains. Local residents could board a train to reach larger towns: a trip southward to Cass City or Pontiac, or northward to Caseville on the Saginaw Bay shore. Passenger service was modest (the Thumb region was sparsely populated, so ridership was limited), but it was crucial for those traveling before automobiles became common.

Farmers also used rail to ship goods and occasionally to travel to county fairs or markets. By the 1920s, automobiles and improved roads were starting to provide alternatives; a county road (now M-142 or nearby highways) connected the area to Bad Axe and beyond. However, in the 1890s and early 1900s, roads were dirt and often impassable in bad weather, so the train was the preferred link to the outside world.

The Linkville depot itself was likely a small wooden structure typical of rural stations – a “witch’s hat” style or simple gable-roofed building where the station agent handled freight and sold tickets. It served as a social gathering point when trains arrived. Local newspaper snippets from 1904 mention the station agent being relieved by substitutes, indicating that even tiny Linkville warranted a full-time agent at that time. The depot also handled mail during the years Linkville had an active post office. After 1913 (when the post office closed), mail was probably brought in by train and then distributed via rural routes from nearby towns.

By the late 1920s, automobile ownership in rural Michigan was increasing, and road improvements were underway. People began relying less on the train for short trips. The Grand Trunk Western likely discontinued passenger service on this branch by the 1930s as ridership dropped (specific dates are unclear, but many branch lines lost passenger trains around that time). Freight service continued for decades longer – in fact, the rail line through Linkville wasn’t formally abandoned until much later (1984 for the section north of Kingston), long after Linkville’s heyday had passed. But during 1890–1930, the sight of a steam locomotive pulling into Linkville with the whistle blowing was a routine and defining feature of village life.

Community Life and Daily Life in Linkville Michigan

Despite its small size, Linkville circa 1890-1930 was a self-sufficient rural community with a few key businesses and institutions that catered to residents’ daily needs:

General Store:

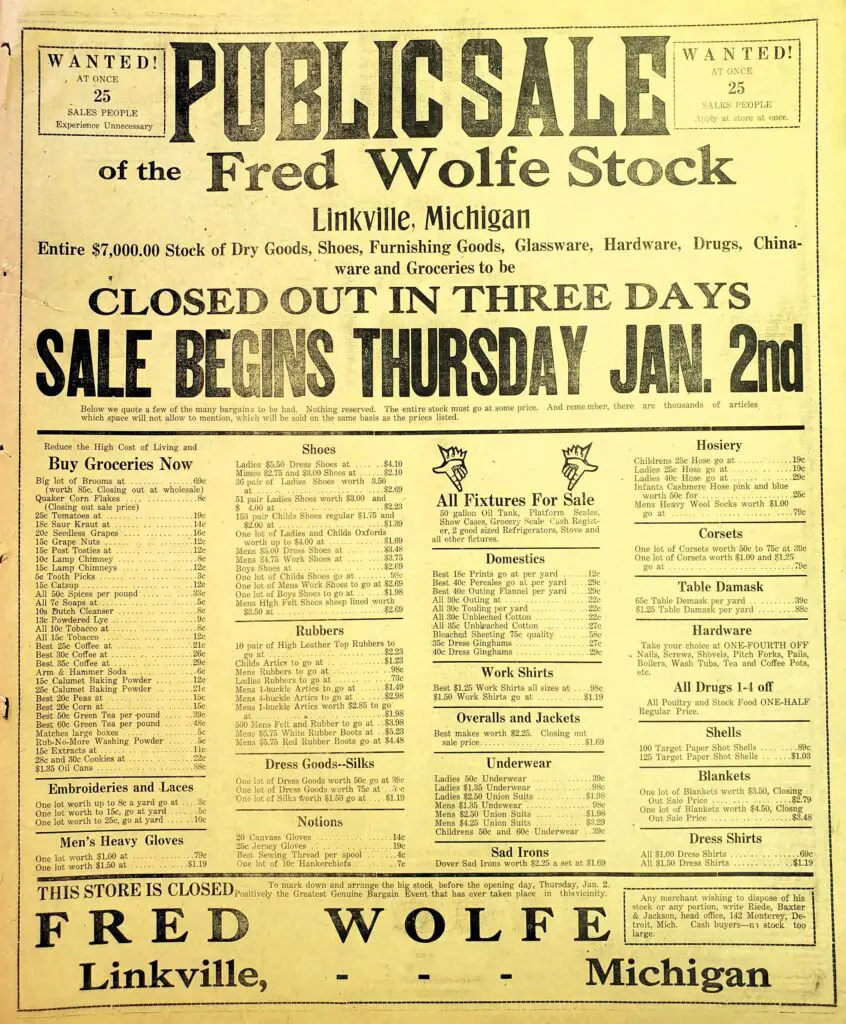

Linkville boasted at least one general merchandise store. In the 1910s, for example, J. G. Biegenscheid was listed as a dealer in general merchandise at Linkville, selling “a full line of dry goods, clothing, hats, caps, shoes, men’s and ladies’ furnishings, crockery, etc.”. Such a store would have been the village’s commercial hub, where one could buy groceries, tools, fabric, and farm supplies or trade produce for goods. The store likely also served as the post office during the years the Linkville Post Office operated (in small towns it was common for the storekeeper to double as postmaster).

Post Office:

The Linkville Post Office, when active, was a mark of the village’s viability. It operated intermittently: first from 1879–1883, then reopened in 1887. In 1893, the post office adopted the new name “Linkville” after Mr. Link, aligning with the community’s identity. It closed again in 1906, had one final reopening in 1907, and then closed for good in 1913. After 1913, residents used nearby post offices (such as Pigeon’s) or relied on rural free delivery. The loss of the post office in 1913 is a notable point in Linkville’s decline as an independent village, since a post office was often key to a town’s survival.

Hotel and Tavern:

Linkville had a hotel/tavern that provided lodging, food, and drink for locals and travelers. A county directory from the 1910s lists Henry C. Fischer as proprietor of a hotel and saloon in Linkville, advertising “first-class accommodations” and “fresh beer always on tap”. This establishment likely served multiple roles: a place for railroad passengers or drummers (traveling salesmen) to spend the night, a local saloon for farmers to socialize (especially on weekends or after market days), and possibly a dining hall. In a community of around 100 people, the tavern was an important social center alongside the churches.

It’s worth noting that Prohibition (1920–1933) would have forced the saloon to stop serving alcohol – during those years it may have operated as a soft-drink parlor or simply as a boarding house. The presence of a “tavern” is specifically recalled in local histories as something Linkville lost over time: “After the post office, tavern and train left, the only thing that remained… was the local church,” a Huron Daily Tribune article quipped, indicating how pivotal that tavern once was.

Schoolhouse:

Education for children in Linkville was initially provided by a one-room schoolhouse serving the rural district. Early records mention that Winsor Township organized several school districts in the 1880s (for example, a school in Section 10 and another in Section 28). Linkville’s children likely attended a nearby country school; the 1904 map indeed labels a “School” within the village plat, suggesting a local school building existed by then. Classes would have been basic, often taught in German and English if many students were of German descent (which was common in the Thumb area).

Later, St. Paul Lutheran Church itself established a parochial school in 1926 (more on this in the church section), but before that, a public one-room school would have served the community. The schoolhouse would also double as a venue for social events – possibly hosting Christmas programs, pie socials, or public meetings, given its status as one of the few community buildings.

Population and Culture:

The population of Linkville in this era hovered roughly around one hundred residents. Many were German-American farmers – indeed, Winsor Township and surrounding areas had been settled heavily by German immigrants (as evidenced by family names like Link, Ahlers, Lucht, Ruthig, Woldt, etc., and by the establishment of a German Lutheran church).

German language and customs likely featured in community life: church services at St. Paul were probably conducted in German into the early 20th century, and everyday conversation in homes and at the general store may have been a mix of German (“Low German” dialects) and English, until World War I era patriotism accelerated the shift to English. Culturally, the village was conservative and family-oriented. Aside from church gatherings, popular leisure activities would have included neighborly visits, barn dances or fiddle music at the tavern, and possibly baseball games in summertime (rural towns often fielded baseball teams).

Overall, life in Linkville was quiet and hard-working. Most residents rose early to tend livestock and fields. Travel to the nearest larger town (Pigeon, population a few hundred by 1900) was occasional – perhaps for special shopping, medical needs, or banking – because Linkville itself could meet basic needs. The close proximity of Pigeon did, however, influence Linkville’s trajectory. Pigeon, located just a couple of miles to the northeast, grew rapidly after 1886 when another railroad (the Saginaw, Tuscola & Huron, later Pere Marquette) was built east–west through the area.

Pigeon soon boasted multiple churches, stores, and an incorporated government. In contrast, Linkville remained a hamlet. Many Linkville residents would go to Pigeon for high school (once consolidated schools opened), for larger stores, or to catch connecting trains. The rise of Pigeon likely drew commerce and population growth away from Linkville, reinforcing Linkville’s status as a “shadow town” or ghost town in the making even before 1930.

Churches and Institutions of Faith

One of the most enduring legacies of Linkville’s history is its churches, especially St. Paul Evangelical Lutheran Church, which remains active to this day. In the 1890–1930 timeframe, two churches served the village, reflecting the importance of faith and community for its residents.

St. Paul Evangelical Lutheran Church (Linkville): This Lutheran congregation was founded in 1894 and became the spiritual heart of Linkville. According to church history, St. Paul began humbly – the first members met in a house in 1894 and soon purchased a hay barn in the village to convert into a place of worship. For the next 30 years, that repurposed barn served as the congregation’s church. Despite its unconventional nature, the little Lutheran church-in-a-barn thrived: it started with about 20 members (mostly local farm families of German Lutheran background) and gradually grew. Worship was likely led in German in the early years by pastors who traveled or served multiple country churches.

In 1924, a significant development occurred: the congregation obtained a new dedicated church building. They moved out of the old barn and into this new structure, which is the church building still in use in Linkville today. The new St. Paul church (built in 1924) was a modest yet proper house of worship – over the years, it acquired a bell tower and stained-glass windows, but even initially, it would have been a step up from the barn. The church sat along the main road, a simple white-frame building typical of rural Lutheran churches.

St. Paul Lutheran anchored community life through regular Sunday services, holiday celebrations, weddings, funerals, and youth catechism classes. It also launched a parochial school in 1926, reflecting the value placed on Christian education. Pastor Suggitt (the church’s current pastor in 2019) recounted that the school began in 1926 with 18 students, teaching both general subjects and religious instruction. Although that Lutheran day school only operated until 1952, its establishment in the late 1920s shows that by the end of our period, the congregation was robust enough to support a teacher and classroom for local children. (After 1952, St. Paul’s school became a Sunday school program).

The church’s endurance is notable: even as other Linkville institutions faded, St. Paul Lutheran remained – “The train stop has come and gone… the tavern has come and gone, the post office has come and gone. But St. Paul still remains there in Linkville after all these years,” as Pastor Suggitt put it.

The Evangelical Church: In addition to the Lutheran congregation, Linkville had a second church often referred to simply as the “Evangelical Church.” This was likely affiliated with the Evangelical denomination (possibly the Evangelical Association or a similar Protestant group with German roots, which later became part of the Evangelical United Brethren). Little specific documentation survives about this church, but local memory, plat maps and photographs confirm its presence.

A historic photo labeled “Evangelical Church, Linkville, Mich.” (see below) shows a small white church with a front belfry, distinct from St. Paul’s building. The two churches stood not far apart – each serving a portion of the populace. It’s possible the Evangelical Church was established earlier (some sources note an Evangelical congregation in the township dating back to the 1860s in nearby Kilmanagh) or around the same time as St. Paul’s, to serve those of a different Protestant persuasion (perhaps those who were part of the Evangelical Association movement rather than Missouri-synod Lutheran).

During the 1890–1930 era, having two churches was remarkable for such a small village – it underscores the dense patchwork of ethnic churches in rural Michigan. St. Paul was Lutheran (German Lutheran tradition), and the Evangelical Church was probably part of the Evangelical Association (a Methodist-related German Protestant tradition). The congregations would have held separate services and events, but likely cooperated for certain community-wide functions. For example, they might jointly host a picnic or respond together to any local crisis.

The Evangelical Church likely did not survive much beyond the 1930s or 1940s; as the population dwindled, its members may have merged into other nearby congregations (perhaps an EUB church in Pigeon or Elkton). By the late 20th century, it had disappeared, leaving St. Paul’s Lutheran as the lone church, which is precisely what happened in Linkville’s case.

It’s important to note how central faith was to daily life: Church attendance on Sundays was nearly universal, and church festivals (Christmas programs, Easter services, midsummer picnics) were highlights of the social calendar. The churches also reinforced cultural identity, especially for the many German immigrant families – sermons, hymns, and catechism in German helped preserve their language and customs until Americanization became stronger in World War I’s wake.

A Boom on the Horizon: Linkville’s Brief Revival Hopes

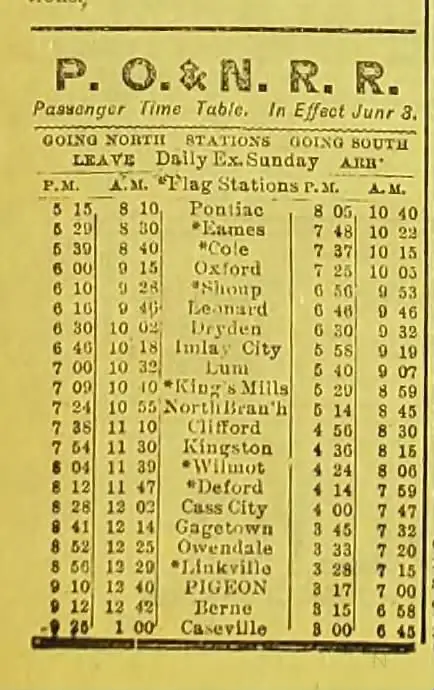

In what seemed like a turning point for the sleepy hamlet, a news article published in the early 1900s announced that Linkville was poised to “wake up, shake the dust and again become a thriving little village.”

The catalyst? A business move by Wallace & Orr Co. of Bay Port, who had purchased the local grain elevator with plans to remodel it into a modern, up-to-date facility. Work was expected to begin within weeks. The article stirred local excitement, forecasting a potential economic revival. Alongside the mill upgrade, plans included the opening of a bank, two general stores, a barbershop, blacksmith shop, and the return of a saloon.

The tone of the piece was optimistic—possibly overly so. “It certainly looks as if there were going to be ‘doings’ at Linkville the coming summer,” it proclaimed. For a small village that had seen steady decline, these developments hinted at a comeback.

However, there’s little evidence the boom fully materialized. The elevator was likely upgraded, but the other promised businesses never became lasting fixtures. Still, this clipping reflects a community hoping for revival—and shows how closely tied Linkville’s fate was to the flow of agricultural trade and railroad logistics.

Linkville’s Decline Towards the 1930s

As the 1920s gave way to the 1930s, Linkville’s brief flourishing began to wane. Several factors contributed to its decline:

- The loss of its post office in 1913 meant Linkville was no longer an official postal town, which often foreshadows diminishing business activity.

- Improved transportation meant residents could travel to larger towns (like Pigeon, Sebewaing, or Bad Axe) for goods and services. Cars and trucks became more common by the late 1920s, so farmers might bypass the local general store to shop in Pigeon, or ship grain by truck instead of rail.

- The railroad’s importance for passengers declined, and small depots saw less traffic. While freight still moved, rail consolidation under Grand Trunk likely meant fewer stops at tiny stations like Linkville except when needed.

- The onset of the Great Depression (1929), just at the end of our period, would hit rural communities hard. Farm prices collapsed (notably, the price of beans, a local staple, hit record lows by 1933), and many country stores and mills struggled to survive the lean years of the early 1930s.

By 1930, Linkville was slipping into obscurity. It never truly “boomed” beyond its initial ~100 residents, and it never incorporated as a village. The next decades saw it recede into what one might call a “ghost town.” As one modern writer observed, “Nowadays all that’s left is one of the churches and a few old houses scattered throughout the countryside”. Indeed, St. Paul Lutheran Church endured and became the sole landmark anchoring “Linkville” on the map.

The church’s continued presence (celebrating 125 years in 2019) is a testament to the legacy of those early settlers. The old mill, depot, store, and second church are gone or fallen to ruins, but during 1890–1930 they were alive with activity, serving a community that worked the land and gathered together for worship and fellowship.

Timeline of Key Events in Linkville Michigan History (1870–1930)

- 1870: Village founded under the name Kilkenny near the Pigeon River as a stop along the planned Pontiac–Port Austin rail line. Early settlement is minimal at first.

- 1879: U.S. Post Office established, named Kilkenny. This marks the first formal recognition of the community.

- 1883: Kilkenny Post Office closes (the rail stop and settlement nearly fade out).

- 1883: Pontiac, Oxford & Port Austin Railroad is completed through Winsor Township, providing rail service. The line passes through the future Linkville area.

- 1887: Post Office reopens due to local demand (many new settlers arriving in the 1880s). Mr. Christian Link and family settle in the area around this time.

- 1893: The community is officially renamed Linkville (honoring Christian Link). The post office adopts the name Linkville in this year.

- 1894: St. Paul Evangelical Lutheran Church is founded in Linkville. The first meetings are held in a house, and a barn is purchased to serve as the congregation’s church.

- Late 1890s: Linkville reaches roughly 100 residents. A general store, a flour mill, two churches, a depot, a hotel (“motel”) and a schoolhouse are present by the end of the 19th century. Farming and local commerce are thriving on a small scale.

- 1889: The PO&PA Railroad goes bankrupt and reorganizes as the Pontiac, Oxford & Northern Railroad, reflecting the sparsely populated region’s low passenger revenue.

- 1906: Linkville Post Office is closed (second time), interrupting local mail service.

- 1907: Post Office reopens again (last brief stint).

- 1909: Grand Trunk Western (GTW) acquires the Pontiac & Northern line, integrating it into a larger railroad system. Rail operations in Linkville continue under GTW management (now called the “Cass City Subdivision”).

- 1913: Linkville Post Office is closed permanently. After this, Linkville addresses use neighboring towns (Pigeon) and rural free delivery. This year effectively marks the end of Linkville’s official status as a town.

- 1920: National Prohibition begins. Linkville’s tavern ceases alcohol sales (likely impacting the hotel-saloon business).

- 1924: St. Paul Lutheran Church moves from the old barn into a new church building bought or built this year. This new building (with subsequent additions like a belfry) will serve the congregation for the next century.

- 1926: St. Paul Lutheran opens a parochial school with 18 students, indicating the congregation’s growth and the community’s commitment to education.

- Late 1920s: Linkville’s population continues to dwindle or stagnate. Improved roads and automobiles start connecting farmers directly to larger markets, reducing dependence on the tiny village center.

- 1929: The Great Depression begins. Farm commodity prices collapse; the local economy suffers. Many young people leave farms for work elsewhere in the 1930s, contributing to Linkville’s decline.

- 1930: By this year, Linkville is effectively a hamlet with only a handful of businesses left. The railroad depot likely still operates for freight, but passenger service may be infrequent or ended around this time (exact cessation unknown). The Evangelical Church may have already or soon held its last services as membership shrank. St. Paul Lutheran, however, remains active and will become the enduring symbol of Linkville on into the later 20th century.

In summary, between 1890 and 1930, Linkville transformed from a nascent rail-stop settlement into a small but vibrant farming village, and then gradually retreated into obscurity. Its story is emblematic of many rural Michigan communities that flourished briefly with the railroads and pioneer farming, only to fade as transportation and the economy changed. Yet, the historical features visible in old images – the sturdy roller mill, the little depot, the simple churches, and the grid of village streets – all speak to a bygone era of local industry, faith, and rural community spirit. And notably, the St. Paul Evangelical Lutheran Church, established in 1894, continues to stand at the heart of Linkville, linking the present to the village’s rich past.

Linkville, Michigan History Sources

- Florence McKinnon Gwinn, Pioneer History of Huron County, Michigan (Bad Axe: 1922), for early Winsor Township background.

- Huron County plat maps and directories (1904, 1910s) for Linkville layout and businesses.

- John Robinson, “Shadow Town in the Thumb: Linkville, Michigan,” 99.1 WFMK (Jan. 30, 2019) – overview of Linkville’s history.

- Andrew Mullin, “125 years in the making – Church in Linkville to celebrate milestone” Huron Daily Tribune (July 30, 2019) – history of St. Paul Lutheran Church.

- Huron County View (Aug. 2019), “St. Paul-Linkville celebrating 125 years,” confirming church founding dates.

- “Ghost Towns of Huron County – Linkville,” Huron County EDC (2020).

- Michiganrailroads.com and AbandonedRails.com – history of the Pontiac, Oxford & Port Austin / Northern Railroad

- Michigan Tradesman 1953 Huron County edition (as summarized by Walt Rummel, Huron Daily Tribune, 2009) – details on agriculture (bean and grain production) and mention of a grain elevator at Linkville.

- Archive records from Rawson Memorial Library (Cass City) – business directory entries for Linkville’s hotel and store.

- U.S. Geological Survey / GNIS for the geographic location of Linkville and Linkville Cemetery.