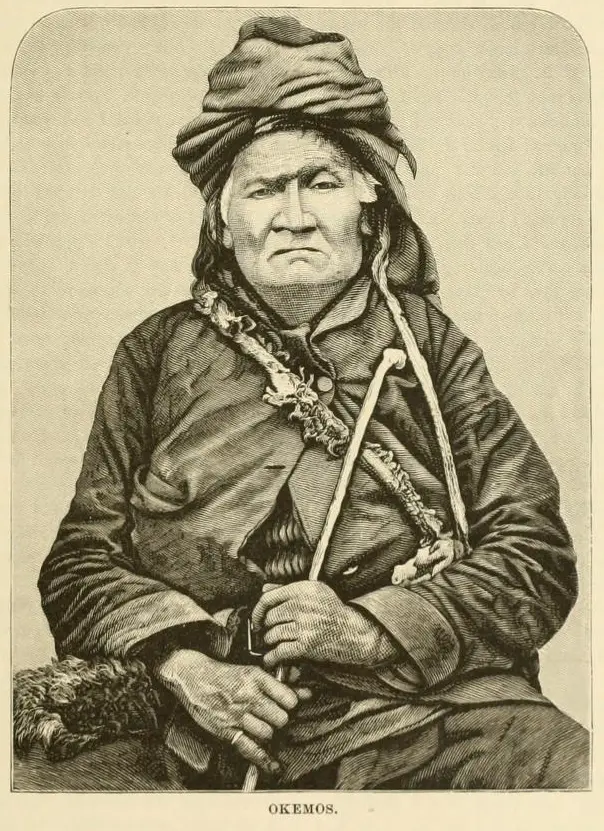

This is a story by Ephraim Williams of the Anishinaabeg history (aka Ojibwa) of hunting and gathering in the land of a Sauks. The Ojibwa believed that misfortune was due to the bad spirits that the Sauks had left behind.

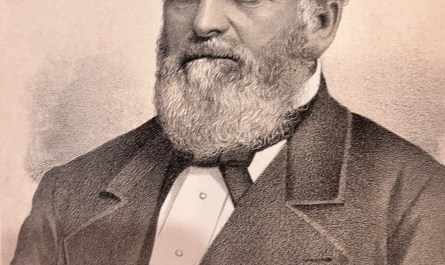

Ephraim Smith Williams was the seventh mayor of the Village of Flint, Michigan, serving from 1861 to 1862. He was a land merchant. Married to Hannah Melissa Gotee on March 13, 1825. He was born on February 7, 1802, and died on July 20, 1890. This story was published in 1888 in volume 10 of the Michigan historical collections. It has been edited for online publication.

The Defeat of the Sauks in Saginaw Valley

I notice with pleasure an article upon the defeat and extermination of the Sauks from the Saginaw country by the Chippewas and other tribes, which I have always understood to be the fact, and Saginaw derives its names from the fact of its having been the Sauks’ country, the Indian name being Sawgee-nong, meaning the Sauks’ country, also as regards their superstitions and notions that the country they had captured from the Sauks was haunted

by the Mun-e-soos or bad spirits of the Sauks, or in their phrase, the bad Indians. I will give a little of my experience of twelve years’ residence among them.

They carried their fears and superstitions to a great length and, at many times, their very great property loss. I have witnessed many of their frights and have tried to persuade them otherwise but to no purpose. They have been deluded for so long.

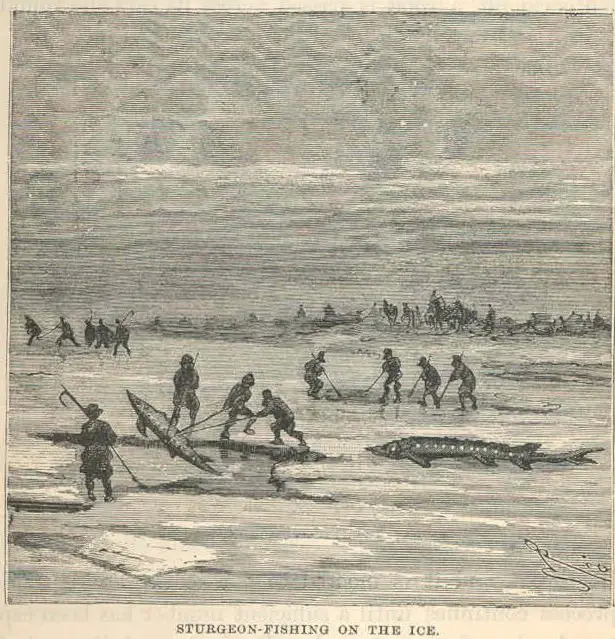

Sturgeon Gathering By the Anishinaabeg

There was a time, every spring when the Indians from Saginaw and the interior would congregate in large parties upon the Saginaw bay to put up large quantities of dried sturgeon, which made a very delicate dish when properly cooked and was much used in those days, by the first families in Detroit.

At the Point Au Gres, so-called in those days, being a shallow point making out into the bay, with a smooth limestone bottom, the sturgeon would run up the smooth point in large numbers, working up until quite up the shore, and lie like floating cordwood.

The Indians camped here on the point and would select the best at their leisure, flay them, hang them across poles in rows about four feet from the ground and the rows about two or three feet apart. Then a gentle smoke was kept under them until perfectly dry. A common-sized sturgeon, when flayed, would be about the size of ordinary deerskin. They were folded and packed in nice packages for keeping for their summer use and for the market when dry.

Fear of the Mun-E-Soos

About the time this is accomplished, the Mun-e-soos, more properly poor, lazy, worthless Indians, would come from a distance, having an eye to supplying themselves with provisions they never labored to obtain, except by theft. They (the Ojibwa) would now commence, in different ways, to excite their fears that the Mun-e-soos were about their camps by firing guns at night in the woods in the rear of their camps, and also dropping a certain painted kind of quills near their camps so the children and women would find them. These were certain indications their enemies were near at hand.

After a few nights, they became so frightened that they would take to their canoes and flee, leaving almost everything they possessed, fleeing for the Saginaw River. The Mun-e-soos or robbers would then rob their camps of what they wanted and escape to their homes, with perhaps their summer supplies of fish and often sugar and dried venison. They rarely, if ever, took any articles of property, as it might lead to discovery and detection.

Being the time of year, I usually made my annual trips along the bay and lakeshore, looking after our spring trade and collection of furs, going as far as Thunder Bay and looking after our trading post at the Sable River, where we kept three men during the winter, at these times I have often met them fleeing as above mentioned, sometimes twenty or more canoes. I have stopped them and tried to induce them to return, and we would go with them; but no, it was the Mun-e-soos, and nothing would convince them differently, and away they would go frightened almost to death.

The Ojibwa Would Leave Everything Behind

I have visited their deserted camps at such times, gathered up their effects that were left, and secured them in someone’s camp or lodge from the destruction of wild animals. After a time, they would return and save what was left.

During these times, they were perfectly miserable, actually afraid of their own shadow. At other times, having a little bad luck in trapping or hunting, they would become excited and often say the game has been over and in their traps and they don’t catch anything–have known them to go so far as to insist that a beaver or an otter has been in their traps and has gotten out, or was let out by the Mun-e-soos, or that their traps are bewitched or spellbound by the “bad Indians,” that their rifles have been charmed by the Mun-e-soos and they can’t kill anything.

Then they must give a great feast and have the medicine man or conjurer, and through his wise and dark performances, the charm is removed, and all is well again; traps and rifles do their duty, and the poor beaver, otter, deer, bear, etc., again suffer, much to the profit of the traders and pleasure of the Indians. These things have been handed down for generations.

Ojibwa As Marksmen

I have had them come frequently miles, bringing their rifles to me, asking me to examine and re-sight them, declaring the sights had been moved, and in most instances, they had (but by themselves in their fright). I always did, when applied to, re-sight and try them until they would shoot correctly, and they would go away cheerful and thankful. I would tell them they must

keep their rifles and traps where the Mun-e-soos could not find them.

They never forgot these little favors but would bring me some choice present, such as beaver’s tails, which are a most delicate dish, and often a nice fat ham of venison. Their coming to me was that I always kept a splendid rifle and was considered a good marksman.

The young hunters would come and practice shooting at a mark with me. I have spent hours shooting with them. They thought it very strange I would beat them shooting offhand, and they always rested their rifles. I have practiced with hundreds of them and never found an Indian I could not beat at any distance. This fact made me quite popular with them.

The Anishinaabeg Feast

I have often attended their feasts by invitation. These are always conducted with much solemnity, and the invited guest or guests are always seated at the head of the feast, and the head of the animal cooked for the feast is always placed in a dish before the guest. Sometimes it is a bear, deer, coon, or dog, a dog being esteemed as their greatest delicacy.

They usually, at these feasts, after the table is cleared away, close with what is called a Pouch Dance, which is a very solemn affair, but very amusing to the guests, the guests never being allowed any part therein.

An Anishinaabeg Boy Rides a Sturgeon Like a Horse

I meant to have mentioned an incident, which was very amusing. When the sturgeon runs up on Point Au Gres, some are very large and lie quite stupid. A young Indian, a little fellow, would wade in, straddle one of these, strike his tomahawk into its nose, and away the sturgeon goes full speed through the water, the young Indian guiding him by the handle of the tomahawk until fatigued, then runs him ashore, to the amusement of lookers-on, the young fellow receiving many cheers.

Some of these fish are very large, often weighing one hundred pounds or more. The Indian name for sturgeon is mon-e-meg.

In Mr. Williams’ “Personal Reminiscences,” in vol. VIII of Pioneer Collections, he calls the evil spirits “manesous,” and instead of the Sock Indians, he calls them Sauks. In Long’s Chippewa vocabulary, sturgeon is translated onnemay instead of mon-e-meg.

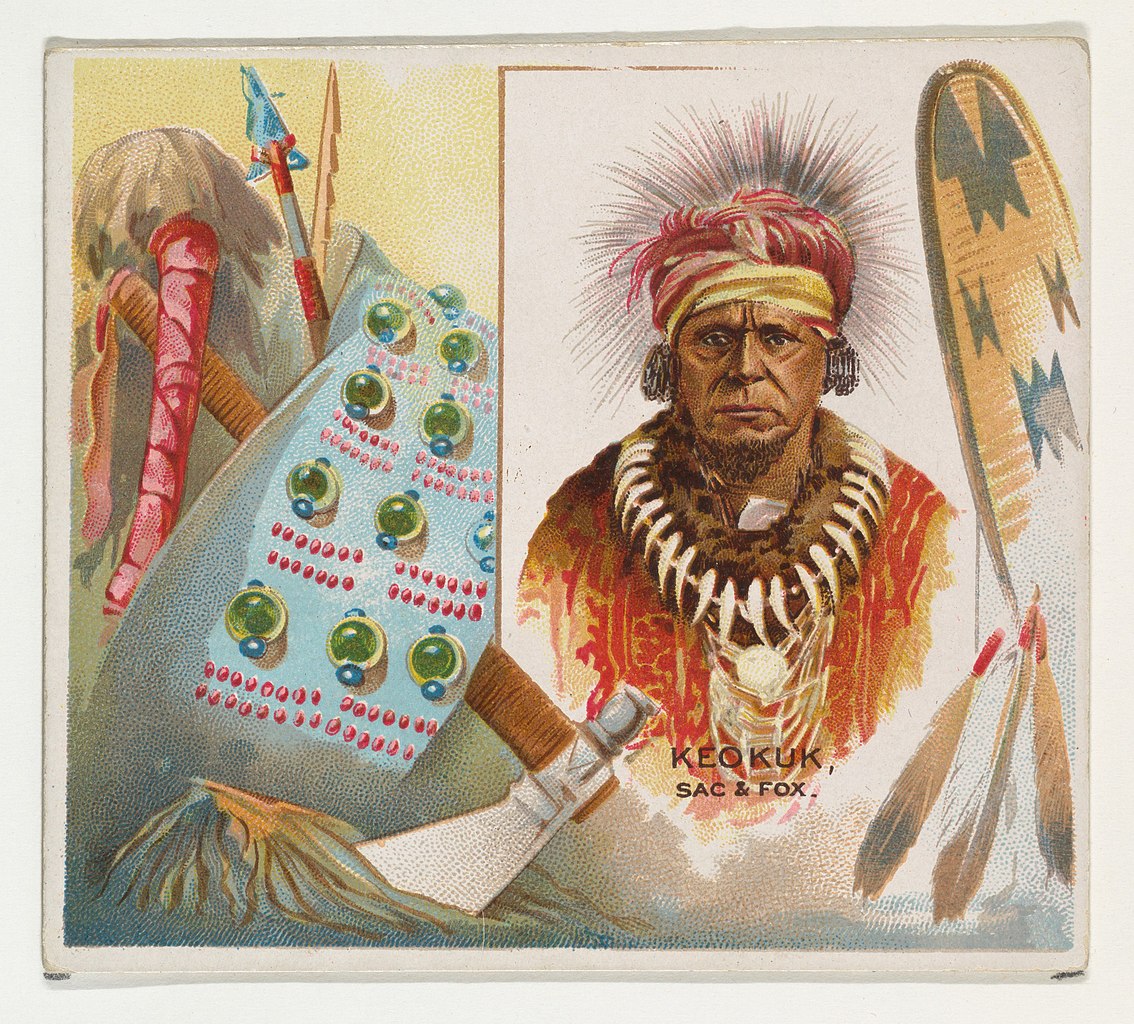

Featured Image of Sauk Chief by Allen & Ginter , CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Related Anishinaabeg History Reading

The Horrid History Of 3 Indian Boarding Schools In Michigan

The Mystery Of The Remains Of An Indian Chief Found Near Bay Port

Michigan Indian Villages And Sites In Huron County

Michigan Indian Chief Standing Oak Defeated The Fox Tribe Near Sebewaing

One thought on “2 Short Stories Of Anishinaabeg History In Saginaw Valley”