In the early 1900s, Reese, Michigan was a working-class farm town where trains stopped, flags waved, and neighbors knew each other by name. Life moved at the pace of the railroad and the harvest, with Main Street serving as both the town’s pulse and its gathering place. Through a rare set of photographs, we revisit Reese Michigan history at a time when hard work, faith, and community built something meant to last.

Early Settlement and Founding (1860s–1870s)

Reese, Michigan, traces its beginnings to the years immediately after the Civil War. The first known settlers arrived in 1865 when Mrs. Louisa Woodruff and her son built a log home in what is now the center of Reese. At that time, the area was dense forest, and early pioneer families like the Woodruffs and Starks literally camped in tents as they began clearing land. Transportation links soon spurred growth: by 1871, a plank road was opened from East Saginaw through the settlement (then known as Gates) to Watrousville, greatly improving access for wagons and stagecoaches.

A.W. Gates, a stagecoach proprietor, established a mail route along this plank road and opened a stage office and post office (named “Gates” in his honor) at a local hotel run by the Rogers family. Around the same time, basic businesses appeared – for example, Daniel Woodruff (Louisa’s son) opened the first general store in 1871, and George Melatt and Archie Scott set up a blacksmith shop. These early services signaled that a small community was taking root at the rural crossroads.

The year 1873 proved to be a turning point in Reese’s history. The Detroit and Bay City Railroad laid tracks through the settlement that year, bringing fast transportation and new opportunities. Hudson B. Blackman, a land developer, platted a new tract of land adjoining the original hamlet and named it “Reese,” in honor of Alvin H. (G.W.) Reese, the railroad superintendent who oversaw the line’s construction. With the railroad came a depot and a shift in identity – the station and post office were soon renamed Reese, supplanting the old name of Gates.

Asenath Rogers (whose family had platted the little village of Gates earlier) surveyed an additional plat in 1875, and before long, the entire settlement took on the Reese name. By 1877, just a few years after the rails arrived, Reese’s population had already swelled to over 300 residents. Contemporary accounts described Reese at that time as “the railroad and trading point for a large section of farming country,” a hub where local timber, limestone, and farm produce were gathered for shipment to larger markets.

Early businesses prospered serving the needs of farmers and travelers: for instance, Joseph Stark’s hotel (opened in 1873 at Reese and Saginaw Roads) provided lodging to newcomers and stagecoach passengers, while the Woodruff general store supplied groceries and provisions. Daily stage lines ran through Reese (connecting Saginaw to Caro), and the new depot bustled with freight and passengers moving in both directions. In short, by the late 1870s, Reese had firmly emerged from the wilderness as a small railroad village and marketplace for the surrounding agricultural region.

Village Growth and Institutional Development (1880s–1900)

During the 1880s and 1890s, Reese continued to mature, laying down the institutions and infrastructure of a permanent community. The village’s first school had humble beginnings – a local school district was organized in the 1860s, and classes initially met in a simple lumber shanty. However, by 1880, residents erected a dedicated schoolhouse to educate their children. This original Reese school building (a wooden structure) would serve the community for decades (with later expansions in 1912)

Churches also took root as the population grew. A Catholic congregation was among the earliest: in 1872, a Catholic mission church known as St. Elizabeth was established just west of town. By 1884, the parishioners famously placed the small church building on logs and moved it into Reese across the county line. With the arrival of a resident priest (Father Thomas Hennessy) in the 1880s, St. Elizabeth became the first permanent parish in the village.

The Catholic community’s presence would continue to grow, eventually warranting its own parochial school in the next century. Protestant settlers also formed congregations; for example, in 1903, local families organized Trinity Lutheran Church to serve residents between Saginaw and Caro, reflecting the German Lutheran heritage of many settlers.

By 1900, Reese was home to multiple churches and a public school, signalling a well-established community. Civic progress in Reese was marked by formal incorporation and local governance. In 1887, Reese was officially incorporated as a village, creating a village council to provide basic services and oversight. This step allowed the community to enact ordinances, improve streets, and better represent itself within Tuscola County. Village officials focused on practical needs such as maintaining roads (the old plank road evolved into a graveled highway) and public safety. Volunteer efforts led to the organization of a bucket brigade for fire protection, and later the purchase of firefighting equipment as funds allowed. The village remained small – the 1900 census recorded 416 inhabitants – but it was self-governing and proud.

Life in Reese during the late 19th century revolved around its agricultural economy and local institutions. Farmers from the surrounding Denmark Township came to town to patronize businesses like general stores, feed mills, and blacksmith shops, or to ship their grain and livestock via rail. A snapshot from the time shows Reese as a modest yet thriving prairie village: by 1890 one could find at least one hotel, a post office, a couple of churches, a school, and a handful of shops clustered near the railroad crossing – the essential framework of rural American community life was firmly in place.

Economic Activity: Farming, Railroads, and Local Enterprise

Agriculture has always been the backbone of Reese’s economy, and between 1870 and 1950, the village’s fortunes rose and fell with the cycles of farming life. The first homesteaders initially had to clear thick forests, selling timber and firewood; indeed, lumber was one of the early products shipped out on the railroad.

Once the land was cleared, farmers planted staple crops like wheat, oats, and corn. Over time, the Saginaw Valley region (which includes Reese) became known for specialized crops such as dry beans (navy beans) and sugar beets. By the early 1900s, sugar beets were a major cash crop in the area, so much so that in 1912 , local farmers each donated the proceeds from one load of sugar beets to help finance their church, and even raffled off a horse to raise money for the parish.

This anecdote illustrates the prominence of sugar beet farming and the close-knit, cooperative spirit of the Reese community. The railroads played a critical role in Reese’s economic development. With two rail lines intersecting in the village – the Michigan Central (originally the Detroit & Bay City line) running north–south, and the Port Huron & Northwestern (later part of the Pere Marquette Railway) running east–west – Reese became a convenient shipping point for farmers and merchants.

Train cars loaded with local grain, dry beans, sugar beets, and livestock routinely left Reese for markets in Detroit and Saginaw. In the early 1900s, for example, area farmers would drive their hogs and cattle into the village to be loaded on railcars bound for the stockyards in Detroit. Incoming trains, meanwhile, delivered coal, farm machinery, mail-order goods, and other supplies vital to rural life. The dual rail depot in Reese was a lively spot: it even had two separate train order signal boards (one for each railroad company) on the platform.

This indicates how both lines actively used the station and coordinated schedules in the era before electronic controls. Local manufacturing in Reese remained small-scale and agriculturally focused. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, businesses in town included a grist mill or feed mill to grind farmers’ grain, a lumber yard, and later perhaps a creamery or sugar beet dumping station (as sugar factories in nearby towns processed the beets).

By the 1920s, cooperatives or grain elevators in Reese allowed farmers to store and sell their crops more efficiently. One notable enterprise was the Reese & Tuscola Milling Company, known to be operating by the 1930s. This company likely dealt in flour, animal feed, or bean processing (reflecting the importance of those commodities to local farmers). While Reese never industrialized with large factories, its economy was sustained by these agribusinesses, the railroads, and the steady productivity of family farms in the surrounding townships.

Community Life and Notable Events

Throughout the 1870–1950 period, the people of Reese built a vibrant community life centered on family, faith, hard work, and mutual support. Notable early residents left their imprint on local history. The Woodruff family, as first settlers, not only tilled the first fields but also ran the first store, becoming providers for their neighbors. A.W. Gates, for whom the village was first named, ensured Reese was on the postal map by securing the post office and running the stage line – a critical service before the railroad.

Entrepreneurial settlers like Joseph Stark (builder of the early hotel in 1873) and the Rogers family (original plat owners and innkeepers) gave Reese its first institutions for lodging and hospitality. As the village grew, others stepped forward: James N. Taylor, for example, served as postmaster in the late 1870s and early 1880s, managing mail during Reese’s formative years.

It was not always easy – the Taylor family lost their home and possessions to a fire in 1889, a reminder of the hardships early residents faced – but the community rallied together in such times of need. Education was a source of pride and investment in Reese. The one-room school of 1880 gave way to an expanded school building in the new century. In April 1913, a dramatic event struck when a student accidentally set fire to the frame schoolhouse, burning it to the ground. Despite this setback, the village wasted no time in rebuilding; by the next year (1914), a new brick school was completed at a cost of $10,231. That sturdy schoolhouse became a center of village life, hosting classes and community gatherings for decades to come. (It survived with later additions until finally being replaced in the 1960s.) Education was not limited to public schools: Reese’s churches also contributed. Trinity Lutheran Church, soon after its founding, established a parochial grade school in 1921 to offer faith-based education to local children. St. Elizabeth’s Catholic Parish, after years of fundraising and growth, opened its own parish school in 1947, taught by the Sisters of Mercy, to serve the Catholic families of Reese.

These schools underscored the community’s commitment to educating the next generation even through difficult times like the Depression and World War. Reese experienced its share of local milestones and trials in the first half of the 20th century. The arrival of utilities and services was one gradual milestone: telephones began connecting farms and businesses in the early 1900s, and by the 1930s, electricity reached many rural homes thanks to national rural electrification efforts.

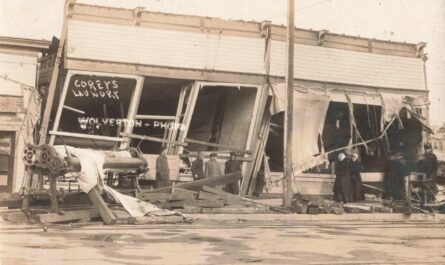

Community booster groups and fraternal organizations (such as a village improvement society, 4-H clubs, and perhaps a Masonic lodge or Grange chapter) were formed in the 1910s and 1920s, sponsoring fairs, holiday parades, and school events. These activities wove a tight social fabric in Reese. On the other hand, disasters occasionally struck. Aside from the 1913 school fire, there were periodic fires on Main Street that threatened businesses (firefighting was done by bucket brigade or a small chemical engine until a formal fire department was created later).

Weather extremes also tested the village – prairie fires in the 1870s, the harsh winter of 1880–81, or the nationwide Armistice Day Storm of 1940 would have been felt in Reese. However, residents persevered as rural Michiganders long accustomed to nature’s challenges.

Impact of National Events: Wars and the Depression

The history of Reese from 1870 to 1950 was not lived in isolation – national and regional events left their mark on this small community. Wars in particular had a profound impact. During the Spanish–American War (1898) a few local men volunteered, but it was World War I (1914–1918) that truly touched Reese: young men from the village were drafted or enlisted to fight in Europe, and the community supported them with War Bond drives, Red Cross sewing circles, and Victory Gardens at home.

A service flag hung in the window of the post office, bearing a star for each Reese man in uniform. When the war ended in 1918, Reese – like towns across America – celebrated the victory, mourned the fallen, and erected monuments or honor rolls to commemorate its veterans (some Reese families lost sons to combat or influenza that year, although exact numbers are not recorded here).

The 1920s brought a brief farm prosperity, but this boom was followed by the crushing Great Depression of the 1930s. As an agricultural community, Reese felt the Depression acutely. Crop prices for beans, corn, and sugar beets plummeted, squeezing farm incomes. Droughts in the middle of the decade added to farmers’ woes, and the nationwide bank failures in 1933 tested even the local institutions (Reese’s own bank had to navigate the state-declared “bank holiday” and subsequent reforms). Yet, the community proved resilient.

Federal New Deal programs likely provided some relief: area farmers benefited from price supports and soil conservation programs, and young men from Reese joined the Civilian Conservation Corps or WPA projects. Oral histories recall WPA crews improving local roads and drainage ditches in Tuscola County, which would have helped Reese’s farmers by upgrading the rural infrastructure. Despite hard times, the village’s population held steady through the 1930s (roughly 490 people in 1930, dipping only slightly and then rebounding to 569 by 1940).

Neighbors helped one another with “barn raisings” and shared equipment when individual families couldn’t afford repairs. The churches and school also served as safety nets, organizing charity drives and free lunches for children. By the late 1930s, as the Depression eased, Reese’s farm economy began to recover alongside rising commodity prices. World War II (1941–1945) brought new changes and challenges. Dozens of local men and women served in the armed forces, stationed in places as far-flung as the Pacific and Europe.

Several Gold Star families in Reese mourned sons who did not return from battle. On the home front, Reese’s citizens participated in gas and tire rationing. They held scrap metal drives – one local story tells of schoolchildren gathering scrap iron and old rubber in 1942 to contribute to the war effort. Farmers in the Reese area stepped up production of food crops to feed troops and civilians, often coping with labor shortages as hired hands went off to war.

The sugar beet harvest, for instance, relied on German prisoners-of-war from a nearby POW camp in 1944 to alleviate the manpower shortage (a common arrangement in Michigan’s Thumb region). When victory came in 1945, Reese joined the national jubilation: church bells rang and a celebratory parade was held on Saginaw Street, honoring the returning veterans. In the post-war years, Reese saw renewed growth and optimism. Young veterans came home, some starting new families (the baby boom was soon underway) and others taking advantage of the GI Bill to buy farms or start businesses. By 1950, the village population had risen to 632 people, its highest to date, indicating modest growth as the economy flourished after WWII.

Postwar Outlook by 1950

As of 1950, Reese was a stable and close-knit small town poised between its rustic past and a more modern future. The community still centered on agriculture – fields of corn, navy beans, soybeans, and sugar beets stretched in every direction – and farm families continued to depend on institutions built in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, from the grain elevator by the railroad tracks to the churches at the heart of the village.

Yet, signs of change were evident. Improved highways (like M-81, which follows the old plank road route) and personal automobiles meant residents were less isolated than before; one could drive to Saginaw or Bay City for shopping or jobs, a trend that would accelerate in the coming decades. The railroads that had given birth to Reese were still operating in 1950 – in fact, the Pere Marquette Railway had been absorbed into the C&O Railroad in 1947– and trains continued to stop for grain shipments. However, the era of passenger service was waning.

Within the village, new housing construction was starting to pick up after the war, and civic improvements like a village water tower and modern electric street lights were on the horizon. Reese’s identity from 1870 to 1950 was shaped by the enterprising spirit of its people and the ebb and flow of larger historical forces. The town began as a tiny frontier outpost on a plank road and grew into a vital rural community thanks to the railroad boom of the 1870s.

Reese Michigan weathered fires, economic panics, and the Great Depression, all while maintaining its character as a farm town grounded in cooperation and hard work. Key developments – the coming of the rail lines, the founding of schools and churches, and the incorporation of the village – provided a framework for growth and social life. Through World War hardships and peacetime progress, Reese’s residents continually adapted, supporting each other and embracing civic projects from building new schools to paving streets.

By 1950, the village of Reese had a rich history spanning four generations, with stories of pioneers and immigrants, prosperous harvests and challenging winters, all contributing to the make up of this Michigan community’s heritage. The decades to follow would bring further change, but the period from 1870 to 1950 had firmly established Reese as a lasting hometown for its citizens – a town built on the railroad, sustained by the soil, and strengthened by the shared experiences of its people.

Sources

“Reese, Michigan.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, last modified 30 Apr. 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reese,_Michigan.

United States Census Bureau. “1950 United States Federal Census.” National Archives and Records Administration, https://www.archives.gov/research/census/1950.

History of Tuscola and Bay Counties, Michigan: With Illustrations and Biographical Sketches of Their Prominent Men and Pioneers. Chicago: H.R. Page & Co., 1883. Available via HathiTrust Digital Library: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=loc.ark:/13960/t0gt6k02x&view=1up&seq=9.

St. Elizabeth Catholic Church. History of St. Elizabeth Parish: Reese, Michigan. Parish Archive Booklet, ca. 1972. Excerpts available via parish historical summaries: https://www.aod.org/parishes/st-elizabeth-catholic-church-reese.

Trinity Lutheran Church, Reese. 100th Anniversary Booklet: 1903–2003. Internal Publication. Select references available via church history site: https://trinityreese.org/about.

NASA Earth Observatory. “Field Patterns near Reese, Michigan.” Earth Observatory Feature Images, NASA, 24 Sept. 2006, https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/17208/field-patterns-near-reese-michigan.

Michiganrailroads.com. “Reese, MI.” Michigan Railroad History, 2024, https://www.michiganrailroads.com/stations-locations/91-tuscola-county-79/1696-reese-mi.

Tuscola County Clerk. Village of Reese Incorporation Records, 1887. Abstracted data and charter summary available at: https://www.tuscolacounty.org/clerk/.

Michigan Bean Commission. “History of the Michigan Dry Bean Industry.” MichiganBean.org, https://www.michiganbean.org/about.