The St. Joseph Indian Trail was an ancient major Native American route that traversed the southern portion of Michigan. Originating near the mouth of the St. Joseph River, it continued eastward, terminating near Ann Arbor and connecting with the other major trail systems along the Straits of Detroit.

Table of Contents

The St. Joseph Indian Trail roughly paralleled the famous Great Sauk Trail, which traversed Michigan along a route further south. The trail and the name morphed with the times, as the path was also called Old Joe Trail and Route du Sieur de la Salle. After Michigan became a state, the trail was improved and denoted as Territorial Road, one of Michigan’s first public highways. The route opened the “second tier of southern counties” north of Indiana and Ohio and helped to foster settlement in Southwestern Michigan. Today, the ancient Native American pathway is in bits and pieces of Michigan Avenue, U.S. 12, and vast swaths of I-94.

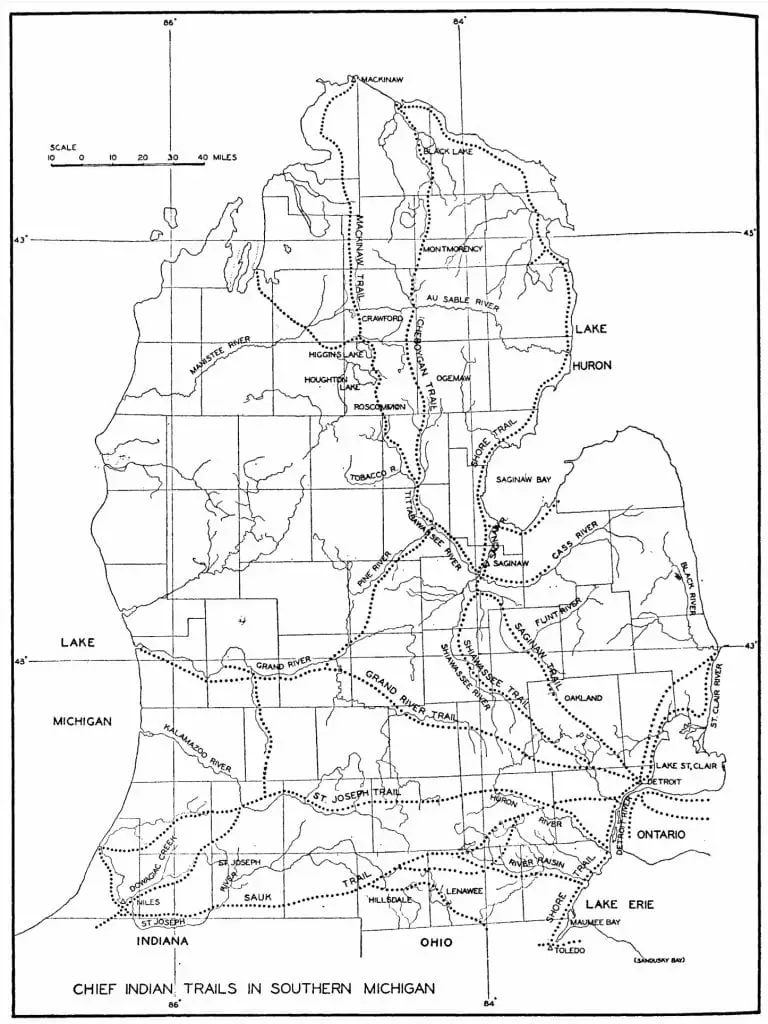

Key Aspects of Michigan’s Indian Trails

The early European settlers remarked about the ancient trails with some key characteristics. They were narrow rutted paths, sometimes 12 to 18 inches wide, as the Native Americans walked single file to hide their numbers. The paths typically crossed on high ground and ridgelines to avoid the standing water of swamps and seasonal floodplains. When a trail crossed a river, it was expected that stepping stones were placed to denote a shallow area and assist in its crossing. Finally, these paths converged in the major native settlement areas of Saginaw, Niles, Detroit, and Ann Arbor.

Some parts of the trail were denoted as water trails. The St. Joseph trail terminated east of Ann Arbor, and travelers had the option of continuing on the Huron River toward Detroit. Likewise, the SandRidge trail on the western Thumb has a crossing at Oak Point across Saginaw Bay via Charity Island to the mouth of the Au Sable, a prime fishing area.

The legend of the St. Joseph Trail and the French Explorer LaSalle

In August 1679, La Salle finished the construction of the ship Le Griffon. This was the first European-designed ship to be constructed on the Great Lakes. While the exact measurement is unknown, the double-masted ship was believed to be up to 40 feet long with a wide 15-foot beam. Carrying seven cannons and a cargo capacity of nearly 45 tons, this ship would have been viewed as a monster when it was launched on the upper Niagara River in early August.

La Salle and his party’s first mission of Le Griffon was to trade in the Upper Great Lakes. The Griffon sailed up Lake Erie through the Straights of Detroit. On August 9th in Detroit, he met up with his lieutenant Henri De Tonti, who joined him for the voyage up Lake Huron. On August 27th, they arrived at Fort Michilimackinac to deliver 1,300 Livres worth of trade goods at the southwestern trading post.

La Salle and De Tonti Travel Separately

At the end of August, La Salle and Tonti parted ways. Tonti was assigned to round up deserters encamped at Sault Ste Marie’s major trading post. LaSalle sailed to Green Bay, Wisconsin. Here, the Le Griffon left for Niagara with a load of furs, and LaSalle traveled via canoe along the shore of Lake Michigan to seek a water route to the Mississippi. He continued with his men in canoes down the lake’s western coast, rounding the southern end to the mouth of the Miami River. A small stockade was built, which they called Fort Miami. Tonti left Sault Ste. Marie rendezvous with La Salle in early October after almost 38 days of canoe travel down Lake Michigan, likely along the eastern shore.

As Spring approached in Southwestern Michigan, on March 1st, La Salle left Tonti in charge of the new post and headed east overland on the St Joseph Trail in search of news of the Griffon, which he assumed was wintering near Detroit.

Normally, travelers would head east on the well-known and established Sauk Trail. However, it was a dangerous time of conflict due to the hostile actions of the Iroquois, who were determined to expand their trapping territory for furs for trade with the French. This made travel on the Sauk Trail a dangerous ordeal. So LaSalle proceeded on a lesser-known trail that headed east to avoid coming into contact with the Iroquois.

Little did LaSalle know, but the Griffon had sunk near Green Bay, Wisconsin, with all hands. The wreck of the Griffon has never been found. LaSalle and five men took a month to walk across Michigan to Niagara. They were considered the first Europeans to traverse the interior of Michigan.

The Indian Trail Evolves

The area around the St. Joseph Valley was rich with animals and natural resources. As a result, several tribes, including Miami and Potawatomi, occupied the region until they were forcibly removed in the 1840s. The area was also a well-known rendezvous point for those traveling to and from the Mississippi via the Kankakee River, and the Fort Wayne and Sauk Indian trails converged in this area.

After the voyages of La Salle and De Tonti, the St. Joseph Trail remains a single path through southern Michigan’s dense forests and prairies for over 150 years. In 1805, Michigan became a territory, and for the next 30 years, the territorial government’s priorities were to create a system of territorial roads to assist in the state’s settlement. By 1831, a public act was passed:

“to layout and establish a territorial road, commencing at or near the inn of Timothy S. Sheldon, on the Chicago road, in the township of Plymouth, and running thence through the village of Ann Arbor west to the mouth of St. Joseph’s river…the road would become a public highway.”

Laws of the Territory of Michigan V. III

A few years later, in 1834, the US government stepped in and declared Territorial Road a federal highway and set aside $20,000 for further improvements.

The Era of the Corduroy Road

When the Territorial road was first built from Plymouth to St. Joseph, a portion of the road was ‘corduroy.’ which means wood logs placed firmly together in a fashion resembling the ribs in corduroy fabric. This would keep the roadbed intact during wet and winter weather. Even today, construction crews may encounter the embedded logs of a portion of a corduroy road.

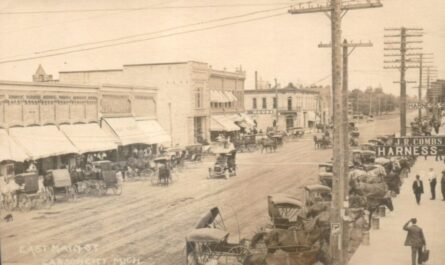

Traveling on the St. Joseph Trail Today

If you travel across Michigan on I-94, you’re cruising along much of the same path as the original St. Joseph Trail and Territorial Road. However, further west, the old trail diverges south and shares the route with US 12 and Michigan Avenue.

St. Joseph Indian Trail Map

Historical Markers About The St. Joseph Trail Near Niles, Michigan

The St. Joseph Trail, used for centuries by Native Americans and European settlers, played a crucial role in the development of Niles, Michigan. The trail follows the St. Joseph River and was a primary route for the Miami and Potawatomi tribes before European exploration. French traders like Joseph Bertrand established trading posts along the river, while missionaries like Isaac McCoy set up missions. The area’s markers commemorate these early interactions, settlements, and the significant historical events that shaped the region.

Table of Historical Markers Covering the St. Joseph Indian Trail

| Name of Marker | Location | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Niles – A Transportation Center | Niles, Berrien County, MI | Highlights the importance of the St. Joseph River and the Sauk Trail (now US 12) as key transportation routes for Native Americans, French voyagers, and settlers. |

| The Rivers and the Native Americans | Niles, Berrien County, MI | Describes the history of the Miami and Potawatomi tribes in the valley, their villages, and the role of the river in their culture and livelihood. |

| The St. Joseph Indian Trail | Jackson, Michigan | Here the St. Joseph Indian Trail crossed Jackson’s first town square in 1830 |

These markers provide a comprehensive overview of the region’s diverse history, from native settlements to European colonization. For more detailed information, you can explore the Historical Marker Database.

Sources of the St. Joseph Trail

- Peek through time: St. Joseph Trail played an important part in the settlement of Jackson- Mlive https://www.mlive.com/living/jackson/index.ssf/2010/10/peek_through_time_st_joseph_tr.html

- Transportation in Michigan History, Indians Started Road from Footpath to Freeways By Philip P. Mason 1987

- Indians of Washtenaw County, Michigan, by W. B. Hinsdale, 1927

- E. B. Osler, “TONTY, HENRI,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 2, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 30, 2019, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/tonty_henri_2E.html.

- Early St. Joseph County History https://historymuseumsb.org

I thought the Corderoy Road era in Michigan started in the early 21st Century. Ha!

Nice work Mr. Hardy