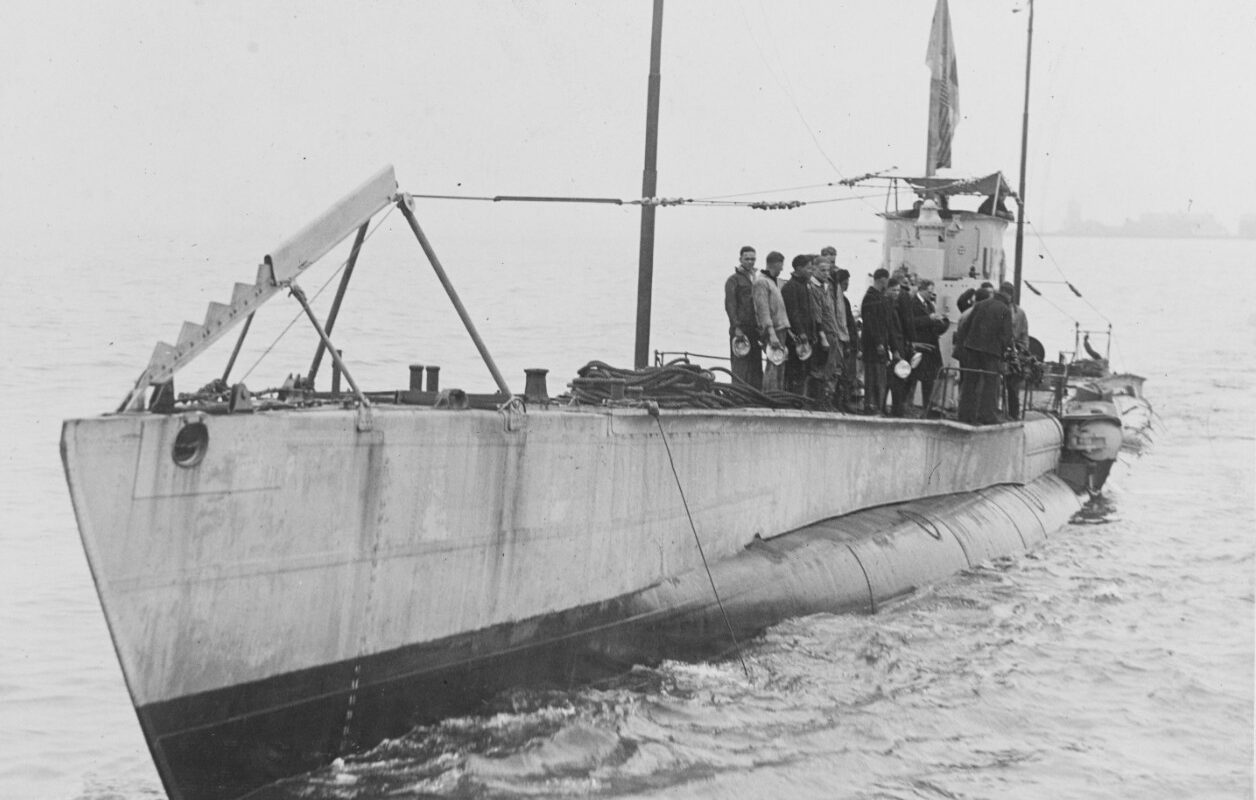

In the summer of 1919, a captured German submarine made headlines across the Great Lakes. UC-97 (often reported as U-97) had been surrendered at war’s end and was brought to the United States for a patriotic bond and recruiting drive. After a New York refit, the 185-foot minelayer steamed north under escort toward the lakes. On May 16, the Halifax Herald reported that German U-Boat UC-97 “arrived here Friday on her way from New York to the Great Lakes” under U.S. Navy escort. By late June, it reached Detroit and kicked off a port-by-port tour that drew huge crowds. As a Navy history notes, UC-97 was “the biggest sensation to hit the Great Lakes” in 1919 – “hundreds of thousands of people, in virtually every port in the Great Lakes (except for Lake Superior)” lined up to catch a glimpse. The German crew’s gray sub (German slate paint replaced by U.S. Navy gray, but still flying the German ensign beneath Old Glory) became a living exhibit of the war at home.

Detroit Homecoming Celebration

Detroit was the first major stop. On Sunday afternoon, June 29, 1919, the U-boat “nosed up the Detroit River and tied up at the foot of Randolph Street”, alongside two U.S. subchasers. Detroit officials quickly made her the centerpiece of Independence Day festivities. Returning soldiers of the 339th Infantry, who had endured Arctic service in Russia, were invited aboard. Newspapers excitedly reported that the troops “will have a chance to tread the decks of the German submarine U.C. 97” as part of the July 4 welcome at Belle Isle. City and federal authorities even scheduled open-deck tours for the public: within days, thousands of Detroiters queued to go below the decks of the once-feared enemy vessel.

The sub’s combat record was highlighted in the press. Naval accounts noted that UC-97 had been credited with sinking seven Allied ships during the war. Lt. R. H. Dixon of the U.S. Navy, in charge of the escort, described it as “menacing in aspect.” He quipped that the gray submarine “looks her name, the pirate of the sea,” even though she had been “shorn of her teeth” (all torpedoes, mines, and ammunition were removed before the tour). Still, children and families marveled at the huge surfaced hull and its deck gun – a far cry from anything most Midwesterners had ever seen. The Detroit stay lasted about a week; records show UC-97 remained tied up downtown through July 5, with Army and Navy officers inspecting her before she resumed the voyage.

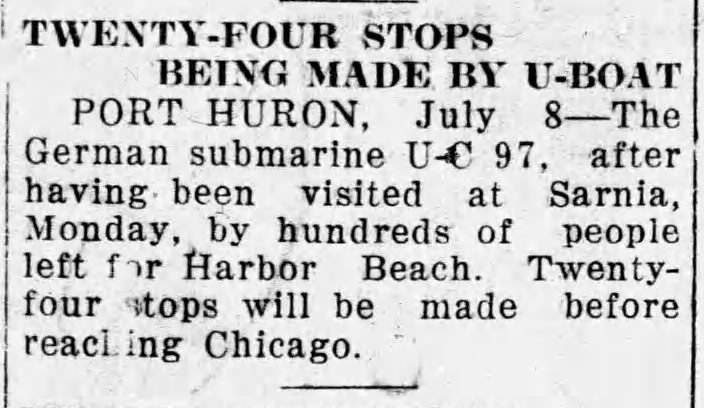

German U-Boat UC-97 Stops In Canada and up the Lake Huron Shore

After Detroit, UC-97 made dozens of additional stops. Port Huron readers learned on July 8 that the sub had just left Sarnia, Ontario, after being toured “by hundreds of people,” and was bound for Harbor Beach. The paper note,d “twenty-four stops will be made before reaching Chicago.”

Naval records confirm the wide itinerary: the submarine visited nearly every sizable port on Lakes Ontario, Erie, Huron and Michigan before its tour ended in Chicago. In fact, UC-97 became “the first submarine of any nation to sail on the Great Lakes” as it transited the St. Lawrence Seaway and the Welland Canal. By mid-August, the vessel was set to dock at the Great Lakes Naval Station (near Chicago).

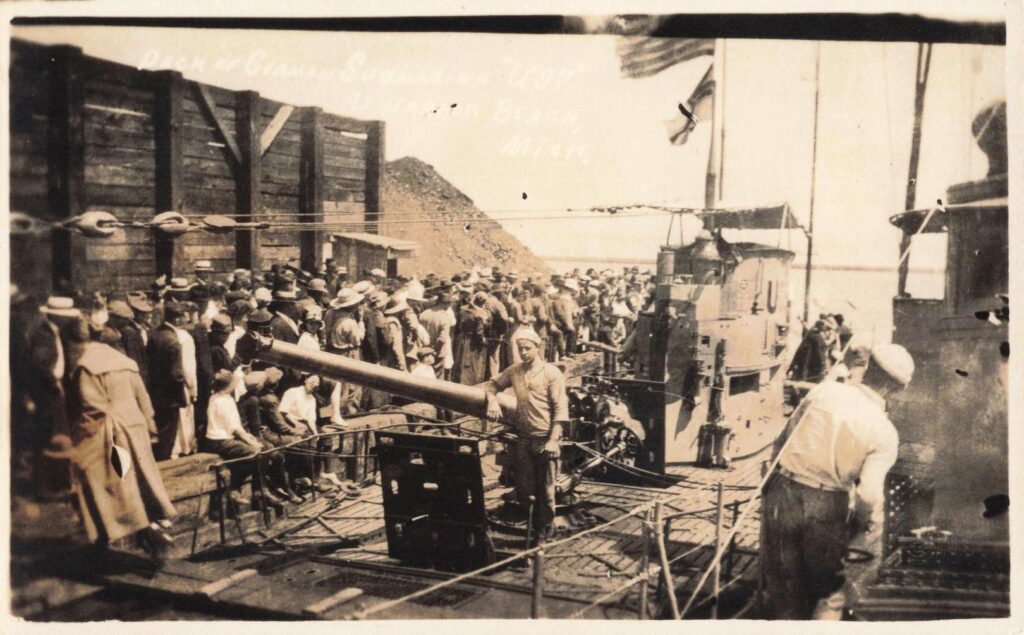

Harbor Beach Spectacle of German U-Boat UC-97

From Detroit, the U-boat headed northeast into Lake Huron. On July 9, 1919, it steamed into tiny Harbor Beach, Michigan (population only a few hundred). The local newspaper urged everyone in “the Thumb” region to come out. A July 3 report announced that Congressman Frank Cramton had confirmed the visit: the “captured German submarine U 97…will visit Harbor Beach next Wednesday, July 9.”

The Harbor Beach Board of Commerce invited “all the Thumb town people” to see the sub, arguing that for most, it was a once-in-a-lifetime chance. The paper noted that comparatively few civilians in the area “have ever seen one of these wasps of the sea,” so “it will be worth going miles to see” the strange craft. Hundreds of locals did just that. Despite its simplicity, Harbor Beach rolled out the red carpet – businesses closed, and boats gathered as the grey U-boat quietly tied up for the morning. By afternoon, she continued north, her deck swarming with eager visitors.

The German U-Boat UC-97 Was Loved to Death

Heavy crowds and mechanical strain forced some changes. Plans to reach Lake Superior were canceled due to engine wear and the challenges of hosting massive throngs. A Navy historian later reported that nearly “5,000 people would tour” UC-97 each day at the height of the tour“. Still, the overall campaign was deemed a public relations triumph. As one account put it, the cruise “was considered a huge success, and one of the few bright spots of an otherwise dismal 1919”. It raised millions in war bonds and gave thousands a tangible connection to the end of the conflict.

After the summer tour concluded in Chicago, UC-97 saw no further service. It lay at the Great Lakes Station until June 1921.

The Sinking and Forgotten Legacy of German U-Boat UC-97

By 1920, the Harbor Beach submarine and its sister ships were fading from public memory. After the whirlwind Great Lakes tour, UC-97 sat idle, a stripped-down shell moored on the Chicago River. The U.S. Navy had already scavenged every piece of technical value—engines, periscopes, and pumps were distributed to various Navy yards, labs, and defense contractors for study.

The fate of UC-97 differed from its peers. On June 7, 1921, unable to journey far, the submarine was towed into Lake Michigan. The USS Wilmette (IX-29), herself a converted passenger ferry (once the Eastland, infamous for the 1915 disaster that killed 844 people in Chicago), was assigned to sink the old warship as a Naval Reserve target.

The event was treated with pageantry. The first shell was fired by Gunner’s Mate J. O. Sabin, credited with firing the U.S. Navy’s first Atlantic shot in World War I. The last was fired by Gunner’s Mate A. H. Anderson, who had launched the Navy’s first torpedo attack against a U-boat. After 13 hits from 18 four-inch shells, UC-97 slipped beneath the waves of Lake Michigan—its final duty completed.

For decades, German U-Boat UC-97 was forgotten. Even the Navy was skeptical when researchers in the 1960s sought proof of the German U-boats’ existence on the Great Lakes. Multiple searches failed, and the submarine gained a reputation as a ghost wreck. It wasn’t until 1992 that A and T Recovery finally located UC-97. Although the precise site remains undisclosed, the wreck, resting within sight of Chicago’s skyline, stands as a silent relic of an extraordinary chapter in Michigan’s maritime history.

Sources:

Historical newspaper accounts and U.S. Navy records of UC-97’s 1919 tour

MLA Citations:

- Associated Press. “Hun Submarine to Sail on the Lakes.” The Halifax Herald, 16 May 1919.

- “German Submarine at Harbor Beach.” Harbor Beach Times, July 1919.

- “German Sub Will Make a Visit Here.” The News-Palladium (Benton Harbor, MI), July 1919.

- “German U-Boat Arrives Here.” Detroit Free Press, 30 June 1919.

- “German Sub Will Make a Visit at St. Joseph.” The News-Palladium (Benton Harbor, MI), July 1919.

- “Hun Submarine to Be Feature of Big Welcome to 339th.” Detroit Free Press, 28 June 1919.

- “Twenty-Four Stops Being Made by U-Boat.” Port Huron Times Herald, 8 July 1919.

- U.S. Navy. H-031-1: German Submarine UC-97 on the Great Lakes, 1919. Naval History and Heritage Command, updated 13 June 2019, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/u/uc-97.html.

- Weir, Gary E. Rising Tide: The Untold Story of the Russian Submarines That Fought the Cold War. Basic Books, 2004 (background context on U.S. Navy procedures for captured submarines).

- A and T Recovery. “The Wreck of UC-97.” A and T Recovery, 1992, http://www.atrecovery.com/uc97.html.