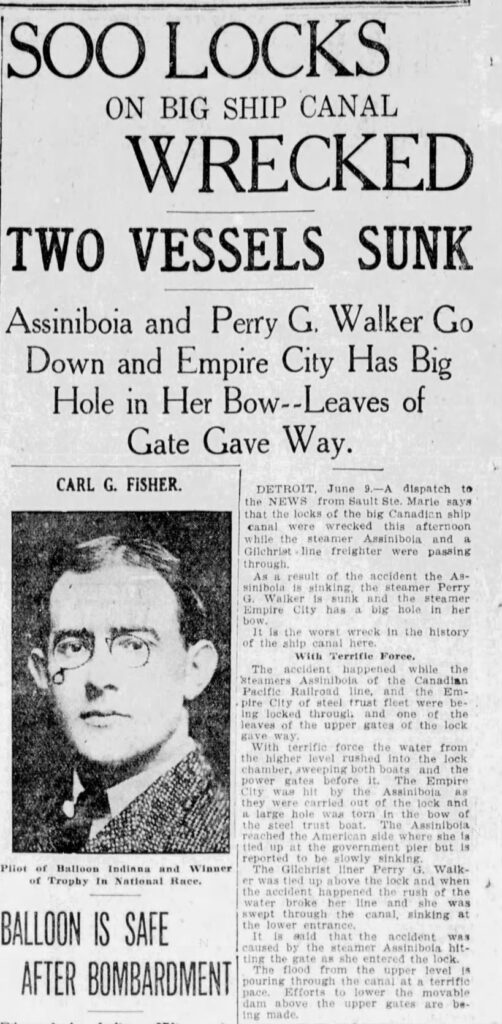

On a quiet afternoon in June 1909, disaster struck at the heart of North America’s shipping network. The Canadian Soo Locks at Sault Ste. Marie—one of the busiest passages for commercial freighters on the Great Lakes—suffered a sudden mechanical failure. Within minutes, four ships were caught in a torrent of water. Two sank. Others were severely damaged. The locks were left in ruins, and commercial shipping on the Great Lakes came to a standstill.

While largely forgotten today, the Soo Locks disaster exposed a critical weakness in North America’s industrial infrastructure. This blog post revisits that moment in Michigan’s maritime history when a single lock gate failure turned into an international supply chain crisis—and forced lasting changes to the way freight moves through the Great Lakes.

Table of Contents

A Sudden Catastrophe at the Canadian Soo Locks

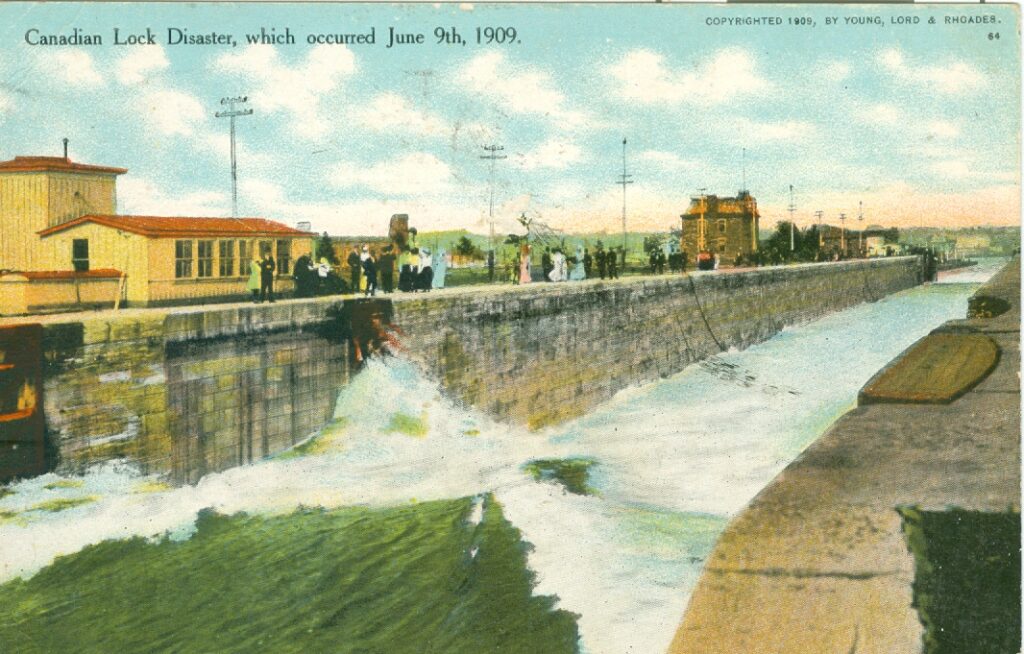

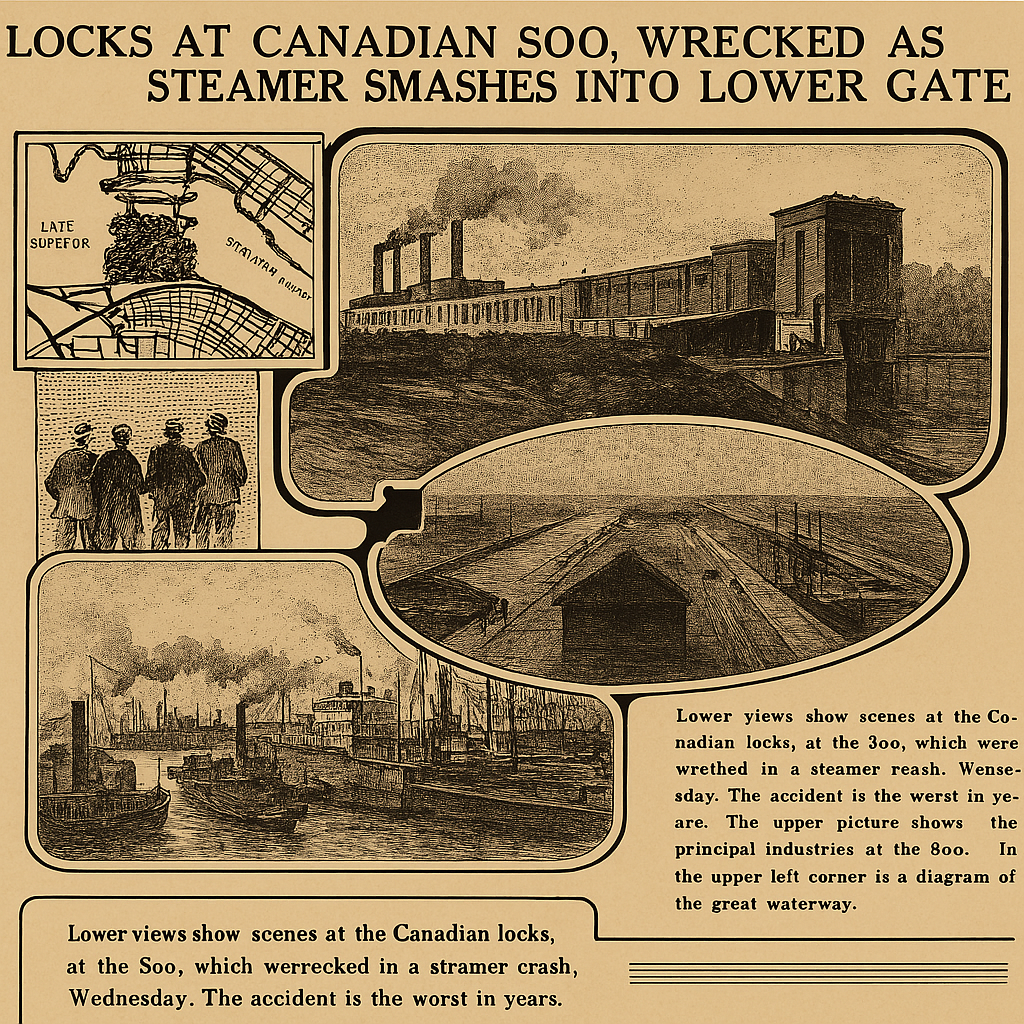

On the afternoon of June 9, 1909, a mechanical failure at the Canadian Soo Locks in Sault Ste. Marie triggered one of the worst maritime infrastructure accidents in Great Lakes history. Four ships were caught in the torrent. Two sank. The locks themselves—vital to North American trade—were torn apart.

The incident stopped traffic cold on one of the busiest freshwater shipping corridors in the world and exposed just how vulnerable the region’s economy was to a single point of failure.

What Happened on June 9, 1909?

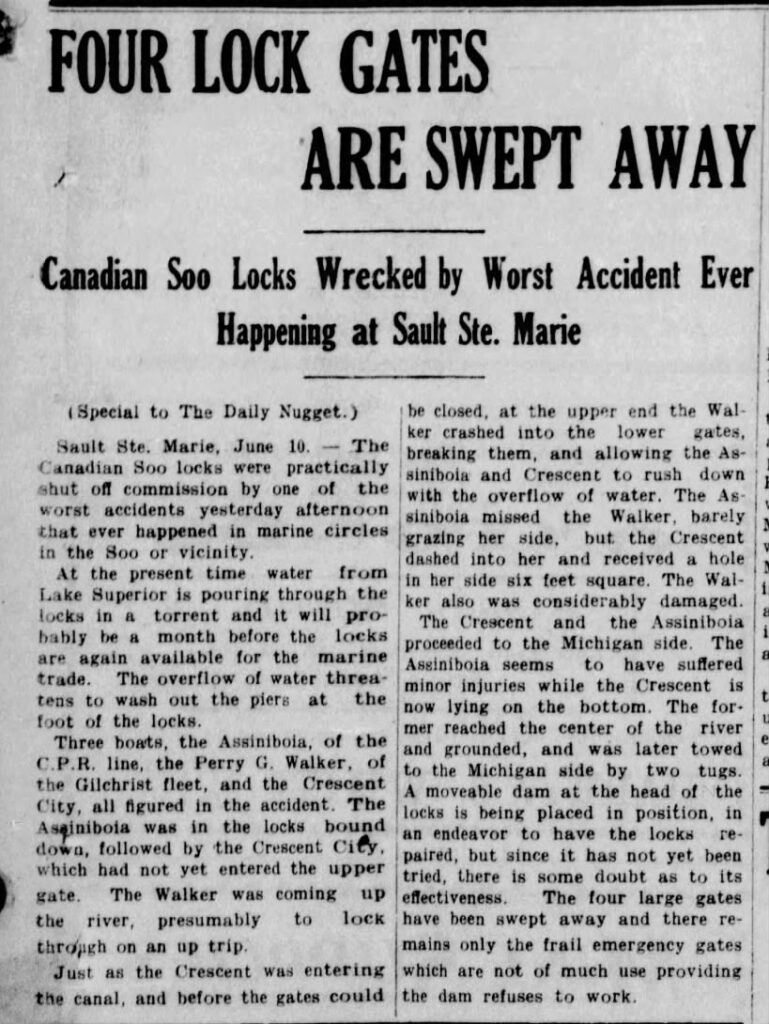

According to contemporary accounts from the Detroit Free Press and The Daily Nugget of North Bay, Ontario, the accident began when the Canadian Pacific steamer Assiniboia entered the Canadian lock chamber alongside the Crescent City, a steel freighter. At the same time, the Perry G. Walker was heading upstream toward the lock.

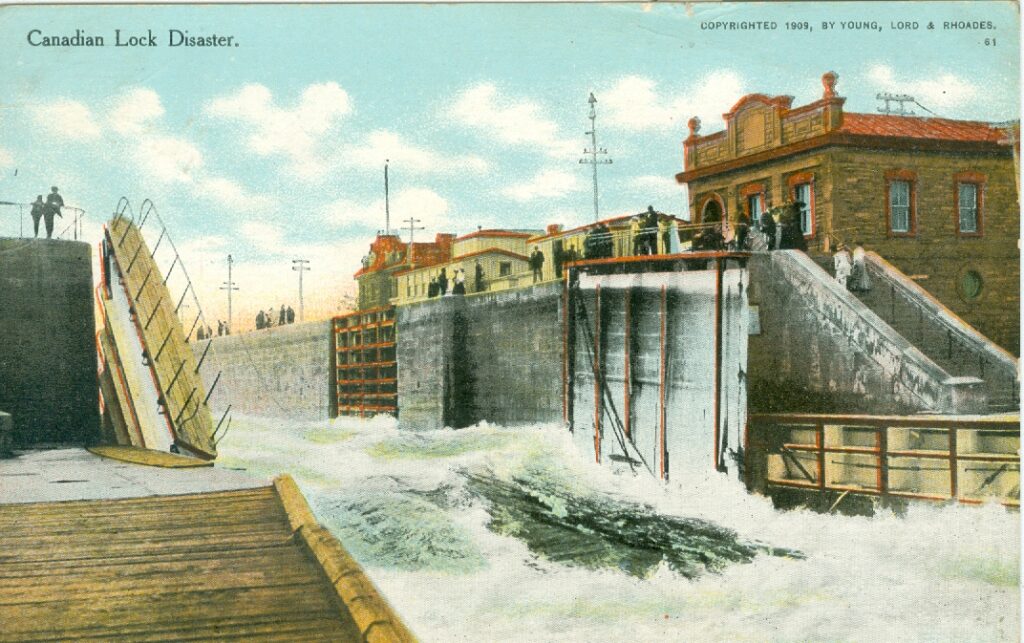

Suddenly, a leaf of the upper lock gate gave way. Water from the higher level of the canal surged into the chamber with tremendous force.

- The Empire City, which had just exited the lock, was struck by the surge. Her bow was punctured, but she remained afloat.

- The Perry G. Walker was pulled backward and sank at the lower entrance.

- The Crescent City was holed in her side and sank in the middle of the canal.

- The Assiniboia made it to the American side but was heavily damaged and slowly sinking.

Four lock gates were torn from their mounts and swept downstream. Officials initially suggested that the Assiniboia may have struck the gate while entering, though no official cause was confirmed.

A Wall of Water and a System Overwhelmed

As the gates failed, water from the upper level continued to pour into the canal. Emergency gates and backup systems were not designed to handle this volume. The result was a flood so strong it threatened to wash out the piers at the foot of the locks.

Canadian officials scrambled to install temporary dams to stop the torrent, but they were untested and of uncertain strength. For weeks, water continued to surge uncontrolled through the canal system.

The locks were effectively shut down.

The Economic Fallout

The Soo Locks, both American and Canadian, were vital to commerce. Iron ore from the mines of Minnesota and the Upper Peninsula moved through these narrow channels to reach steel mills in Pittsburgh and Detroit. Grain and coal shipments relied on the same route.

With the Canadian system offline, all pressure shifted to the U.S.-operated Poe Lock. Within days, hundreds of ships were either stuck in port or idling near the St. Marys River.

Factories across the Midwest felt the disruption. Iron ore deliveries were delayed. Coal shipments missed their windows. For a time, the economic engine of the industrial Great Lakes sputtered.

Recovery Was Swift—and Remarkable

Despite the scale of the disaster, the response was fast and effective. Crews activated a swing dam, a massive pivoting bridge designed to slow the water and stabilize the canal. This move allowed the lock chamber to be drained and repair work to begin almost immediately.

- The Assiniboia was patched and underway later that same day.

- The Perry G. Walker was raised and operational within three days.

- The Crescent City, which had sunk near the center of the channel, was raised, repaired, and sailing again in less than a week.

The Canadian lock was fully restored and reopened to commercial traffic through coordinated repair efforts within 12 days.

A Ghost of the Past in Echo Bay

Decades later, during a low water period on Lake Huron, a large metal structure was discovered on a sandbar near Echo Bay, not far from the bridge. Many believe it to be one of the original lock gates torn loose in the 1909 disaster. However, no official confirmation was ever made. The site remains unmarked, and the object remains curious for maritime historians and residents.

Aftermath and Long-Term Impact

The damage forced governments and shipping companies to rethink the system’s fragility.

The incident accelerated efforts to modernize and expand the lock systems on both sides of the river. Over the next decade, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers would oversee the construction of upgraded locks capable of handling the increasingly massive freighters of the Great Lakes fleet.

The accident also led to deeper U.S. investment in maritime infrastructure resilience—a conversation that continues today.

Could It Happen Again?

Yep—and the stakes would be even higher.

A 2016 U.S. Department of Homeland Security study estimated that a complete six-month shutdown of the Soo Locks today could cost the U.S. economy over $1.1 trillion and halt more than 10 million jobs across sectors that rely on Great Lakes shipping.

The report also warned that most of the nation’s iron ore still passes through one lock: the Poe Lock. A failure like the one in 1909 could trigger a national supply chain emergency.

A Forgotten Maritime Crisis

The 1909 Canadian Soo Locks failure has largely been forgotten outside of shipping circles. Yet it remains a clear example of how infrastructure failures can ripple across industries and borders.

We almost take it for granted as we watch freighters moving through Sault Ste. Marie—many of them longer than football fields and loaded with millions in cargo—it’s worth remembering that this system once came to a crashing halt in a matter of seconds.