In September 1837, Indian agent Henry Rowe Schoolcraft produced a detailed manuscript map titled “A Map of the Acting Superintendency of Michigan.” Created at “Michilimackinac” (an old name for Mackinac) just months after Michigan gained statehood, the map documents the region’s Indigenous nations, U.S. Indian agency posts, military forts, and newly established Native reservations?.

It includes a table listing tribal bands and their estimated populations, reflecting the situation after the pivotal 1836 treaty that ceded vast tracts of Anishinaabe (Odawa/Ottawa and Ojibwe/Chippewa) land to the United States?

Below, we break down the map’s insights by region – Upper Peninsula, Sault Ste. Marie, Lower Peninsula, and Detroit – highlighting the Native communities, U.S. government presence, color-coded treaty areas, and historical names found on this 1837 snapshot of Michigan.

Upper Peninsula: Lake Superior Ojibwe Lands and New Boundaries

Upper Peninsula detail from Schoolcraft’s 1837 map, showing Ojibwe (Chippewa) areas along Lake Superior and color-shaded reservation lands under recent treaties. The western and central Upper Peninsula in 1837 remained largely Ojibwe territory. At that time, much of this region had not yet been ceded to the U.S., aside from the eastern portion granted in the 1836 treaty?.

The map’s coloring highlights this divide: eastern UP areas (around St. Mary’s River and Drummond Island) are shaded to indicate newly created Indian reservations or ceded lands, while the far western UP is left unshaded to show it was still under Indigenous control in 1837?.

Schoolcraft labels several Ojibwe bands along Lake Superior’s shore. For example, the Keweenaw Bay area (near modern L’Anse) is marked with an Ojibwe settlement – an area sometimes called “Ance Kewaiwenon” in period documents – reflecting a significant Lake Superior Chippewa community there. Farther east, Grand Island and the shores near “Monomonee River” (Menominee River) are noted as Chippewa hunting grounds, though the Menominee people (in adjacent Wisconsin Territory) also ranged nearby. The map uses some outdated names: Lake Superior is straightforward, but the term “Michilimackinac” is used broadly for the Straits region, and the newly formed “W. Wisconsin Territory” is labeled to the west, underscoring the recent reorganization of geography after Michigan Territory’s split?.

By 1837, the U.S. presence in the Upper Peninsula was minimal but strategic. Fort Brady at Sault Ste. Marie (established 1822) is marked on the map, represented by a small square icon near the St. Mary’s River. This frontier fort had been built to guard the international border and deter British influence in the fur trade era?.

To the south on Mackinac Island (at the tip of the Lower Peninsula but influencing the UP), Fort Mackinac is also indicated, maintaining American control over the vital Straits of Mackinac. No large settler towns existed in the UP yet; instead, the map emphasizes Native domains and a few agency or trading posts. Overall, the Upper Peninsula section of the map illustrates a vast Ojibwe homeland dotted with a handful of U.S. outposts. It conveys that, apart from the ceded strip in the east, this was still an Indigenous-controlled landscape in 1837, with boundaries of the 1836 cession drawn in pencil and color to show where U.S. jurisdiction had just begun to extend.

Sault Ste. Marie: Ojibwe Hub and Agency Center

Sault Ste. Marie, at the northeastern corner of the Upper Peninsula, receives special focus on Schoolcraft’s map. This area – called Baawitigong in Ojibwe, meaning “the place of the rapids” – was a major Ojibwe (Chippewa) settlement spanning both the Michigan and Canadian sides of the St. Mary’s River. On the U.S. side, Schoolcraft denotes the “Chippeway of Sault Ste. Marie” and likely lists their population in his table (the Sault band numbered several hundred people at least). Indeed, his 1837 map’s population table “reported population for the [various] bands along with 1836 reservation locations” in Michigan?.

Sault Ste. Marie’s Ojibwe residents appear among the highest numbers; one quarter of all Native people in the 1836 cession area were the bands of Little Traverse Bay and Beaver Island in the Lower Peninsula, with the Sault’s Chippewas also forming a significant share? (this underscores Sault Ste. Marie’s importance, although exact figures for the Sault band are in the map’s table).

The Sault was also the site of a U.S. Indian Agency until 1833. Schoolcraft himself had served as the Indian Agent here, operating out of a federal agency house along the river. By 1837 the main agency had moved to Mackinac, but the map still marks the agency presence at Sault Ste. Marie – a small symbol and label (“Agency”) near Fort Brady. The American Fur Company’s post is likely noted as well, as Sault Ste. Marie was a key fur trade location where Indigenous people traded goods and received annuity payments. The map’s legend uses a distinct symbol (possibly a flag or block) to denote agency offices; one appears at Sault and another at Mackinac Island?

In addition to Fort Brady (which is explicitly labeled on the map at the Sault?, the river’s international boundary is implicitly present. Although not heavily emphasized, this was the U.S.-Canada line per the 1814 Treaty of Ghent. Some Ojibwe families moved freely across the border, and in coming years many at the Sault would consider relocating to Ontario to avoid American pressures. The map, however, is drawn from an American administrative perspective: it shows Sault Ste. Marie as a hub of U.S. Indian affairs in the region (Schoolcraft even penned the map while at “Michilimackinac,” acting as Michigan’s Superintendent of Indian Affairs)?

Notably, Schoolcraft’s annotations around Sault Ste. Marie include references to local features and possibly missionary influence (a mission to the Ojibwe existed at the time). Any outdated terminology here is slight – the French name Sault Ste. Marie itself dates to the 17th century and remains in use. But the map labels the location of the “Old Fort Brady” and the agency, hinting at changes underway. By highlighting the Sault band’s population and the U.S. facilities, the map captures this town as the crossroads of Native and federal presence on the Great Lakes frontier in 1837.

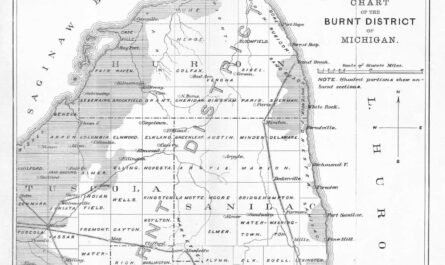

Lower Peninsula: Ottawa Villages, Potawatomi Lands, and New Reservations

In the Lower Peninsula, Schoolcraft’s map charts a patchwork of Ottawa (Odawa) and Chippewa communities across northern and central Michigan and notes the diminishing Potawatomi presence in the south. The 1836 treaty had just forced a massive land cession in the northwestern Lower Peninsula, so the map pays particular attention to that area. Large swaths of Emmet, Charlevoix, and Grand Traverse regions are tinted in yellow on the map, signifying Indian reservation lands set aside within the ceded territory.?

For instance, the Ottawa heartland of L’Arbre Croche (Waganakising) – along Little Traverse Bay, including today’s Harbor Springs area – is shown as a reserved tract. This was the main center of the Odawa, a community of several villages that together numbered over 1,000 people. (Schoolcraft’s population table confirms the Little Traverse Odawa, combined with their kin on Beaver Island, made up more than one-quarter of all Native people in the 1836 ceded area?.

The map also highlights Beaver Island and nearby Garden Island in Lake Michigan, which had smaller Odawa bands; these islands are noted with their populations (a few dozen each) in the table and likely marked as temporary reserves where some Ottawa would remain for a few years after 1837.

Moving south and east, the map indicates other Native enclaves. Along Grand River, the Grand River Ottawas are listed – these were bands living near present-day Grand Rapids and Grand Haven. Though much of southern Michigan had been ceded in earlier treaties (Detroit in 1807, Saginaw Valley in 1819, etc.), some Chippewa groups in central Michigan still held small reserved areas. The map, for example, lists the Saginaw Chippewas and affiliated bands (the Swan Creek and Black River Chippewas) who remained in the Saginaw River region. While not heavily shaded (their lands had largely been ceded by 1819), their villages are labeled around the Saginaw and Flint area, with population figures noted (on the order of a few hundred). Likewise, the map may show a reservation at Thunder Bay (Alpena area) where a band of Chippewas resided. Schoolcraft’s color coding differentiates these older reserves: one color (perhaps a red outline) is used to mark earlier reservation tracts from older treaties, whereas yellow denotes the fresh 1836 treaty reserves – a visual key to the layered history of land cessions.

Importantly, the Potawatomi of southern Michigan appear on the map as a people in transition. By 1837, most Potawatomi had been pressured to sign removal treaties (1833–1836) and were being removed west of the Mississippi. The map labels former Potawatomi territories – the St. Joseph River valley, Kalamazoo, and Huron River areas – but notes that few Native inhabitants remain there. In the southwest, Schoolcraft makes note of Chief Leopold Pokagon’s band, the one Potawatomi group that obtained permission to stay in Michigan. Centered near Dowagiac and the St. Joseph River, Pokagon’s Catholic Potawatomi band of roughly 250 people is likely referenced in the population table. Other Potawatomi villages are shown only as historical references, with annotations like “Potawatomies mostly removed in 1837” or similar. This stark change is part of the map’s story: it captures the aftermath of Indian Removal in lower Michigan – out of an estimated 7,000–8,000 Native people in Michigan, only a few hundred Potawatomi had actually left by that point, meaning most remained despite federal efforts?.

The Lower Peninsula section also pinpoints the locations of U.S. Indian agencies and forts that managed relations with these communities. Mackinac Island, at the straits, is marked as the headquarters of the Mackinac Indian Agency, which by 1837 was the central agency for all of Michigan’s tribes?.

Schoolcraft oversaw this agency and used Mackinac as the distribution point for annual treaty payments, so the map highlights it (with an “Agency” label and perhaps an American flag icon). Fort Mackinac, perched above the agency, is implicitly present (the map shows the island and notes the fort’s vicinity). Further south, at the junction of Lake Huron and the St. Clair River, Fort Gratiot (Port Huron) is likely indicated – a U.S. fort built to guard the Michigan-Canada corridor. Detroit’s old fort (often called Fort Shelby) had fallen out of use, but the map may still mark “Detroit” with a symbol denoting the former fort or military reserve lands there.

Geographically, the map in 1837 shows Michigan’s Lower Peninsula divided among a patchwork of Indian reservations (especially in the north) and the expanding American settlements mostly in the south and east. It uses color tints and labeled symbols to distinguish Indian-held sections from counties open to American settlement. Notably, territorial and county names are in flux: the map might outline some early county boundaries (Michigan’s counties were being organized rapidly in the 1830s), but it also uses Native names for certain areas. For example, Schoolcraft, who famously named many Michigan counties after Indigenous words, had christened places like Leelanau, Tuscola, and Allegan – such names may appear on the map’s margins if county lines are sketched in?.

Where relevant, he also uses French and Native terms (e.g., “Cheboigan” for Burt Lake, “Mash-She-She” or similar for locales) that modern readers might not immediately recognize. This mix of nomenclature on the Lower Peninsula reflects a time when Michigan’s political geography was being redrawn, even as Native geographic knowledge still defined many places.

Detroit and Southeast Michigan: Old Settlements and Fading Native Presence

By 1837, Detroit had evolved from a frontier fur post into the new state’s urban hub, and the map treats it accordingly. Detroit is labeled in the southeastern corner, shown as the administrative center (it was formerly the seat of the Michigan Superintendency of Indian Affairs in territorial days). However, the Indigenous presence around Detroit had largely diminished. The map notes the former lands of the Huron (Wyandot) and Potawatomi peoples in this region: downriver from Detroit were the Wyandot of Brownstown and Monguagon, and to the northwest were Potawatomi villages along the Huron River. Schoolcraft uses annotations to indicate these groups but likely comments that they have “removed” or ceded their claims. (The Wyandot, for instance, had a reservation in Michigan, which they gave up in an 1836 agreement, preparing to relocate to Kansas a few years later.) Thus, around Detroi,t the map has more historical notes than current Native sites – a stark contrast to the heavy shading of reservations up north.

Detroit itself is depicted with symbols of American authority. The map marks the site of Fort Detroit, possibly by a small block or red dot near the “Detroit” label, although the fort’s palisades had been mostly dismantled by then. Also present is the United States Indian Office: as Michigan transitioned to statehood, the Office of Indian Affairs’ local superintendency likely continued operations in Detroit in some capacity. The Acting Superintendent (Schoolcraft) was headquartered at Mackinac, but Detroit remained an important coordination point, so the map might denote government offices there. Additionally, major transportation routes – like the Saginaw Trail and Chicago Road – emanating from Detroit could be sketched since these would soon define settler movement into former Native lands.

Some geographic names in southeast Michigan on the map reflect older usage. The River Rouge and River Raisin, for example, might be labeled, and areas like “Maumee” or “Toledo” appear near the border, reminding viewers of the recent Toledo Strip dispute (Michigan’s surrender of Toledo to Ohio in exchange for the Upper Peninsula in 1836). Indeed, the map fixes Michigan’s new boundaries: it shows Toledo in Ohio. Clearly, it labels the “Ohio” border just south of Detroit, a poignant inclusion given that only a year prior, Michigan had claimed that area. To the northeast, the map likely labels “Lake St. Clair” and the St. Clair River accurately but may use the older term “Swan Creek” Settlement for the area of today’s Chesterfield Township where some Chippewa had briefly resided.

In essence, the Detroit section of the 1837 map serves as an epilogue to Michigan’s Indigenous geography. It identifies where Native communities had been – Wyandot at “Gross Ile” and “River Huron,” Potawatomi along the St. Joseph River (far south near the Indiana line), etc. – and by omission or note shows they were no longer significant in those locales. The color coding here is sparse; southeast Michigan has no shaded reservations on the map because those treaties were decades past. What remains highlighted is Detroit’s role as a gateway city and the headquarters of U.S. authority. The map’s neat delineation of counties and territory in the Detroit region, contrasted with the multi-colored patches up north, visually tells the story of Michigan at statehood: the south and east firmly under American settlement, and the north still a mosaic of Anishinaabe homelands just then being drawn into the American fold.?

Map Legend, Color Coding, and Notable Terminology

Schoolcraft’s map includes a legend (titled “References”) using color codes and symbols to convey meaning. According to contemporary descriptions, the colored areas correspond to Indian reservations created by various treaties?.

Yellow shading is used to mark reservation tracts set aside under the 1836 Treaty of Washington, which involved the Ottawa and Chippewa ceding lands in exchange for certain areas reserved for their use?.

These yellow-tinted zones appear prominently in northwest Lower Michigan (e.g. around Little Traverse Bay) and parts of the eastern Upper Peninsula, aligning with the treaty’s designated reserves. In contrast, red or dark shading on the map is used for older reservations or special land parcels from earlier treaties. For instance, small reserve patches from the 1819 Treaty of Saginaw (for the Chippewa) or 1827 Treaty of St. Joseph (for the Potawatomi) might be outlined in a different color to distinguish them from the 1836 treaty reserves. The legend text (partially visible on the map) suggests categories based on treaty dates or size – it lists entries like “Reservations by Treaty…1836 marked [yellow]” and possibly “Reservations by Treaty…1837 marked [red],” etc., indicating the mapmaker differentiated recent agreements from past ones.

Symbols on the map further enhance its information. A square icon, often filled in red, denotes a fort or military post. We see this at Fort Brady in Sault Ste. Marie and at the site of Fort Mackinac, and one near Detroit, each likely marked by such a square. An American flag or pennant symbol is used to show U.S. Indian Agency offices. On Mackinac Island and at Sault Ste. Marie, Schoolcraft placed these symbols to locate the agency headquarters and sub-agency respectively?.

Mission stations (if any are noted, such as a mission at Mackinaw or an Ojibwe mission on Grand River) might be marked by a small cross or chapel symbol, though the map’s primary focus is administrative. Rivers, lakes, and treaty boundary lines are drawn in ink – for example, a bold line likely traces the 1836 treaty boundary across the Upper Peninsula, separating the ceded eastern portion from the unceded west.

The terminology on the map reflects the era’s language. Schoolcraft uses the term “Ottowa” and “Chippewa” for the Odawa and Ojibwe – common 19th-century spellings. He labels regions like “Michilimackinac”, an older name encompassing Mackinac Island and the Straits area (also the name of the county in 1837). This French-derived name stands out to modern eyes, as today we say “Mackinac.” Similarly, the map refers to “Lake Michigan,” “Lake Superior,” and “Lake Huron” by their current names, but may use archaic spellings for smaller features (for example, the “Menomonee” River for Menominee River). The new political units are noted: “Wisconsin Ter.” is shown bordering Michigan to the southwest and west, since Wisconsin Territory had just been formed in 1836, taking over the lands that were formerly part of Michigan Territory. The presence of that label on the map is itself a timestamp – a reminder that when Michigan was a territory, it included what became Wisconsin; by 1837, that is no longer the case, and Schoolcraft’s map duly notes Wisconsin as a separate entity.

Another notable term is in the map’s title block and notes. Schoolcraft signs it as “Acting Supt. Ind. Affrs. Michigan” and addresses it to his superiors in Washington. He dates it “Michilimackinac, Sept. 15, 1837,” using the old word for Mackinac?.

This choice of wording is significant: it harks back to the 18th-century Fort Michilimackinac (on the mainland) and shows continuity with earlier times. It’s also a nod to the fact that Mackinac Island was a meeting ground of cultures – a place known by a French name, inhabited by Anishinaabe people, and now serving as a U.S. agency site. Overall, the map’s legend and terminology combine to provide a richly coded artifact. Modern readers, with its key in hand, can translate the colors and symbols to understand 1837 Michigan’s delicate balance of power – yellow patches for Native refuges, little squares for forts, and names that blend Indigenous, French, and American influences.

Sources:

Schoolcraft, Henry Rowe. A Map of the Acting Superintendency of Michigan. Manuscript map, Michilimackinac, 1837. National Archives, Washington, D.C. Web. Accessed 3 Apr. 2025.

“The Mackinac Indian Agency: Administrative Center for Indian Affairs in the Great Lakes.” Mackinac State Historic Parks, Mackinac Parks, n.d., www.mackinacparks.com/the-mackinac-indian-agency-administrative-center-for-indian-affairs-in-the-great-lakes/. Accessed 3 Apr. 2025.

“Fort Brady.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, Wikimedia Foundation, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fort_Brady. Accessed 3 Apr. 2025.

Fletcher, Matthew L. M. “1836 Ottawa and Chippewa Treaty: Population Data and Reservation Information.” Turtle Talk, Michigan State University College of Law Indigenous Law and Policy Center, turtletalk.blog. Accessed 3 Apr. 2025.

Dunbar-Ortiz, Roxanne. An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States. Beacon Press, 2014.

Cleland, Charles E. Rites of Conquest: The History and Culture of Michigan’s Native Americans. University of Michigan Press, 1992.

Tanner, Helen Hornbeck, ed. Atlas of Great Lakes Indian History. University of Oklahoma Press, 1987.

4.5?