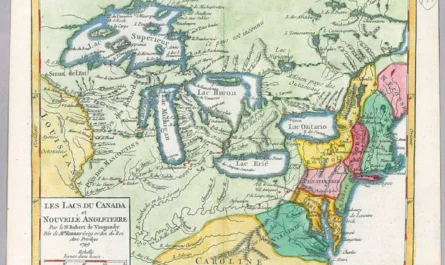

Bach, Michigan, was established in the late 19th century and named for its founder, Christian Frederick Bach. Born in 1854 to German immigrant parents in nearby Sebewaing Township, C. F. Bach was a young entrepreneur who partnered with prominent businessman John C. Liken at age 22 in 1876. He married Liken’s daughter in 1878, linking him to one of the Thumb area’s leading families. Bach set out to develop a new village east of Sebewaing, recognizing the area’s potential as rich farmland once swamplands were drained.

Video – Michigan Moments Bach Michigan History

The history of Bach Michigan, really starts with his securing a railroad stop and building key businesses; he put Bach on the map around the turn of the 20th century as a focal point for local agriculture. This small settlement – essentially a crossroads on the Sebewaing/Brookfield Township line – was significant for providing farmers a closer market and rail connection in Huron County’s interior, rather than hauling everything to distant towns. In essence, Christian Bach was the town’s namesake and driving force, and the community’s very existence is owed to his vision and influence.

Christian F. Bach’s Role and Vision

Christian F. Bach leveraged his business acumen and family ties to spur Bach’s growth. Having gained experience in Sebewaing’s lumber and cooperage industry (he and Liken ran a stave mill for barrel-making), he understood the economic transition the region was undergoing – from the waning lumber era to an agricultural future. Bach was instrumental in getting the Michigan Central Railroad routed through his new village, knowing that a rail line was the lifeblood for a rural community. He served on the boards of local banks and the Michigan Sugar Company, indicating his deep involvement in the area’s commerce.

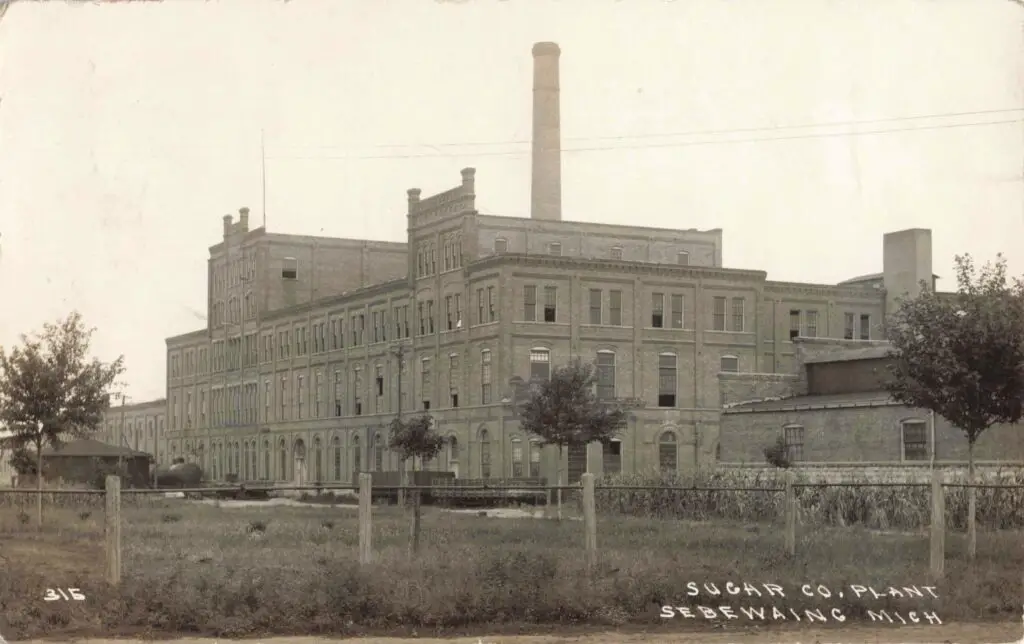

Bach helped advocate for a beet sugar factory in Sebewaing and invested in it, as sugar beet farming was emerging as a significant industry in the early 1900s. His efforts also extended to land development – he was a key supporter of draining the vast Columbia Swamp to open up new farmland.

This drainage project turned once-wild marsh into arable fields, enabling more settlers to farm (and patronize Bach’s businesses). By the early 1900s, C. F. Bach had effectively turned the village of Bach into an economic hub for the surrounding farm country. The town even bore his name as a testament to his leadership. When he died in 1920, Bach had laid a foundation that briefly made this tiny hamlet thrive beyond what its size would suggest.

Bach in the Early 1900s: A Farming and Railroad Hub

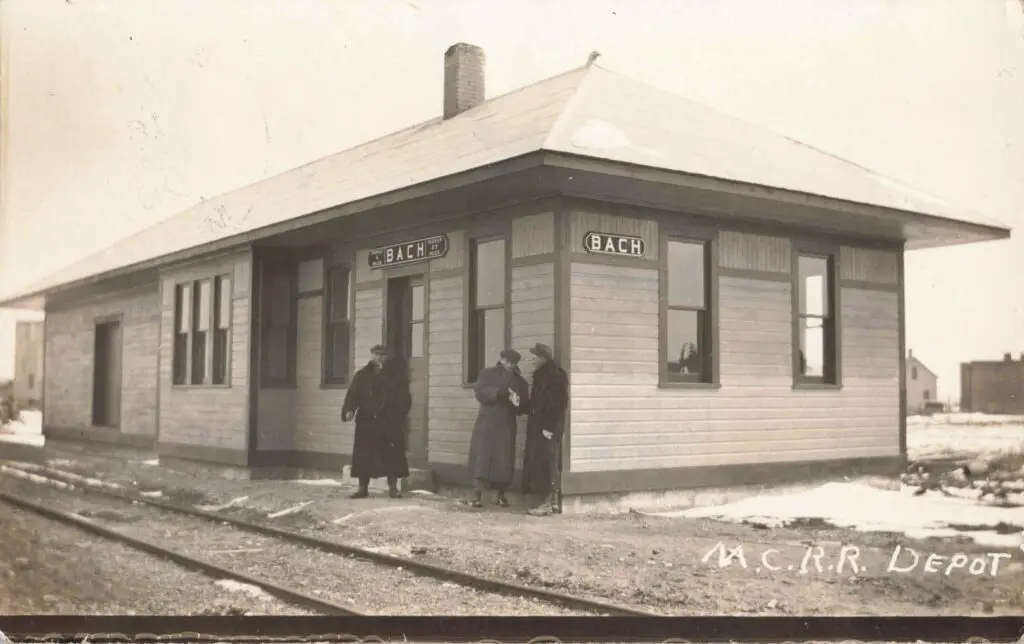

At the dawn of the 20th century, Bach, Michigan, buzzed with activity as a classic farm-town “hub” on the prairie. The Michigan Central Railroad (M.C.R.R.) depot at Bach (shown above, circa 1902) became a vital link to the outside world. Steam trains would stop at this small station – reportedly a mere flag stop on the line – to load agricultural goods and livestock bound for market. Farmers from miles around brought wagonloads of grain and herds of cattle to Bach’s stockyards and siding for shipment to larger cities.

The railroad not only carried out the Thumb’s bounty of sugar beets, navy beans, and dairy products, but also ferried in necessities for rural life. Bach’s importance grew as a local market center: at its height in the early 1900s, the village boasted a two-story hotel, two saloons, a bank, four retail shops, a grain elevator, and a livery stable for horses. Such amenities made Bach an oasis of commerce in a landscape of family farms.

The St. Peter’s Lutheran Church in Bach anchored the community’s social life, serving a predominantly German-American populace and holding services in German well into the 1920s. The first English service didn’t occur until 1930, reflecting the strong German heritage. Life in Bach revolved around the rhythms of the seasons and the railroad timetable – during harvest, the depot was a busy scene of farm wagons, while in winter the pace slowed. For a brief period, this little village thrived as a minor agricultural hub where rail, road, and rural society intersected.

The Central Role of the General Store

One of Bach’s focal points was its general store, which doubled as the post office and carried an astonishing variety of goods for early 20th-century country life. Pictured in 1918, the Bach General Store and Post Office was a single-story clapboard building adorned with numerous signs. Advertisements for Studebaker wagons and buggies and the Johnston Harvester Co. farm machinery adorned the storefront, signaling that one could buy everything from a pair of boots to a new hay mower here.

The store’s proprietor also acted as postmaster, handling mail for residents once a post office was established in the community. Locals would stop in not just to trade butter and eggs for staples, but to pick up mail, share news, and even arrange rail freight. In front of the store, implements and barrels were often displayed, and a large Pepsi-Cola logo (added in later years) promised cool refreshment.

This humble building was the heart of Bach – a place where farmers, traveling salesmen, and townsfolk mingled. Its presence, along with the depot, gave Bach an outsized importance on the rural map. As one account noted, by 1900 Bach had become an “economic hub” for the farming area east of Sebewaing.

For a town that was essentially just a few blocks of buildings, Bach offered just about everything a turn-of-the-century farm family might need: a blacksmith and livery to service their horses, a grain elevator and stock pens to handle their harvests and livestock, a hotel and saloons for travelers or a hard-earned drink on Saturday, and the general store for all manner of supplies. In these years, Bach was truly a bustling little whistle-stop of prosperity amid the wheat fields.

Owendale – Rails and Agriculture in a Neighboring Village

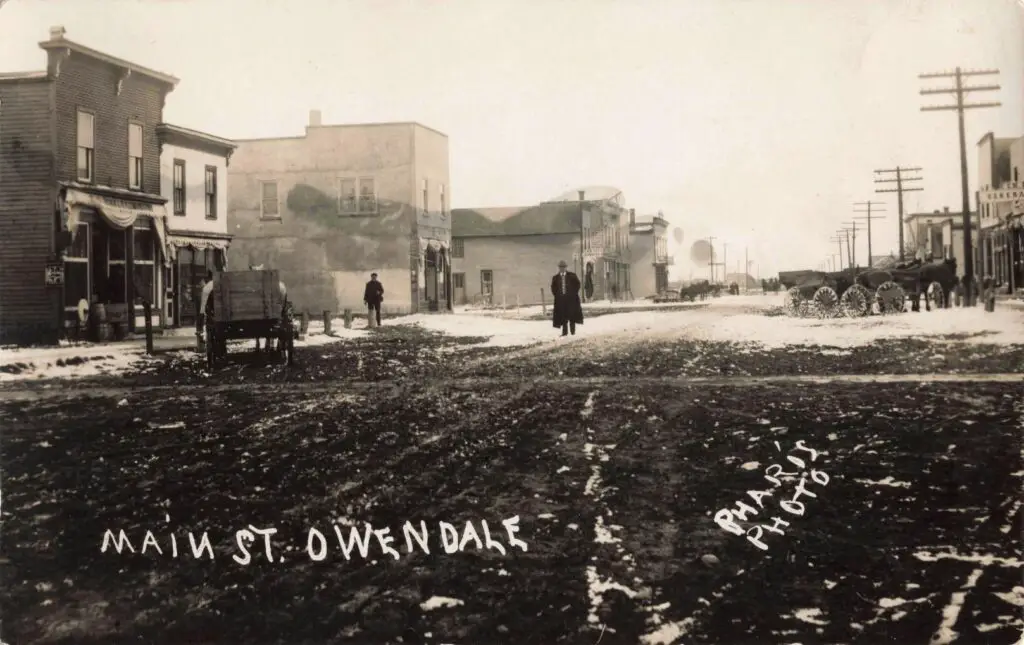

Not far from Bach, the village of Owendale was following a somewhat parallel trajectory – though its roots were in the lumber boom. Owendale was founded by two cousins from Saginaw, John G. and John S. Owen, who in 1882 purchased a tract of timberland in the Columbia Swamp region of Huron County. They established a sawmill by 1883 to harvest the area’s oak forests, and a small settlement grew up around this mill. John G. Owen even hired a surveyor in 1887 to plat a town site, formally naming it Owendale after the family name.

In its early years, Owendale was primarily a logging camp that evolved into a village – until the timber supply was exhausted. The great sawmill burned down in 1896, marking the end of the lumber era and forcing the community to shift its focus to agriculture. Conveniently, the timing coincided with the arrival of the railroads. By 1900, multiple rail lines had reached Owendale, transforming it into an essential local junction.

The Pontiac, Oxford & Northern (later part of the GTW, Grand Trunk Western) built a branch line toward nearby Caseville, and the Michigan Central built its Caro-Owendale branch coming in from the south. In fact, in 1902, a new union depot was constructed in Owendale to serve both railroads – a clear sign of the village’s rising fortunes. This dual railroad service made Owendale a key shipping point for wheat, beans, sugar beets, and other farm products in the Thumb.

The agricultural boom of the early 20th century brought new faces as well: in May 1901, a group of Volga German families (German-Russian immigrants) arrived from Nebraska to work in the sugar beet fields around Owendale. They were drawn by the burgeoning Michigan Sugar Company operations (Sebewaing’s beet sugar factory had opened in 1902) and helped boost farming in the area. With rail connectivity and fertile, drained land, Owendale grew into a small but thriving village; it was officially incorporated in 1905.

In the early 1900s, Owendale featured its downtown area with hardware and general stores, a depot agent coordinating freight trains, and grain elevators to store the local harvest. Though never a large town (population only a few hundred), Owendale was bustling enough that one lifelong resident recalled it as a “large, bustling community” in those days. The tale of Owendale underscores how the railroad and sugar beet economy invigorated many Thumb communities at the turn of the century.

Kilmanagh – A Four Corners Community Frozen in Time

In contrast to Bach and Owendale, the tiny hamlet of Kilmanagh never quite rode the same wave of sustained growth – yet its story in the early 1900s is equally fascinating. Kilmanagh began as a classic “four corners” settlement, where two country roads crossed at the juncture of four townships. The first settler, an Irish immigrant named Francis Thompson, arrived in 1861 and established a farm and wayside tavern at what was then called Thompson’s Corners. He later gave the place a more sentimental name – Kilmanagh – after a locale in his Irish homeland.

Kilmanagh’s development took off after the Civil War when homesteaders poured into Huron County. Crucially, a state road was built in the late 1860s linking the Saginaw Bay port of Sebewaing to Harbor Beach on Lake Huron, and this road ran right through Kilmanagh’s crossroads. Thus, Kilmanagh became a convenient stop for travelers and a service center for surrounding farms, even without any railroad. By the 1870s and 1880s, this small village had a post office (opened in 1873) and was emerging as a thriving community.

The noted Sebewaing entrepreneur John C. Liken – the same man who mentored C. F. Bach – built Kilmanagh’s first general store in 1873 to supply a nearby sawmill he owned. That store, a two-story wooden structure with boarding rooms upstairs for lumberjacks, quickly became Kilmanagh’s centerpiece. Through the late 19th century, Kilmanagh prospered modestly as the surrounding pine woods were cleared and turned into farms. By 1891, it was a lively rural hamlet featuring two general stores, a grist mill, a blacksmith shop, and a couple of saloons – enough business that the dusty intersection earned a reputation as a little “downtown” of its own.

Unlike Bach or Owendale, Kilmanagh never had a railroad to propel it further; it remained dependent on horse-and-wagon traffic. And that limitation began to tell in the 20th century. “Kilmanagh never attracted a railroad line,” notes one county history, which observed the village stayed small because it was “several miles from any railroad”. Indeed, when rural free delivery expanded, Kilmanagh’s post office was discontinued in 1904 (local mail shifted to Sebewaing), a sign that the community’s peak had passed.

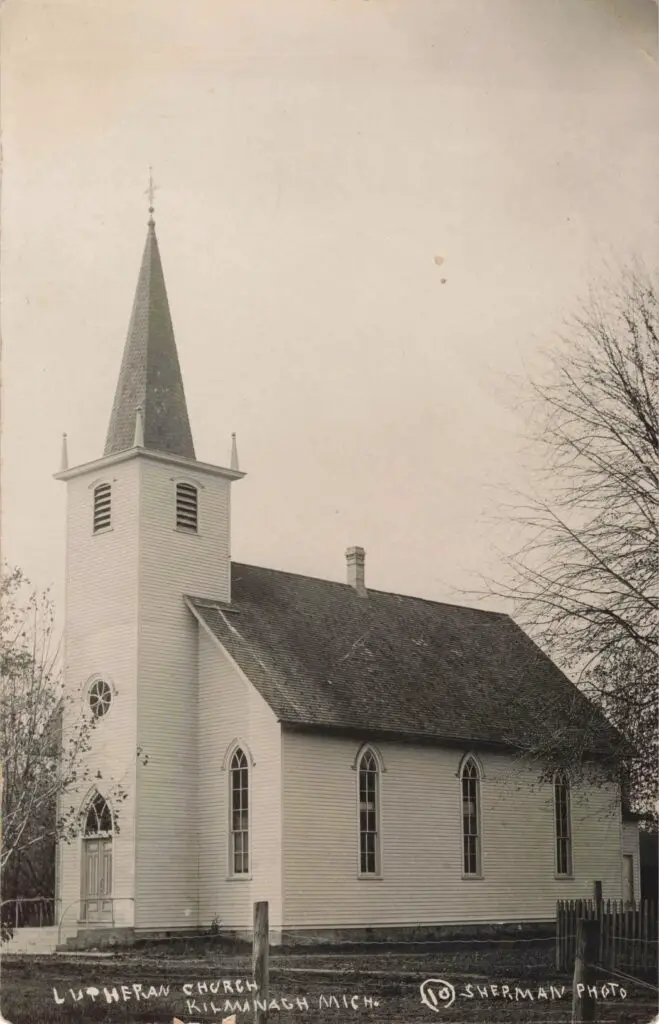

Still, in the early 1900s Kilmanagh hung on as a close-knit farm community – its old Lutheran church (St. John’s, founded in the 1870s by German settlers) continued to hold services, and the general store remained open, serving coffee and supplies to locals who gathered around its potbelly stove. The absence of railroads meant Kilmanagh changed more slowly than its rail-connected neighbors; it truly was a time capsule of the late 1800s. Even today, the weathered Rummel & Woldt General Store still stands in Kilmanagh, a rare survivor of that era, now undergoing loving restoration rather than bustling with customers.

Sebewaing – The Mother Community’s Influence

Towering in the background of all these small towns is Sebewaing, the nearest sizable town and an industrial hub of Michigan’s “Upper Thumb.” Sebewaing (named from an Ojibwe word meaning “crooked creek”) was founded much earlier, in 1845, originally as a Lutheran mission and fishing village on Saginaw Bay. By the late 1800s, under the leadership of figures like John C. Liken, Sebewaing had blossomed into the economic powerhouse of Huron County’s southwest corner.

It was incorporated as a village in 1879, and its harbor bustled with schooners shipping out farm produce, fish, and lumber. In one year (1879), Sebewaing’s docks exported 135,000 bushels of grain, 50,000 pounds of butter, 4 million wood staves, and millions more shingles, barrel hoops and board-feet of lumber– an example of how much commerce flowed through that town.

This prosperity paved the way for the region’s biggest venture: a beet sugar factory. In September 1901, ground was broken in Sebewaing for a large sugar beet processing factory, and by the fall of 1902, the plant began its first “campaign,” slicing local beets into sugar. C. F. Bach and his father-in-law, Liken, were key players in making this factory a reality. The Sebewaing sugar factory (later part of Michigan Sugar Company after 1906) became a major employer and guaranteed a steady market for farmers growing beets. This, in turn, affected Bach and Owendale – farmers there could send their beets to Sebewaing by rail, and many local people found seasonal work “at the sugar end” in town.

Sebewaing’s influence was also direct: Liken’s company ran a network of general stores (as noted, one in Kilmanagh) and other enterprises across the Thumb. Sebewaing itself around 1900 was a thriving community with electric lights, breweries (Sebewaing had its brewery since 1880), banks, and all manner of shops. It was the kind of “big town” where residents of Bach, Owendale, and Kilmanagh would go for specialized business – whether it be to attend high school, visit a hospital, or, in earlier years, to catch a lake steamer.

In short, Sebewaing was the economic anchor of the area, and the smaller villages grew or waned in its orbit. Bach, for example, was essentially an offshoot of Sebewaing’s expansion, founded by a native of Sebewaing and connected through the sugar industry and railroad. Understanding Sebewaing’s boom helps explain why these little communities even existed: they were supporting players in a landscape dominated by farming, which Sebewaing’s industries (from barrel factories to sugar refining) made profitable.

Decline and Legacy of Bach and its Neighbors

By the mid-20th century, the bustling scenes in Bach and its sister villages had largely faded. Several forces led to their decline or arrested development. In Bach’s case, the Great Depression of the 1930s dealt a devastating blow – local crop prices collapsed, businesses folded, and Bach’s only bank went under. Many of the establishments that had made Bach lively were gone by World War II.

The Michigan Central Railroad, which had been Bach’s raison d’être, eventually abandoned its branch line; today a faint diagonal trace across the landscape is all that remains of the tracks. With the railroad closed and no highway running through town, Bach slowly drifted into obscurity as a quiet crossroads. Its general store limped along for years (in later decades functioning as an antique shop), but ultimately even that closed, leaving the building as a sort of informal museum of old relics behind dusty windows.

Nearby Kilmanagh’s decline set in even earlier – without a rail connection, it never grew past the horse-and-buggy era. After its post office shut in 1904, Kilmanagh became a “ghost town” in slow motion, gradually losing businesses until the landmark Rummel’s general store finally closed in 1963 after nearly 90 years in operation. Owendale, which had once enjoyed two rail lines, saw those fade away as well: the Michigan Central cut back its line to terminate at Bach, and the Grand Trunk Western’s service eventually ended as rail traffic dwindled mid-century.

Owendale’s population shrank, but it survived as an incorporated village and farming community – smaller and quieter than its heyday, yet still on the map. Meanwhile, Sebewaing weathered the 20th century better thanks to its larger size and industrial base (the sugar factory kept running for many decades, and Sebewaing diversified into other businesses and even an airport).

Examining why Bach remains a small, lesser-known place today reveals a common theme: transportation and economics have bypassed it. When the age of automobiles and paved highways came, Bach had neither a major road nor sufficient size to attract development. Residents began driving to bigger towns (like Pigeon or Bad Axe) for shopping, undercutting the need for local stores. Younger generations left for cities, and the surrounding family farms consolidated into larger operations with fewer people.

By around 1960, Bach and Kilmanagh were essentially relics of a bygone era – their roles as rural trade centers no longer needed. And yet, there is a bittersweet legacy in these quiet places. The old buildings, such as the Bach General Store with its peeling Pepsi logo and the Kilmanagh General Store with its false-front façade, still stand as tangible reminders of the early 1900s, when these towns thrived.

In a historical documentary narrative, Bach, Michigan, and its neighboring communities tell a classic American tale: a boom-and-bust cycle of a rural region. From humble founding by determined individuals (be it a German cooper’s son like C. F. Bach, or the Owen cousins, or an Irish crossroads tavern-keeper), to the prosperity brought by rails and agriculture, to the gradual ebbing when the economic tides shifted – their story is the story of countless small towns.

Today, Bach is little more than a “quaint stop” with a few homes and a church on a country road, but its early 20th-century spirit lives on in the lore and landmark remnants that creative locals and historians are striving to preserve. Each empty lot or weathered depot foundation in Bach, Owendale, or Kilmanagh whispers of a time when the Thumb of Michigan was newly settled, railroads were king, and even the smallest village could dream of growing into something grand. It’s a legacy that, while quiet, richly informs the region’s heritage.

Sources for the History of Bach Michigan

- Atlas of Huron County, Michigan. Philadelphia: F.W. Beers & Co., 1875. Print.

- Bach, Christian Frederick. “Biographical Sketch.” History of Huron County, Michigan. Chicago: H.R. Page & Co., 1884. pp. 243–244.

- “Bach General Store and Post Office (RPPC Image c.1918).” Private Collection, Thumbwind Publications Archives.

- Gansser, Augustus H. History of Bay County, Michigan and Representative Citizens. Chicago: Biographical Publishing Co., 1905.

- “History of Sebewaing, Michigan.” Sebewaing Area Historical Society, www.sebewainghistory.org. Accessed July 2025.

- “Kilmanagh General Store Restoration Project.” Friends of Kilmanagh. https://kilmanagh.org. Accessed July 2025.

- Michigan Central Railroad Timetables, 1902. University of Michigan Transportation Library Archives.

- “Owendale Centennial History Book: 1905–2005.” Owendale Historical Society, 2005.

- Plat Book of Huron County, Michigan. Rockford Map Publishers, 1916.

- “St. Peter’s Lutheran Church Records.” Evangelical Lutheran Church in America Archives, Huron County Synod Section.

- U.S. Federal Census Records for Sebewaing and Brookfield Townships, Huron County, Michigan (1900–1940). National Archives and Records Administration.

- Weeks, George. Michigan: A History of the Great Lakes State. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1987.