The summer of 1911 in Michigan was hot and dry. However, temperatures in Iosco County during the first week of July 1911 were between 90 and 100 degrees in the shade. The devastation of the 1911 Oscoda and AuSable fire that wiped out these two eastern Michigan towns would be compared to the Great Peshtigo Fire in 1871 due to its destruction of both of the shoreline lumbering towns.

What We Will Cover

Video – July 1911 Fires in AuSable and Oscoda Michigan – Michigan’s Forgotten Inferno

The Town of AuSable in 1911

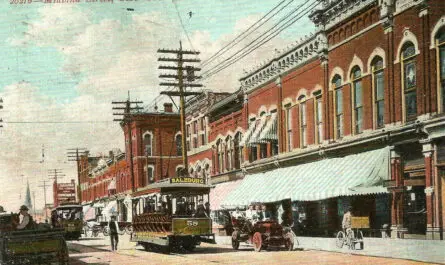

Oscoda and Au Sable were thriving twin towns straddling the mouth of the Au Sable River on Lake Huron’s shore. In the late 1800s, they rose to prominence during Michigan’s lumber boom. Au Sable was once the larger of the two, with a peak population claimed near 10,000 at its height. By the 1870s–1890s, both communities were bustling ports and mill towns – though by 1911 their glory days were waning. Au Sable boasted six sawmills, a sash and door factory, three hotels, three churches, several general stores, and even a bank.

The H.M. Loud & Sons Lumber Company ran a massive sawmill complex in Au Sable, and the Au Sable River Boom Company corralled logs floating downriver to feed the mills. Oscoda, on the north bank, was slightly smaller (its population fell from about 3,500 in 1890 to under 900 by 1910 as local timber was depleted. Still, Oscoda had its own mills and businesses, and together the twin towns were a major lumber shipping hub in northeastern Michigan.

By 1911, the lumber era was nearly played out and population had declined – “formerly of ten thousand, now about two thousand,” as one visitor observed. Many remaining residents were directly tied to the timber trade or related enterprises. Every structure in both towns was wooden – houses, hotels, saloons, sidewalks – all built from the rich pine forests that once surrounded them.

Streets were literally covered in wood chips and sawdust (used for traction and mud control), and huge stacks of cut lumber filled yards along the river. This setting made the towns prosperous in the lumber boom, but it also meant a tinderbox waiting for a spark. In fact, a visiting clergyman in 1908 remarked that Oscoda and Au Sable were “built of kindling wood on heaps of sawdust”, warning that if a fire ever caught hold, “it would be burned up in five minutes, like Metz” (a nearby town that had burned in 1908). That grim prediction proved prophetic three years later.

A Perfect Storm of Fire Conditions

Several environmental and human factors set the stage for the disaster. The summer of 1911 was exceptionally hot and dry. During the first week of July, temperatures in Iosco County hovered between 90° and 100°F in the shade. A local newspaper quipped with dark humor that it was so hot, a man knocking at the gates of Hell pleaded for a “cool spot,” to which the devil replied, “Come in quickly and close the door”,

More tangibly, the Tawas Herald reported on July 7, 1911 that “Saturday, Sunday and part of Monday were among the warmest days known here in a long time, the mercury ranging from 94 to 100 in the shade.” The heat had followed a period of scant rainfall, leaving the pine slashings and brush in the area bone-dry.

In these conditions, brush fires were breaking out all over northern Michigan. Small forest and brush fires smoldered in at least 21 counties that week. In the plains around Oscoda and Au Sable, residents commonly used slash-and-burn techniques to clear land. Local lore even suggested that some fires were intentionally set in the spring to burn off underbrush and encourage huckleberry growth for the next year. By July 10–11, smoke was already in the air around the Au Sable River.

One forest fire had been hovering just outside Au Sable for three days prior to the catastrophe, burning near a new chemical plant west of town. The townspeople, however, were not overly alarmed – they continued business as usual, “confident that their city would not be burned” They had seen fires in the distance before, and most assumed this one would skirt past the town.

Unfortunately, the region was primed for disaster. The sheer quantity of combustible material in the towns was immense – rows of wooden buildings, stacks of dry lumber, sawdust-lined roads, and even the very ground enriched by years of wood debris. The drought and a stiff wind would turn any spark into a conflagration. That spark (in fact, multiple sparks) came on July 11, 1911. High winds from the northwest began to howl at up to 50 miles per hour, fanning the smoldering countryside fires into open flames. Even worse, around mid-day, a passing locomotive on the Detroit & Mackinac Railroad just west of Oscoda emitted sparks from its smokestack.

The hot cinders landed in the dry grass and brush along the tracks about a mile outside of town – immediately igniting a fire in the brittle weeds. This would prove the fatal spark that Oscoda’s fate hung on. The blaze from the railroad right-of-way raced toward Oscoda, feeding on pine slash. To compound matters, at the Au Sable & Northwestern Railway’s freight office in Au Sable, a large keg of gasoline exploded when touched by advancing flames, sending fire in every direction. What had been local brush fires suddenly turned into an unstoppable firestorm aimed straight at the heart of the twin towns.

Just Another Day in Oscoda and AuSable

Tuesday was simply another day for the residents of these twin towns that straddled the AuSable River. The Mill was up and running, businesses were open, and ladies were going about their daily lives. Children escaped the heat by playing on the beach. Everyone was oblivious to the smokey odor of flames raging outside the settlements.

Timeline of the Disaster – July 11, 1911

Morning, July 11: By late morning, residents of Au Sable grew uneasy as gusty winds drove the nearby forest fire toward the town’s edge. Small blazes actually reached the western outskirts of Au Sable earlier in the day – two houses in West Au Sable caught fire and burned before noon. The local bucket brigade and citizens likely managed to douse those, giving a false hope that the worst was over. Once those flames were quenched, “Au Sable seemed safe from the devastation underway in Oscoda” across the river, an observer recalled. Indeed, Oscoda at that moment had yet to face the onslaught.

Around 2:00 p.m., however, conditions took a sharp turn for the worse. The wind, now howling, injected fresh life into every spark. What started as a few brush fires became a unified front of flames. The fire west of Oscoda (sparked by the train) had been creeping closer, and embers began to rain on the town. At roughly 3:30–4:00 p.m., a “great wall of flame” bore down on Oscoda from the west. Witnesses described it as moving with incredible speed.

At the Barlow farm just outside Oscoda, flames leapt from the brush and roared toward town along the Au Sable & Northwestern railroad tracks. Within moments the fire reached Oscoda’s structures – “Within five minutes, twenty houses were ablaze on Main Street”. The blaze spread from building to building with explosive speed, igniting stores, hotels, and homes. Facing a sudden inferno, the residents had no time to save any belongings – the only choice was to run for their lives.

As Oscoda’s downtown went up in flames around 4 p.m., people fled in all directions. Many ran east toward the shores of Lake Huron, pursued by what one account called a “stampede of fire” behind them. Others raced to the docks on the Au Sable River. It so happened that the steamer Niko – a lumber freighter from the Edward Hines fleet – had just arrived at Oscoda’s south dock that afternoon. The Niko was there to load lumber, but it became a lifeboat for the town. Men ran up and down the streets, shouting for women and children to head to the Niko.

Panicked crowds converged at the waterfront, eyes stinging from smoke, as embers and burning debris rained from the sky. By this time, Oscoda’s entire business district was engulfed. One resident later said the flames were “leaping 100 feet high and roaring like a furnace” as they closed in.

At the river docks, a desperate evacuation unfolded. About 280 people – mostly women and children – clambered aboard the Niko. The scene was chaos: the sky turned dark with smoke, and small fires even ignited on the Niko’s decks and cabins from flying embers. As the captain, Capt. Frederick Meyer, prepared to cast off, some men already on board yelled to “pull out” immediately – but local volunteers like Eli Herrick and Peter McPhail physically stood by the lines and refused to let the crew cast off until every last person possible was aboard. Their bravery bought precious minutes for more refugees to pile on.

Finally, the Niko backed away from the dock with its superstructure on fire in places. Once safely out in the river, the crew and passengers managed to extinguish the burning embers on the ship. The Niko could not land at nearby East Tawas due to heavy seas (the wind had whipped the lake into a froth), so the steamer steamed over 70 miles south to Bay City to unload the Oscoda survivors. (Contemporary reports varied – one report said the Niko took some refugees as far south as Port Huron, but most accounts indicate Bay City as the destination after failing to dock at Tawas).

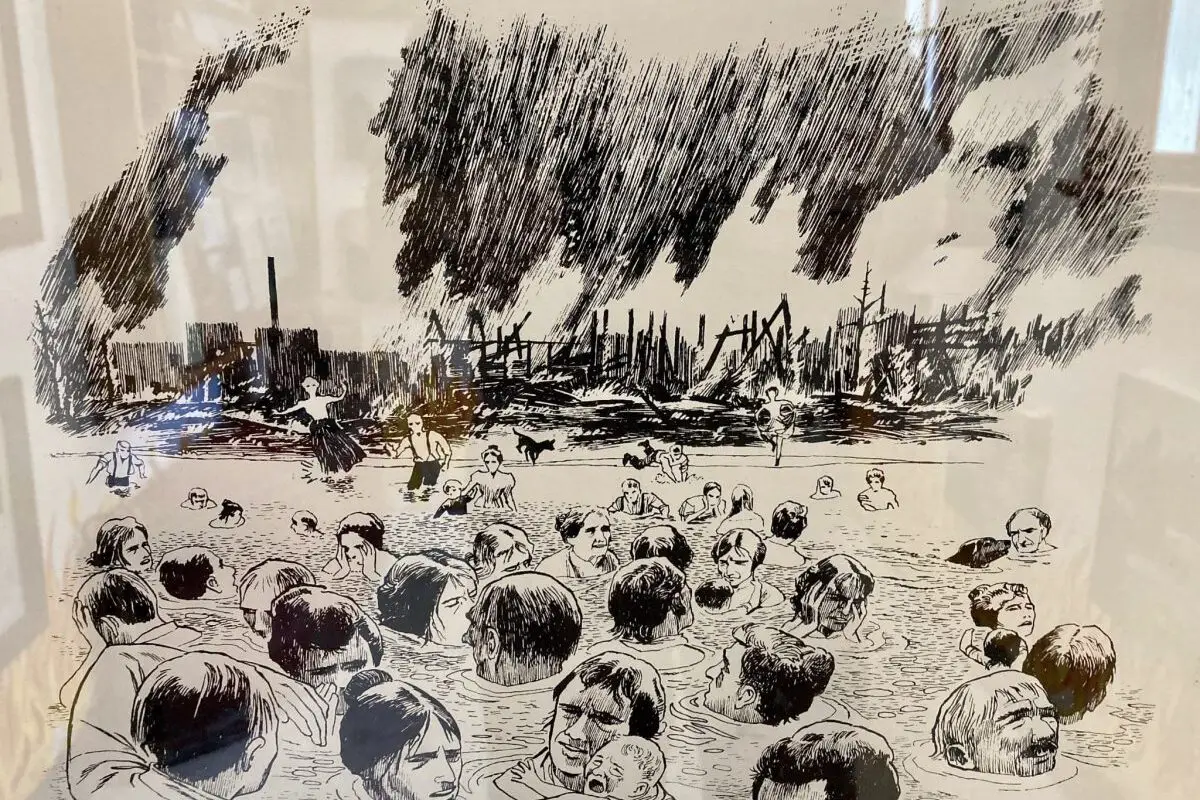

Meanwhile, others escaped Oscoda via rail. A southbound Detroit & Mackinac passenger train heroically ventured into the burning town to take on refugees. As it departed, passengers had to shut windows against blistering heat; the train raced through flame-lined tracks as it left Oscoda. Still more residents had no option but to flee into the waters of Lake Huron itself. Families waded out from the beach until the water was neck-deep – the only refuge from the searing heat on shore. Entire families stood in the lake for hours, dunking themselves and their children to avoid burns, while watching their town burn to the ground.

By early evening (5–6 p.m.), Oscoda was essentially destroyed. In the space of roughly two hours, the fire had obliterated three-quarters of the town. What had been a thriving little city that morning was now a smoking, ash-covered ruin. Only a handful of structures on the fringes remained standing. As one chronicle grimly noted, “within a scant two hours, just 20 houses were left standing in Oscoda”.

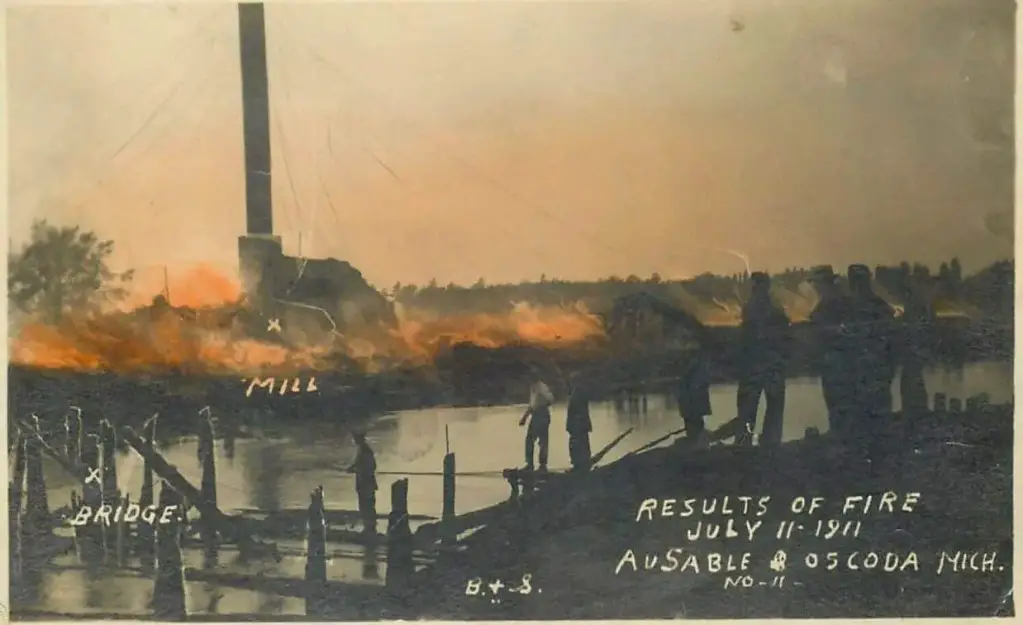

Across the river, Au Sable residents initially thought they had been spared. The wind-driven blaze that hit Oscoda did jump the Au Sable River at some points, igniting docks and even setting the bridge between the towns on fire, but in those late afternoon hours the worst of the fire seemed concentrated north of the river. Some Au Sable locals had even helped fight the earlier blaze on their west side and believed the danger was over once Oscoda started burning. But this lull did not last.

Around 7:00 p.m., the wind suddenly changed direction. What had been a northwest wind became a north or northeast wind, pushing the inferno directly into Au Sable from Oscoda’s direction. A witness described the fire’s second onslaught on Au Sable: “Turning like a horse at the starting line, the flames set a terrific pace from the north to the south limits [of Au Sable], the buildings sloughing before them as babbitt metal melts in a heated crucible”. In other words, the entire length of Au Sable city—from its northern edge by the river to its southern outskirts—was consumed in a single, swift sweep of fire.

Now Au Sable’s populace joined the panicked flight. With fire attacking from the north, hundreds of people ran southward and eastward, many ending up on the sandy lakefront beaches south of town. There, in the open dunes by the shore, rich and poor huddled together in shock through the night, “void of dignity… in mutual discomfort” under a cold north wind. Others, like those in Oscoda, plunged into the lake or the Au Sable River to save themselves.

By nightfall on July 11, both Oscoda and Au Sable had been utterly devastated. What once were orderly streets of homes and businesses were now unrecognizable fields of glowing embers. Later, survivors recounted that as dawn broke on July 12, “no one alive near the scene of the calamity [could think] but that hundreds of their neighbors had met a fearful death”. The speed and totality of the destruction made it seem impossible anyone could have survived – though thankfully, those fears were overestimated, as we’ll see below.

Cause of the 1911 Oscoda and AuSable Fire

Brush fires raged over the plains that surrounded the twin villages of Oscoda and Au Sable. The common method of clearing land in the late 1800s was slash and burn. Local lore states that one source of the fire was set intentionally to remove bush and encourage the growth of the tiny but tasty huckleberry for harvest the following year. Another source said sparks from a passing train caused yet another fire. This second fire was blamed for burning out the H. M. Loud Sons’ Lumberyard and sawmill.

By 2:00 p.m., gusting gusts of at least 50 mph had whipped the simmering fires into furious flames. The fire started slowly at first, and the soldiers battled it off. Then, however, the fire quickly spread to the first wooden structures and sawdust streets. The guys hurried back to their houses, gathering what they could and fleeing to safety with their families. Most of Oscoda and Au Sable had been destroyed in a few hours. Hundreds of individuals lost their houses and goods as they fled at the drop of a hat. Five men were killed.

One Recalls the Oscoda and AuSable Fire Up Close and Personal

One recollection of the event from Jennie Kulberg, “We reached the safety of the lake and found a crowd of people already there. Not only people but dogs, chickens, and all sorts of animals – even cats were in the water.”

“Shortly after we entered the lake, we were joined by other family members. They all had left home as quickly as possible, leaving everything behind. The fire followed so closely that a handkerchief in Father’s back pocket was ignited. Day took Henry into his arms, and Mother took Ruth, for we needed to go further into the lake. So intense was the heat that we repeatedly had to splash water onto our heads. Though I was standing on a sandbar, I remember that the water was up to my neck. Closer to shore, the heat was unbearable.”

The steamer lumber barge Niko took 280 residents to Harbor Beach, where the townspeople took them in. It was said that the captain of the Niko loaded as many people as possible from the doomed dock. Some of the ship was on fire as it finally pulled away from the dock.

After the fires, most of the town residents were homeless. Most ended up at East Tawas and Bay City.

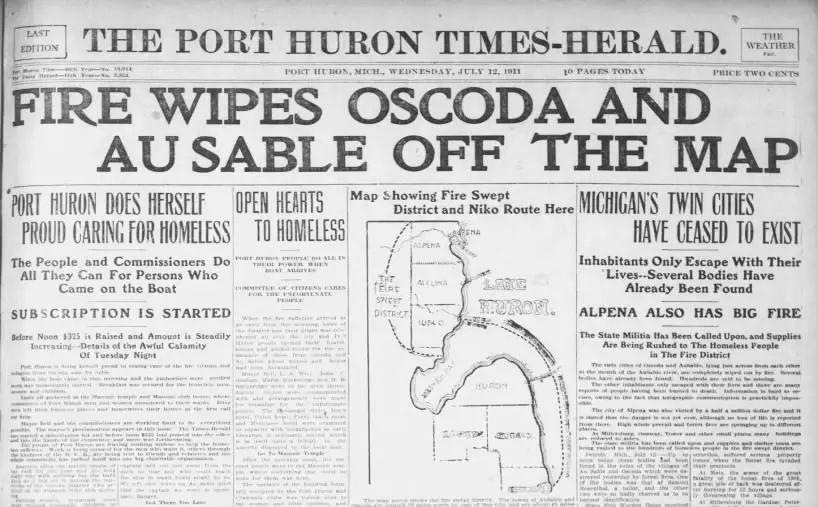

News of the Fires Swept the Nation

The Washington Times,” Hundreds Killed by Forest Fires in Michigan Towns. Ausable and Oscoda Completely Wiped Off The Map” Page one July 12, 1911

“The towns of Ausable and Oscola, Mich., lying directly across from each other on the Ausable River in northeastern Michigan were wiped off the map, and probably hundreds were killed last night by one of the worst forest fires that have ever visited Michigan.

Not a business place is standing in Oscoda today. A fierce gale fanned the fire and, within a few hours, had destroyed the little town. Sparks and burning brands swept AuSable, where the fire raged all night.

Hundreds of persons driven from their “homes by the fire took refuge on board the freighter Kongo lying oft Ausable. Others boarded the regular southbound passenger train on the Detroit and Mackinac, making its way to the stricken towns through numerous spur tracks.

The fire swept over the doomed cities with such rapidity that all the Inhabitants could do was flee for their lives, leaving behind all their belongings. The fierce rush of flames drove hundreds Into Lake Huron, and while it Is Impossible to ascertain whether any lives were lost, it Is feared that many have perished.

According to the stories of the refugees who arrived here this morning, when the train left Oscoda, the flames were leaping 100 feet high and roaring like a furnace. The heat was so Intense that those in the coaches had to close the doors and windows. Bodies are lying in Ausable’s streets, and the churches and halls are packed with those who were overtaken by the flames. Many who sought refuge from the fire were suffocated with the dense smoke. Babies carried to the water in trunks were either drowned or smothered to death.

From Alpana. and Boyne City, reports of fierce fires were received today. At Boyne City, the fires are reported to have surrounded Several logging camps and hemmed in the loggers

with a solid wall of flame. At both Alpena and Boyne City, heavy clouds of smoke could be seen on all sides.”

The Washington Times, Three Thousand Left Homeless by Fires in Michigan Woods – Scores of Persons Missing, and It Is Feared They Have Perished. July 18, 1911.

GRAYLING, Mich. July 12. Several hundred more people are homeless today due to the complete wiping out of the village of Waters, eighteen miles from here, last night. This brings the total homeless in the burning of three towns—Oscoda, Ausable, and Waters, up to 3,000.

The whole northeastern section of Michigan today Is a desolate blackened mess with only here and there a house left to mark what was only a few days ago a prosperous village or farm. Of the pile of rough pine boxes sent to Ausable and Oscoda last night for those supposed to have perished, only three have been used, but scores of Inhabitants are still missing, and no accurate estimate of fatalities can be made for some time. Only two houses In Oscoda and none In Ausable remain.

It was stated today from numerous points where fires were raging fiercely yesterday that the fire situation was distinctly Improved in northern Michigan.

According to State Fire Warden Oates, fires are reported In twenty-one counties today, and while a number of these are not dangerous at present. However, it will only take a high wind to fan them into one of the worst conflagrations the State has ever known.

The Aftermath and Impact of the 1911 Oscoda and AuSable Fires

The burned-out twin settlements quickly became a tourist attraction for people traveling by rail to the destruction at the Au Sable River’s mouth. Hundreds of tourists were alleged to have gathered to dig through the ruins of burned-out homes, searching for blobs of glass and other souvenirs.

Postcards picturing the massive mountains of scrap iron leftover from burned-out mills were quickly published. Au Sable was virtually deserted for years, and the city administration was eventually forced to revert to township status.

The 1911 fire took place two years after another large fire hit northeastern Michigan near the town of Metz. The disaster piqued public interest in controlling forest fires.

Today little evidence remains of the great fire. Instead, Oscoda and AuSable are prosperous charming lakeside towns popular with retirees and summer tourists. It is home to one of the most popular scenic drives in Michigan – Au Sable River Road Scenic Byway

Sources For the 1911 Oscoda and AuSable Fire

- AuSable-Oscoda Historical Society Iosco County Michigan via usgwarchives.net

- Major Post-Logging Fires in Michigan: the 1900’s – Michigan State University

- Huron-Manistee National Forests Lumberman’s Monument Visitor Center

- Michigan State University, Geography of Michigan – Major Post-Logging Fires in the 1900s.

- The Detroit News (via RootsWeb), July 13, 1911 report on Au Sable/Oscoda fire

- Swedish Finn Historical Society – The 1911 Oscoda, Michigan Fire (June Pelo, 2022).

- Thumbwind (Michigan local history blog), “A Day in Hell – The 1911 Oscoda and AuSable Fire,” May 24, 2025.

- Perry F. Powers, History of Northern Michigan (1912) – Chapter on Iosco County and the fire.

- Contemporary newspaper excerpts (Washington Times, July 12 & 18, 1911).

- Iosco County Historical Museum archives and Iosco County Gazette reports (1911) via USGenWeb archives.

- Personal recollections of survivors (Jennie Kulberg account via Thumbwind; June Pelo family note).

- Bentley Historical Library Image Bank, University of Michigan – postcards and photographs of the fire’s aftermath.

Until I received this email, I never knew there was a fire to that area. Thanks for the great info.