Father Frederic Baraga was not the first missionary to work in Michigan, nor was he the most popular among his day’s Catholic leaders. Nevertheless, the Native Americans, Fur Traders, and Early settlers in the Northwest Territory of Michigan felt his efforts during the frontier period. He stood up for the Indian nations asking only fairness and understanding. He taught the Indians the Catholic doctrine and prayer for faith in their language and lived a life of service and poverty. When Baraga’s life and work are reflected upon, it appears clear that he profoundly affected the Indians and this state.

Table of contents

- Listen to this Post

- Baraga’s Early Years

- Baraga’s Conservatism and the Church

- Baraga’s Work Among the Native Americans

- The Legend of the Snowshoe Priest

- Book of Prayer in Native Odawa Language

- A Clash of Missions in the U.P.

- Treaty Concerns for Baraga

- A Priest On the Edge of the Frontier

- The Jesuits Built Baraga’s Success

- Baraga Continues to Grow the Faithful in North Michigan

- Frederic Baraga Elevated to Bishop

- Baraga’s Success and Shortcomings

- Baraga’s Path to Sainthood

- Endnotes

- Bibliographical Entries

- Related Reading of Bishop Frederic Baraga

Listen to this Post

Baraga’s Early Years

Frederic Baraga was born in Neudegg, Austria, on June 29, 1797. 1 It was a time of great unrest with Napoleon raging through Europe in the conquest of an empire. 2 Frederic’s family were once wealthy landowners. But the wars between Austria and France put them in debt. The Baraga family sent Frederic to Ljubljana to study under a tutor since the conflict caused many schools to close. Here he studied and became proficient in six languages. 3 When Frederic was fifteen, his parents died, leaving him under the care of his godfather, Dr. Goerge Dolinar, Professor of Church History and Canon Law at Laibach’s seminary. 4 When he was nineteen, he went to the University of Vienna to study law. 5

He was at the university that he decided to enter the priesthood. Baraga went to seminary, and he was ordained on September 21, 1823. 6 He was assigned to the famous parish of St. Martins in Slovenia’s diocese. 7 Catholics at St. Martins were taught to promote Jansenism. Jansenists’ doctrines expressed the philosophy of predestination. Jansenists put a “ban on pilgrimages, sodalities, processions, and novenas; recitation of the Rosary and prayers to the saints were also discouraged.” 8 Consequently, many people avoided the church and expressed disfavor to those seeking a vocation in the priesthood. 9 It was here that Father Baraga started his first fight for the people under his direction.

Baraga’s Conservatism and the Church

Baraga first encouraged the people to return to the sacraments and go to confession. He started to promote Solidarity, a devotional and charitable lay association. 10 The dean of the diocese charged the assistant priest with violating Jansenist principles. He was given a minor reprimand and transferred to an out-of-the-way parish, Metlika. 11

It was here, too, that he tried to shake down Jansenism; however, “he was hampered by the actions of his associates.”12 Father Baraga thought of missionary work after he was impeded at St. Martins, and fortunately, there was a call for a missionary to go to North America. This venture would be funded by the Leopoldine Foundation, named after the daughter of Francis I, Emperor of Austria. This was his chance to do real work without hindrance. 13 In October 1830, he left Metlika and was on his way to North America to meet Edward Fenwick, first Bishop of Cincinnati. 14 His first mission was at Arbre Croche (Harbor Springs). Here he would have a mission among the Ottawa Indians. 15

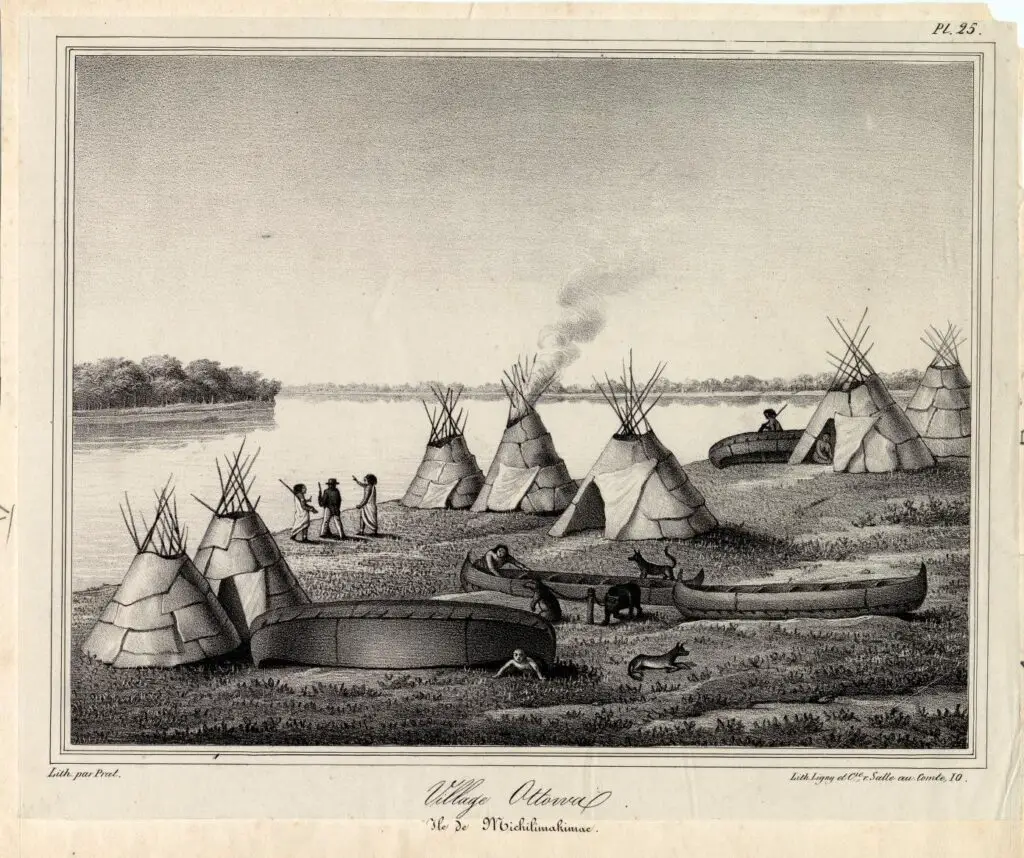

Baraga’s Work Among the Native Americans

The former missionary, Father DeJean, had baptized most of the Indians. It was Baraga’s wish to Christianize the entire village. 16 Baraga started to learn the Ottawa language. It was not easy, so, until he mastered it, he was assisted by Chief Assignak. Assignak was a well-educated man and passed some aspects of the Catholic faith to his tribe. 17 The chief acted as interpreter in the confessional, and due to the extreme respect the tribe had for their leader, the Indians did not object.

Baraga writes of the Ottawa at an early point, “the inhabitants of this part of the country are real heathens and idolaters.” However, the priest found the childlike Indian’s conversion was not difficult once the Indian understood the meaning of the Catholic faith.18 Baraga reopened a school at Arbre Croche, and forty” pupils were instructed by himself and a mixed-race woman from Mackinac. 19 By the end of the year, Baraga also baptized 131 Indians. 20

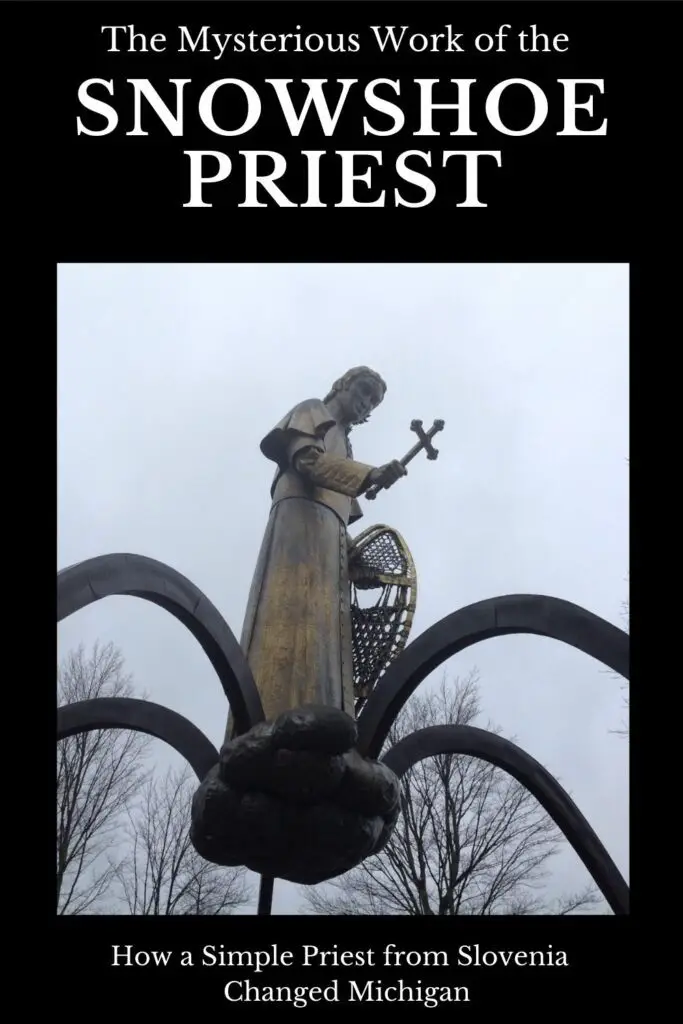

The Legend of the Snowshoe Priest

Baraga also traveled around Arbre Croche to teach and baptize anyone who wanted his service. He walked several miles north to a small village called 0ld Arbre Croche to hold services in a birch bark chapel named after Saint Paul. 21 Baraga was to do many of these short and long excursions around his central mission for the rest of his life. Even as a bishop in his later years, he would travel a hundred miles in snowshoes to help someone who needed spiritual help.

One of Baraga’s biggest fights was against the fur traders. A fur trader could barter Indians out of their furs that they had spent all winter trapping for, for practically nothing. Leaving the uneducated and childlike Indian with shiny trinkets and diluted whiskey. 22

Book of Prayer in Native Odawa Language

Baraga’s major accomplishment was printing a prayer book that was published entirely in the Ottawa language. He went to Detroit during the winter of 1832 to have it copied. During this time, there was a cholera epidemic that claimed many, including Father Gabriel Richard. Here Baraga delivered his eulogy, then went back to Arbre Croche with one thousand prayer books and two teachers.” 23

Bishop Fenwick also died of cholera during the winter, and Father Rese, Vicar General, temporarily filled his seat. Baraga wrote Rese and expressed interest in moving his mission to La Pointe, a small island on Lake Superior’s western end. 24

The Indians of Arbre Croche were almost wholly converted. Baraga felt he would be of better use to the Ojibway of the north. 25 This wish was not to be granted. Father Rese thought that the conditions near the Grand River warranted a mission there first. 26 Many Indians and French Catholics were at the Grand River and needed the service of a priest. Many Christians would be coming from the north, and pagans would be in contact with Baraga. Conversion possibilities would present themselves. 27

A Clash of Missions in the U.P.

Grand River presented itself with a problem that Baraga was not aware of. A Protestant mission had been started nine years previously, and in that time, the minister converted ten Indians. 28 This small group was bitterly opposed to a Catholic mission at Grand River. 29 However, the number of Indians wishing to embrace Catholicism outnumbered the Protestants. The mission was built on the Indian side of the river, opposite a French settlement. 30 Baraga also had problems with fur traders. The French fur traders did not like the missionaries, and Baraga did not like the traders’ unfair practices and the liquor traffic.

Once during Baraga’s stay at Grand River, Baraga’s life was threatened by a band of drunken Indians given whiskey by the traders. 31 “Drunkenness and corruption boiled in the villages, and those who were recently converted found it difficult to believe that only a short time before this had been a part of their lives. They calmly accepted the fact that conversion also put their lives in danger,” 32 Richard R. Elliot of Detroit wrote an accounting of whiskey and Indians for the American Catholic, January 1834. He notes that the traders bought raw Ohio whiskey for twenty-five cents a gallon, then traded for furs worth much more. At times the whiskey was diluted with water, and red pepper and tobacco were added. This concoction was hence called firewater. Elliot writes that a local Baptist missionary instigated a band of drunken Indians to attack Baraga’s cabin at Grand River. Yet Baraga escaped harm.33

Treaty Concerns for Baraga

The United States Government wanted to buy Indian land around the Grand River, and the Ottawas would not sell. Father Baraga did not want to see the Indians pushed west, so he supported the Indians in the stand against the government. The government pressured Bishop Rese to remove Baraga, thereby eliminating resistance to the idea of the Indians selling their land. 34 Father Viszosky of St. Clair came to Baraga and offered to take charge of Grand River’s mission so Baraga could go to Lake Superior. 35

A Priest On the Edge of the Frontier

At first, it looked as if Baraga would only be on Lake Superior for the summer months, then returning to Arbre Croche to attend to the mission there. He went to Arbre Croche first to examine the conditions. He found the parish faith firm and wrote to Bishop Rese expressing this. 36 He traveled to Mackinac then to Sault Ste, Marie, to find a passage to Madeline island and the village of La Pointe on the western end of Lake Superior. He took a small trader’s vessel, and eighteen days later, on July 27, 1835, he arrived at La Pointe. 37 By 1835, La Pointe was a busy fishing village and headquarters of the American Fur Company.

Baraga was the first priest on the island in 164 years. Marquette had been at La Pointe in 1669. 38 La Pointe was a stronghold for the Ojibway in their war against the western Sioux. The American Fur Company came to La Pointe to set up a post in this centralized spot among the fur traders. 39

Many of the inhabitants of La Pointe were mixed-race and worked for the American Fur Company. 40 The language that was spoken, besides Obijway and English, was French. This language was brought to the area by fur traders and Jesuit missionaries many years before. 41 Within a week, a small church was built at La Pointe. This was the first church ever on this island. The Protestants had been here many years, yet never made one. Again, Protestants complained and asked the government not to allow the Catholics to set up a mission. Baraga was allowed to continue with a little argument. 42 The missionary’s first trip outside La Pointe was ninety miles southwest to Fond du Lac. This journey would take three days by canoe. There he met with a pious fur trader named Pierre Cotte. Cotte had instructed many Indians on the ways of Catholic teachings. 43 Here, too, the Indians were ready and willing to be baptized. Baraga writes, “A considerable number of Pagans have already been received into the bosom of the church, namely, one hundred and forty-eight.” The priest continued to teach and baptize in the area for about one month as the harsh north Michigan winter approached.

Baraga still had not received many supplies for his new mission, including winter clothes.44 Yet that did not stop him from continuing his mission that winter with the poor Indians.

The Jesuits Built Baraga’s Success

It is interesting to note why the Indians were ready to embrace the Catholic faith rather than Protestantism. The Jesuit missionaries had some through the Lake Superior area in the 1600s and worked hard with the Indians. Stories passed down through the generations told of these Jesuit “Black robes.” 45 The other factor on the success of Baraga’s missions was that he was French. The French fur traders had little interest in Indian land. The French treated the Indians like a brother, and many fur trading areas were mixed-race. To be sure, this was a sign of the closeness of the Ojibway and French. A factor that was sure to affect the French missionary’s success was the priest’s willingness to learn the Indian language. It was easier to have one priest to learn Ojibwa than for a whole tribe to learn French.

The last aspect that added to the success of Baraga’s mission was that he worked alone. He had no family to worry about in surviving in the harsh country of Michigan.

Baraga Continues to Grow the Faithful in North Michigan

Baraga had been at La Pointe for about two years when a new church was built. Three more churches were rebuilt to accommodate a growing number of converts and parishioners in five years. 46 By 1843, Baraga had heard of the need for a missionary to the east, at L’Anse. After ten years at La Pointe, he went to the copper mining area of Michigan’s Keweenaw Peninsula to start anew. 47

L’Anse was probably the most demanding mission that Baraga was to secure. Indian problems and Methodist pressure to get out of L’Anse made for sharp differences in the early days of Baraga’s mission there. 48 With time, the Methodist mission changed clerical hands, and Baraga developed a deep friendship with the Methodist minister, John Pitizel. As a result, both tasks flourished with time. Baraga used L’Anse as a base mission while taking care of the missionary posts of Grand Portage, Fond du Lac, and La Pointe. Also at Ontonagon and the newly formed copper ore mines of the Keweenaw. 49 During his time at L’Anse, he completed a revised edition of an Ojibway prayer book he had printed in Detroit while traveling with Bishop Lefevere. 50

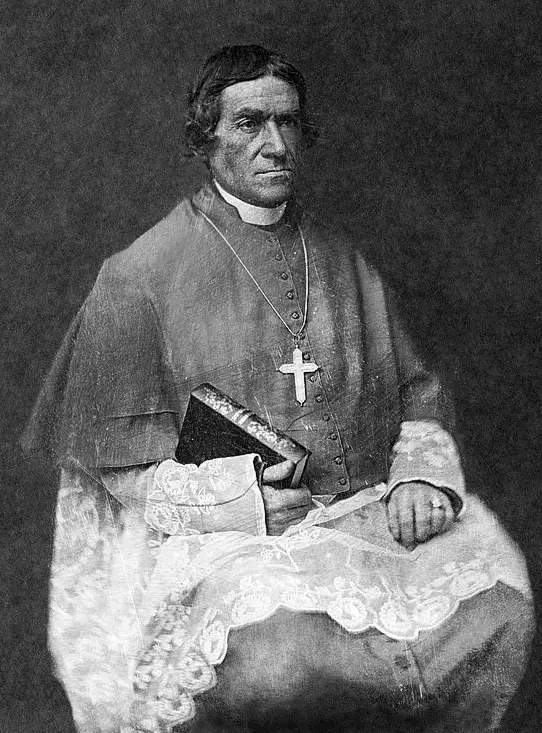

Frederic Baraga Elevated to Bishop

Baraga had been at L’Anse about ten years before he was consecrated, Bishop of Amyzonia and Vicar Apostolic of Upper Michigan on November 1, 1853. 51 From here, he went to Europe to find funds and clergy for the Lake Superior country.

While Baraga was in Europe, he went to the Leopoldine Society for funds. This was to help perpetuate and organize his yet unorganized diocese. He also went and received gifts from the rulers of Austria and Bavaria. 52 Other than raising money, he also needed priests to help him run the missionary posts that stretched from Traverse Bay up and around the Upper Peninsula coasts to the tiny fur trading outpost Grand Portage on the western side of Lake Superior. 53 He went to St. Sulpice in Paris to find future missionaries. He needed ten but found only five. Soon he was on his way back to North America and Sault Ste. Marie. 54

The Sault was his choice of the episcopal because of Lake Superior’s centralized communication point and the lower lakes. Baraga continued his journeys up and down the coast of Lake Superior, baptizing and confirming. 55 It was during Baraga’s early years as Bishop that so much work needed to be done in his extensive diocese. The Jesuits attended to the Sault, and the priests from Europe began to trickle in. Baraga assigned each to a post where they were needed. 56

Father Baraga was about sixty when he was the bishop, yet he still traveled in snowshoes when the need arose. Baraga was becoming exhausted with his missionary life, yet a problem occurred. The copper boom produced an unexpected jump in the western Upper Peninsula population, which meant that the church would respond to the growing area.

The cities of Ontonagon, Houghton, Hancock, Calumet and the rest of the Keweenaw Peninsula created a metropolis of sorts. 57 It has been said that the area of Houghton became the largest city west of New York. At one time during this period, Michigan considered locating its capital at Houghton-Hancock. 58 Yet, during this time, the area had only one or two priests. Baraga would have instead stayed out of the Ontonagon area, but he placed Martin Fox at the St, Patrick’s church. Fox turned out to be a failure, and Baraga continued to have problems with the area. 59

Baraga administered the diocese well until he was seventy, going to the upper Michigan country’s highest reaches until he could walk no more. He died in 1868 at the age of seventy-one.

Baraga’s Success and Shortcomings

Baraga’s mission was a success even though he thought otherwise at times. He taught and protected the original ten inhabitants, the Indians, and found that he wanted almost to become one of them. He baptized thousands and set up and built many churches. He tried to work within government laws to keep the Indians in their native land, even among the white man. His most impoverished and most desolate mission, L’Anse, became his most favorite. He proved that he could go in and help even the steadfast pagan, even where other missions had tried and failed. Baraga did all this and more.

There were also areas that he lacked strength. He did not use his potential political pull as a successful missionary to get what he needed in the Lake Superior country. He had a constant battle in finding priests, getting government help, and fending off Protestant pressure. He also diluted himself to serve as many potential converts as he could find rather than managing several stable missionary posts. Finally, he paid more attention to the Indian problems than the new copper miner settlements after 1840. All in all, the good aspects far outweigh the bad, and his works gained the public mind’s respect.

Baraga’s Path to Sainthood

In May of 2012 Bishop Frederic Baraga was declared Venerable by Pope Benedict XVI. This bestows the title of Venerable Bishop Baraga. The application for sainthood of the snowshoe priest started in 1952. The movement is in its beautification stage. So far, one miracle has been attributed to the intercession of Baraga. An achievement of another miracle will hopefully result in canonization as a Saint.

Books About Bishop Frederic Baraga at Amazon

Endnotes

1. P. Chrysostomus Verwyst, OFM., Life, and Labors of Frederic Baraga, (Milwaukee, Wisconsin: M.H. Wiltzius & Co., 1900), p. 77.

2. Bernard J. Lambert, Shepherd of the Wilderness, (Hancock, Michigan: The Book Concern, 1967), p.3.

3. Ibid., p.14.

4. Verwyst, Life and Labors of Rt. Rev. Frederic Baraga, p. 80.

5. Lambert, Shepherd of the Wilderness, p. 14.

6. Verwyst, Life and Labors of Rt. Rev. Frederic Baraga, p. 86.

7. Ibid., p. 87.

8. Lambert, Shepherd of the Wilderness, p. 27.

9. Ibid.

10. Webster’s Dictionary, Rev. Ed. (1981), S.V. “Sodality.”

11. Lambert, Shepherd of the Wilderness, p.37.

12. Ibid., p.44.

13. Ibid., p.46.

14. Ibid., p.55.

15. Verwyst, Life and Labors of Rt. Rev. Frederic Baraga, p. 109.

16. Lambert, Shepherd of the Wilderness, p.61.

17. Ibid., p.62.

18. Verwyst, Life and Labors of Rt Rev. Frederic Baraga, p. 116.

19. Lambert, Shepherd of the Wilderness, p. 62.

20. Verwyst, Life and Labors of Rt. Rev. Frederic Baraga, p.118.

21. Ibid., p.64.

22. Lambert, Shepherd of the Wilderness, p.67.

23. Ibid., p.75.

24. Ibid., p.76.

25. Ibid., p.113.

26. Ibid., p.86.

27. Ibid.

28. Verwyst, Life and Labors of Rt. Rev. Frederic Baraga, p.143.

29. Ibid., p.148.

30. Ibid.

31. Lambert, Shepherd of the Wilderness, p.100.

32. Ibid., p.99.

33. Verwyst, Life and Labors of Rt. Rev. Frederic Baraga, p.157.

34. Lambert, Shepherd of the Wilderness, p.117.

35. Ibid., p.113.

36. Ibid., p.115.

37. Verwyst, Life and Labors of Rt. Rev. Frederic Baraga, p.172.

38. James K. Jamison, By Cross and Anchor, (Ann Arbor: Edwards Brothers, 1965), p.30

39. Ibid., p.32.

40. Ibid., p.49.

41. Ibid., p.28.

42. Lambert, Shepherd of the Wilderness, p.117.

43. Ibid., p.120.

44. Verwyst, Life and Labors of Rt. Rev. Frederic Baraga, p.179.

45. Lambert, Shepherd of the Wilderness, p.121.

46. Ibid., p.149.

47. Verwyst, Life and Labors of Rt. Rev. Frederic Baraga, p. 205.

48. Lambert, Shepherd of the Wilderness, p. 153.

49. Ibid., p.194. 50. Ibid.

51. Lambert, Shepherd of the Wilderness, p.205.

52. Jamison, By Cross and Anchor, p.173.

53. Verwyst, Life and Labors of Rt. Rev. Frederic Baraga, p.276.

54. Ibid., p.255.

55. Lambert, Shepherd of the Wilderness, p.217. 56. Ibid., p.219. 57. Jamison, By Cross and Anchor, p.185.

58. During my travels in the Keweenaw, I have heard about the growth in the area.

59. Lambert, Shepherd of the Wilderness, p.187.

Bibliographical Entries

Primary Sources

Verwyst, P. Chrysostomus. Life and Labors of Rt. Rev. Frederic Baraga. Milwaukee, Wisconsin: M.H. Wiltzius & Co., 1900.

Secondary Works

Jamison, James K. By Cross and Anchor. Ann Arbor: Edwards Brothers, 1965.

Lambert, Bernard J. Shepherd of the Wilderness. Hancock, Michigan: The Book Concern, 1967.

Webster’s Dictionary. Rev. ed. (1981), S.V. “Sodality.”

Works Consulted

Cujes, Rudolf. Nind janissidog Saiagiinagog. Antigonish, Nova Scotia: St. Francis Xavier University Press, 1968.

Jacker, Edward. Life and Services of Bishop Frederic Baraga.

The Marquette Weekly Plaindealer, Edition of January 30, 1868.

Backerud, Thomas. “American Fur Company Fishing on Lake Superior, 1835–1841.” MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society.

Michigan Technological University Archives and Copper Country Historical Collections

Related Reading of Bishop Frederic Baraga

- Keweenaw Peninsula Michigan Road Trip Fun

- Explore New Tastes With These Five Michigan Wines

- The Pioneer Sketches of Jacob Parkhurst

- A Fortnight in the Wilderness by Alexis De Tocqueville

- Ora et Labora Michigan – A Little Colony in the Wilderness – Part One