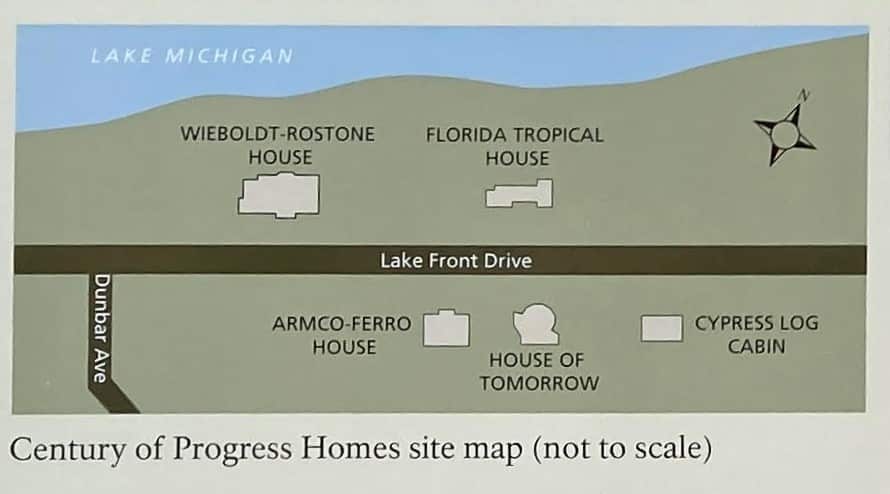

Tucked among the Indiana Dunes National Park on the shores of Lake Michigan is a bit of an anomaly; five model homes from the 1933 Chicago Worlds Fair. They look out of place among the wilds of the park, but they are situated together and offer a commanding view of the lake, and one can see the glimmer of the Chicago skyline to the west.

Each description below was gleaned from the interpretive signs in front of each house. This saves you a drive to the Beverly Shores in northern Indiana.

One of A Kind Houses Salvaged from the Worlds Fair

Robert Bartlett acquired five display homes from the 1933-34 Chicago World’s Fair as a real estate developer. He transported four Century of Progress Homes across Lake Michigan by barge and one by truck to Beverly Shores. Architectural design, experimental materials, and modern technology such as dishwashers and central air conditioning were showcased in these homes. Barlette thought that his five mansions, dubbed the Cyperus Log Cabin, House of Tomorrow, Armco-Ferro, Florida Tropical, and Wieboldt-Rostone, would draw purchasers to his new Beverly Shores resort complex.

Today is the Progress Century. Indiana Dunes National Park Homes are on the National Register of Historic Places. The park leases the homes to Indiana Landmarks. Private individuals are subleasing the houses through this group and returning them to their previous state with private funds. The park and its partners host an annual public tour of the residences.

Story Behind the Century of Progress Homes

The Century of Progress residences featured revolutionary building materials and designs during the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair. Visitors were impressed with contemporary conveniences such as dishwashers and air conditioners. Keep in mind that this was back when enormous swaths of the United States still lacked access to electricity.

Beverly Shores received five Century of Progress houses from developer Robert Bartlett in 1935. The houses are now on the National Register of Historic Places. Indiana Dunes National Park collaborates with the Historic Landmark Foundation of Indiana to preserve and repair the houses through a historic lease arrangement.

The Armco-Ferro House

The Armco-Ferro House, made of corrugated steel panels, was the only Century of Progress Home that satisfied the Fair Committee’s architectural specifications. In addition, it was mass-produced and inexpensive.

The Armco-Ferro House was created by Cleveland, Ohio’s Robert Smith Jr. as a tribute to the qualities of porcelain enamel and steel – represented in the form of a prefabricated dwelling.

This is the only existing Century of Progress home that passed the Exposition Design Committee’s criteria. It could be mass-produced and was affordable to a middle-class American family.

Insulated Steel Inc. built the first house employing frameless steel construction and vitreous enamel exterior sheathing for the American Rolling Mill Company (Armco) and the Ferro Enamel Corporation for $4,500. Ferro’s president, Bob Waver, came up with the notion of employing porcelain and enamel for home building. The 2,400-square-foot building was built in only five days using prefabricated panels.

The frameless home, billed as revolutionary building technology, was made of corrugated steel panels “no thicker than a dime” joined by steel clips. The revolutionary building technology inspired Luston Corporation’s post-World War II prefabricated homes for returning GIs.

The Armco-Ferro house resembled a cardboard box with a shiny porcelain-coated metal exterIronically, this unexpected heat source Fair visitors, most of whom lived in typical bungalows and wood-frame houses from the Victorian era.

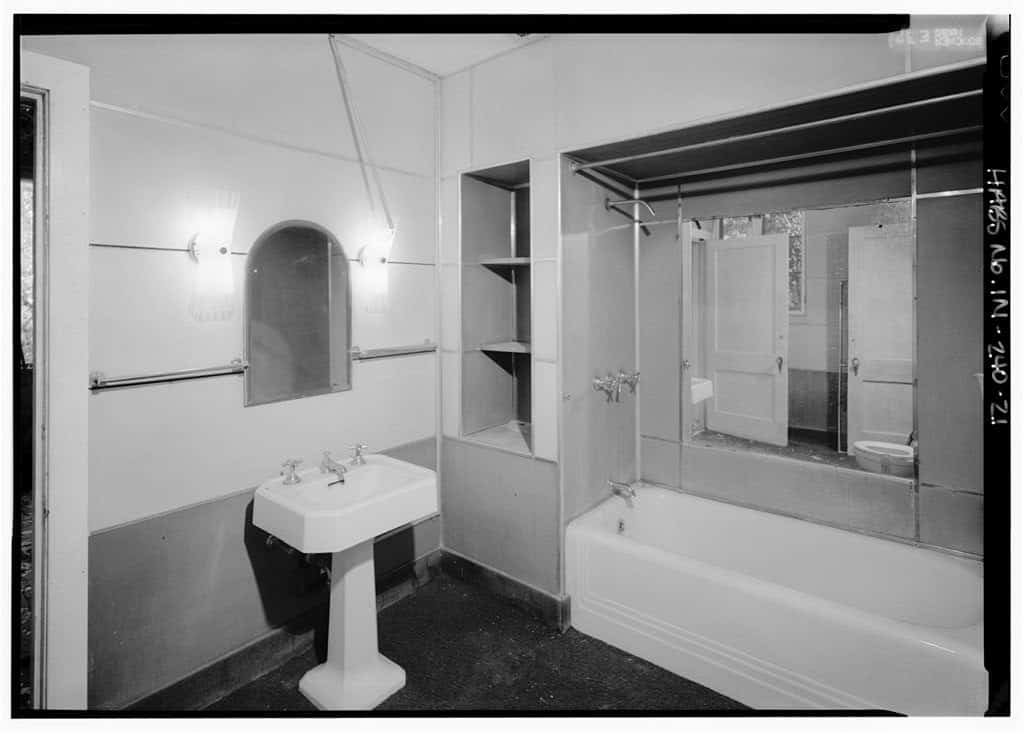

They discovered a lovely house completed with plasterboard, contemporary furnishings, and rooms put out in a familiar layout when visitors entered. With four bedrooms and two bathrooms above and a living room, kitchen, den, and dining room on the ground level, the Armco-Ferro House resembled the typical four-square houses of the period.

The contrast between the modern façade and the classic inside distinguishes the Armco-Ferro House from other Century of Progress residences that pushed the design and quality on both the interior and exterior.

Cypress Log Cabin

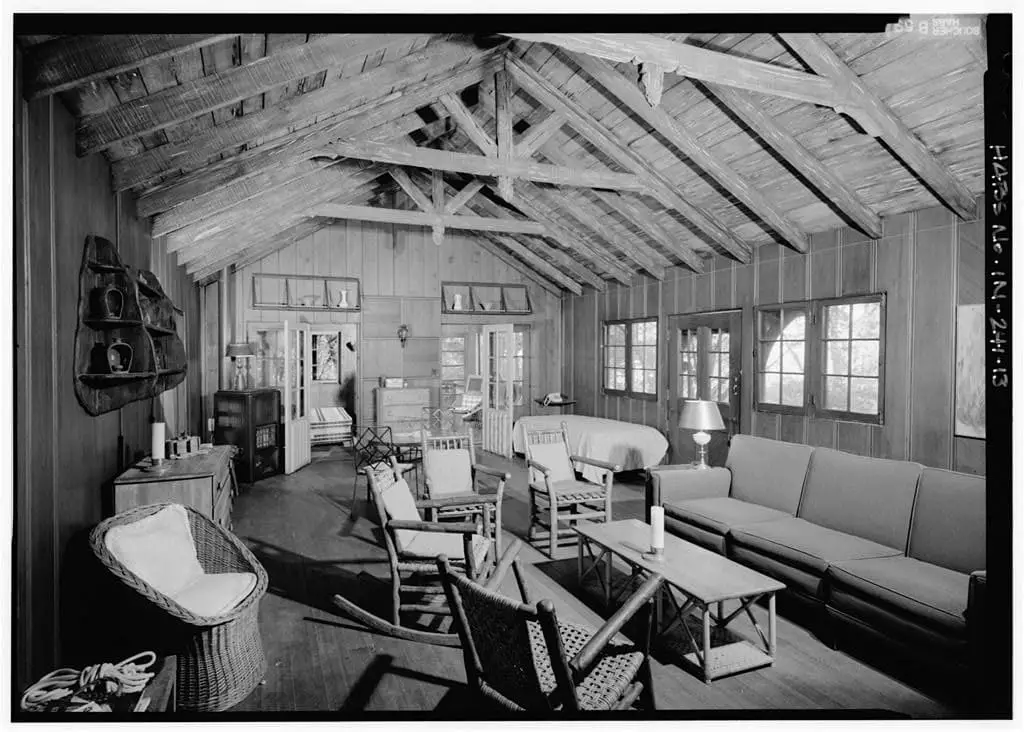

The Cypress Log Cabin’s original rustic characteristics featured carved animal heads and mythical creatures.

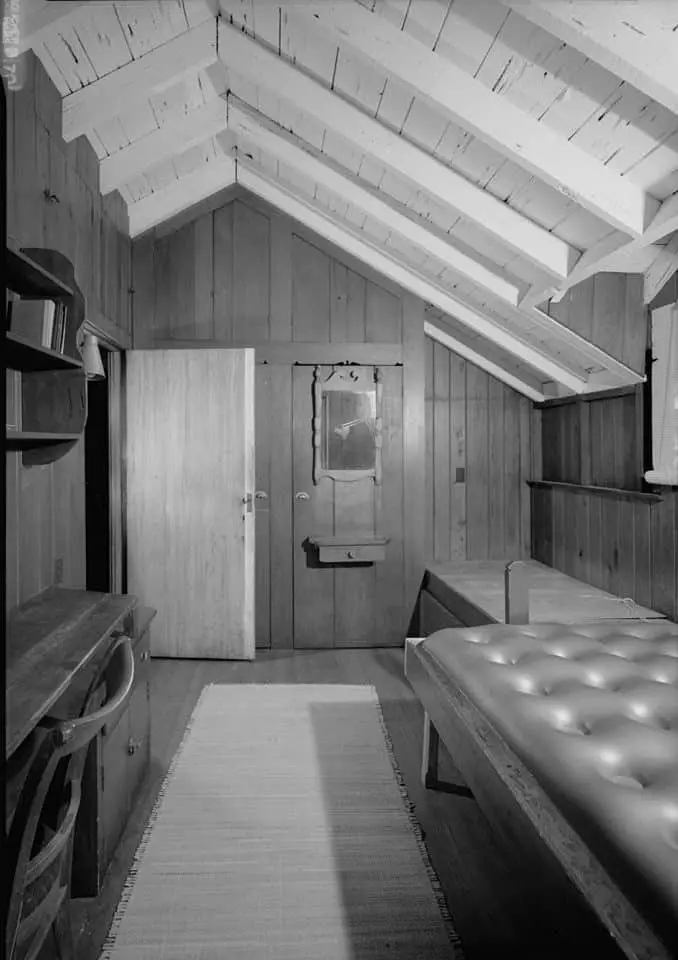

Unlike the ultra-modern dwellings made of steel, stone, and glass for the Century of Progress, the Cypress Log Cabin presented a welcome contrast in material and rustic appearance. The Cypress Log Cabin, sponsored by the Southern Cypress Manufacturers Association, had on display “the many types and applications of cypress.” referred to as “Eternal Wood,” cypress is resistant to water and deterioration. The home, designed by Chicago architect Murray D. Hetherington, showcased the durability and adaptability of wood by using cypress siding, shakes, structural timbers, walls, floors, window shades, and furniture.

The fair’s fanciful exhibit comprised fences, pergolas, and bridges highlighted with decorative cypress knees carved to mimic animal heads and mythical creatures, which captivated visitors’ imaginations. The display educated visitors on all of the great things that could be made from cypress and advocated the usage of the material on behalf of the firms that sold it. Even the garden next to the home worked as a workshop where people could learn how to cut and create objects out of cypress wood.

The main lodge displayed cypress items such as a 150-year-old Seminole Indian canoe, an 1828 confessional grating used in a Catholic church in Louisiana, and a 100,000-year-old piece of cypress discovered beneath a Philadelphia subway. In addition, a second building with overhanging doors was a showcase place for cypress artisans. When transported to Beverly Shores, the structure became known as the Guest House.

Surprisingly, the cabin was the only structure utilized as a residence at the Exposition. Mr. and Mrs. B.R. Ellis of the Southern Cypress Association resided in the ell of the home, which housed the bedroom, hall, pantry, and bath, for both seasons of the Fair.

Wieboldt-Rostone House

The Wieboldt-Rostone home is composed of rostone, a stone-based composite covering. Unfortunately, the material did not endure Lake Michigan’s brutality when visitors entered the winters.

The Wieboldt-Rostone House was created by Walter Scholer, an architect from Lafayette, Indiana, well-known for creating numerous structures on the Purdue University campus. This Century of Progress Home was designed to highlight Rostone, an existing new material advertised as never needing maintenance.

The material is made in Lafayette by Rostone Inc. and is made of limestone, shale, and alkali. It showed such promise as a building material that the company’s creator, David Ross, was hired to build a home for the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair. Rostone, according to the business, could be manufactured in a range of colors and shapes, including slabs and panels to specific measurements.

Most of the design and manufacturing work was done in Rostone and the Indiana Bridge Company facility. Steel beams and columns support the structure, which is clad with precast Rostone panels on the outside. The panels were joined to the steel frame using pre-set fasteners. The Rostone House, weighing 120-130 tons, was the biggest of the structures transferred from the Fair site to Beverly Shores. Massive oak beams temporarily supported the concrete slab flooring during the relocation, and many of them are still in place in the basement. The inside of the residence was furnished by Wieboldt Department Stores in Chicago and Evanston.

The influence of adjacent industries, such as steel mills and refineries, lake-effect snows, showers, and rapid temperature variations, was too much for Rostone. It had deteriorated significantly by 1950 due to environmental and industrial extremes. Perma-stone, a popular concrete, was then applied on the Rostone.

The repaired Rostone panels may be found around the front door, the inner entrance area, and around the living room fireplace. The original designs obtained in the corporate archives shortly before being destroyed were used to reconstruct the Rostone House. There is still a block of Rostone houses in Lafayette with their original exteriors.

The Florida Tropical House

The Florida Tropical House had both indoor and outdoor areas. The Florida Tropical House was a form of an architectural tourism brochure since it was the sole state-sponsored Century of Progress home, commissioned by the State of Florida to entice tourists to “The Sunshine State.” The state even produced a pamphlet advertising the initiative, including an introduction speech from then-Governor David Sholtz.

The “Florida House,” as it was initially named, was the most costly and elegant of the Century of Homes. It was created for wealthy people who enjoyed life in luxury.

Inspired by the tropical atmosphere of southern Florida, a flamingo pink Art Deco villa was created by Robert Law Weed, a prominent Miami architect, to bring the inside and outside together in one space. “The rooms themselves become part of the outdoors,” he added, thanks to the abundance of windows.

The home’s focal point was the two-story living area with an overhanging balcony. The flat top of the structure, modeled like an ocean liner deck, had huge open terraces ideal for sunbathing and lounging. The maritime concept was carried through with portal windows and cruise ship-inspired metal handrails inside.

The house cost $15,000 to build—an incredible sum considering that the average new home in 1933 cost about $5,700. The initial plans called for poured concrete walls, but in order for the house to be quickly dismantled after the Fair, it was framed in wood and covered with a lightweight concrete stucco. Materials local to Florida were employed in the building’s construction, including limestone and travertine, a kind of limestone deposited by mineral springs.

The vivid pink hue of the house has acted as a navigational aid for boats on Lake Michigan throughout the years.

The House of Tomorrow

The House of Tomorrow boasted prefabricated concrete and an airplane hangar adjacent to the garage.

This home, intended as a display of modern architecture and novel construction materials, was a pioneer in developing passive solar heating. This surprised the building’s Chicago architect, George Fred Keck.

Keck observed the workers had removed their winter jackets while working within the glass-enclosed room on a frigid morning during construction. Keck hypothesized that the sunlight flowing through the glass walls might be a low-cost heating source. Following the show, Keck began incorporating south-facing windows and other forms of passive heating into his designs. Ironically, this unexpected heat source played directly against the House of Tomorrow’s most significant advertised feature at the Fair, air conditioning.

At a period when popular new house types included bungalows, Arts and Crafts, and Craftsmen, amenities like floor-to-ceiling windows, open floor plans, air conditioning, passive solar heating, and even automated dishwashers have made their way into the majority of modern homes. Time will tell if the airplane hangar nestled onto the first floor of the House of Tomorrow will also become commonplace.

Discover more from Thumbwind

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

This topic is very interesting, but thumbwind sure needs an editor! I still don’t know if the real estate developer was named Bartlet or Barrette.

The world may never know.