This is the first episode of a new story, the sketches of Jacob Parkhurst by himself. This story was written by my great, great, great, great grandfather, Jacob Parkhurst. It was typewritten and found in a file of genealogical materials passed down from my great aunt. It turns out that this autobiographical sketch has been reprinted many times, but not been published freely on the web or as a podcast.

This story starts before the United States declared independence from Great Britain. Jacob was 12 years old and living in a stockade fort In Hampshire County, West Virginia. The story winds its way with Jacob’s travels up and down the frontier along the Ohio River. So sit back, relax, and enjoy this week’s tale from the end-of-the-road.

Sketches of Jacob Parkhurst by Himself

Sketches of this life and adventures of Jacob Parkhurst; written with his own hand when about threescore and ten years of age, not for speculation or honor, but for the benefit of the rising generation, particularly of his own descendants. Adding a few facts to the many recorded instances of the sufferings of the early pioneers along the Ohio River.

This book was originally published in 1842, reproduced in 1893 verbatim et literatim by

Mort Edwards, in Knightstown, Indiana.

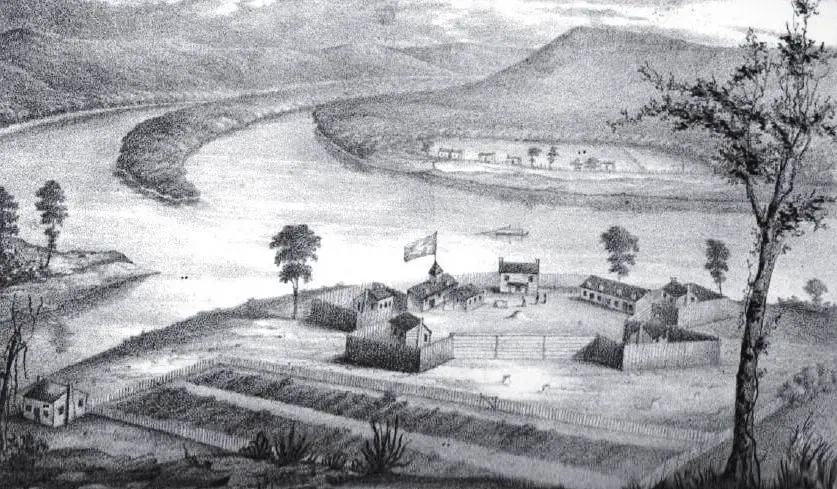

My parents emigrated from the State of New Jersey to Virginia, in the year 1771, where my father raised a crop, and where I and my twin brother Isaac, were born, on the 19th of February, 1772. About the year 1773, we moved to Pennsylvania, in Washington county, where we lived through the Revolutionary War, exposed to the tomahawk of the merciless Savage; suffering all the hardships of a wilderness country, and the privations of a calamitous war. The first summer we forted was the summer of 1774, when we moved about 12 miles to Enochs’ fort, where we lived, and remained all summer, having left our little residence of a log cabin, and a few acres partially cleared in the dense forest.

Being much alarmed by the tidings of the Indians had crossed the Ohio River, and steering towards our frontier, of which we were about in the front. The men of the fort, as many as had rifles, armed themselves as well as they could, though ammunition was hard to obtain, and joined into a working party, and went round in turn to each one’s field, and some stood guard, while the balance planted, or hoed their crops. Thus with much difficulty, they obtained a very small pittance of provision for the wants of their families, but our little band was favored with no loss of lives from the enemy.

In the fall when hunting time came on, the Indians withdrew, and we moved home, where we lived independent, for my father had been on a trip to Laurel Hill, bought a pair of hand millstones, and packed them out on the old bay mare, and we could grind our own corn, and make our own Johnnycake.

I have started a few things by information, which happened before my earliest notice. I will now try to state a few facts of my own recollection. On April 15th, 1775, my father went some 10 or 12 miles and brought an old Dutch woman, whom they called Granny French, my aunt Huntington was also there, and one or two other women of the neighborhood, but my oldest brother, took his little wooden wagon which he had built for his own accommodation, and loaded on the two twin boys, and went about a mile to the nearest neighbor, where we stayed till towards night. When we came back, my oldest sister informed me that we had a younger brother and that I was not the youngest son, (for so my mother called me.) But I went near to the door of the cabin, where I peeped through the crack of the wall. My mother, seeing my eyes shine through the wall, said to me, ah Jacob, you are not my youngest son now. With that, I dodged back and hid behind the oven, and would not go in till night.

About these times the hunters used to come to my father, as we were in the front range. We had an old dog that used to catch their wounded deer. One day he chased an old buck into the creek, and my oldest brother took his tomahawk and ran down, and when the dog caught the buck by the nose and held him, he waded in and pecked away, the dog holding his grip, till the buck sunk down in the water. My brother was a lad of about thirteen years of age.

About this time, our living was venison and hominy, with some mush and milk, and some corn cakes, ground on a handmill and sifted through a splinter sieve. Our common dress was tow linen or dressed deerskin when we had clothes. But being boys, such as I and my twin brother, till about eight or ten years of age, had to do with one long shirt a year, which came down to the calf of the legs, and when they were worn out, we had to go naked, or nearly so, till the next crop of flax was manufactured into linen, which was done in the winter, for in the summer we had to live in the fort, and if we could manage to raise a little corn and potatoes, we felt very thankful for the supply for the winter.

About in this manner we passed on, forting in the summer, and staying at home in the winter, till the winter that I was eight years old, which was 1780, which was called the hard winter, the snow fell early, more than two feet deep, but we had not our new shirts yet, therefore the twin boys were nearly naked, but I began to contrive for myself, accordingly. I found a small deerskin that had been killed out of season, too thin to dress, so I put strings to it, and turned the hair side next to my belly, and wore it as an apron, then I was well prepared to face the winter winds, my feet and legs being still naked, and my old shirt all gone except the collar and a few threads hanging around. It was not long until we got our new shirts, which came down to the calf of our legs, then we were well clad for the winter. Though we had no other clothes, we were too warm to stay in the house, especially by the fire.

So we got corn stock guns, and would go a-hunting to the creek, twenty or twenty-five rods from the house, where we would pretend to shoot and get the outside bark off of the inner bark for skins, and then return home with our skins, the snow being up to our forks every jump. Sometimes when we did not go hunting, we would get too warm, and go out where the snow was drifted by the fence that joined the house, we would climb up on the fence and jump heels foremost all overhead and ears in the snowbank, and then run to the fire, with legs as red as an old turkey, this was something like case hardening. By this time there were several new forts built, namely, Jackson’s on the South Fork of Ten Mile, and Atkinson’s on the middle fork of Lindsleys, on the same creek, to which the last-mentioned fort we belonged; but my mother had got very opposed to living in the fort, on account of her children running into all manner of mischief and evil.

In the summer of 1781, about the last of June, the express came that the Indians had crossed Ohio River, and was steering for the frontier; my mother proposed to go to the woods, so we loaded up our beds and bedding which were but light and moved into the woods about a mile from home and in the head of a lonesome hollow between the two creeks, where we stayed two days and one night, but there came a great rain and wet our bedding, so that we moved home again, the enemy having made their way to some other settlement.

We now stayed at home till about September, being favored with some Rangers that were sent from the interior parts. One of these spies who camped at our house was by the name of Caleb Goble, he and my brother Daniel took a scout onto the head of Wheeling and down to the fork, where they spied a trail, of Indians, about five which had gone up the other fork, which was called Templeton’s Fork. Our spies hastened home with all possible speed to give the alarm. So we loaded up on horseback, and started, not to the fort, but to a friend, who lived 8 or 9 miles in the interior; but we had not gone far till we heard the news of the murder of two young men of the name of Carrol, that lived towards the head of the creek on which the tracks were seen by the spies, which was about two miles from our house. The Indians lay in ambush some distance from the house. About daylight as the young men went out to gather some wood for the fire, the Indians shot them both, which alarmed the women and children in the house, and while they were scalping the two boys, the family made their escape into the cornfield and through it into the woods, and so gained their retreat to the fort; but before they got out of the cornfield, they heard them shoot the old bitch at the door, who was not for letting them in, but when they had dispatched her, they entered the house and ripped open the beds, and threw the feathers all over the house and carried off what they would clothing.

In April 1782 about two miles from our house, a young man by the name of Stephen Carter, went out to hunt turkeys. Before it was light, he thought he heard turkeys gobbling, but the nearer he approached, the more he suspected the fraud, till at length he discovered five Indians secreted in order to decoy the unsuspecting, he ran back to the house, alarmed the family, who escaped to the fort, which was one mile distant. He then alarmed the neighborhood. The news came to our house very early, we packed up in short order, and started for the fort.

The Indians, finding they were discovered, left the creek they were on, and crossed the high hill, and struck the head of the run that we were encamped on, the summer before, and went down the run, till they came in sight of the road, just as we got along coming around the point of the hill, there were three men with us, or rather as a flank guard who had crossed the point on our left, and discovered the Indians up the run in gunshot, and one of the men raised his gun to shoot an Indian, another advised him not to fire, lest the horses should frighten, and throw the women and children; but the word was given that the Indians were in sight, when the leader of the packhorse company, whose name was Benjamin Goble, called out with a commanding voice, come on!, for here is the Indians.

The Indians supposing there was a troop of men behind, fled across the hill to the creek, that we had come down, while the force behind, was three families of women and children, several boys of us on foot, who scampered up the hill, for we had a long hill to cross to the fort. We got to the top of the hill, and the road made a circle round the head of a hollow, when I took a course straight across, but got bewildered, and kept down the branch till I came to the forks of the creek, one mile below the fort. I then turned up the other, and came to the fort before I was missed; but neither my mother, my father, or my oldest brother were along with us, for the two latter had gone the day before, a distance of 10 or 11 miles, to get some fruit trees to plant out, and my mother said that she would stay at home and keep the old gun, for fear the men might come by the road so that they could not hear the alarm, and thus be taken by the enemy.

As soon, however, as it was known in the Fort, that my mother was not in the company, and that she had stayed at home, and that the Indians were steering in that direction, an elderly man by the name of Caleb Lindlay, jumped on his old roan horse, and said that he would bring the old lady into the fort, and put out with all speed until he got to into the bottom, within a hundred rods of the house, when he discovered the Indians raised the yell, after him. The old man also yelled, but the Indians halted. The old man then turned his horse again and called for Captain Rice to come on; we’ll have their scalps immediately, at which the Indians wheeled, and ran across the bottom towards the big hill, and the old man rode up to the barns and called for the old woman, who at hearing the yelling, went into the loft with her gun, and pulled up the ladder, but when she heard the call at the barns, she did not know whether it was friend or foe, but when he remarked that he was afraid they had got her, she then came down with the old rifle gun which she had kept close to her all the time of the noise.

The old man took her on behind him and carried her to the fort. By this time, the men of the fort were in the greatest anxiety, and started about a dozen ran to pursue the Indians, but they could not overtake them. About four months after this, my brother Thomas was born in the Fort. I think this was the last summer that we lived in the Fort.

As the emigration extended slowly to the west, the Indians, therefore, committed their murders along Wheeling creek, or along the Ohio River, and the inhabitants would frequently run together at our house, or some other suitable place of defense, till the Indians had re-crossed Ohio. In one of those excursions, they came stealthily, early in the morning, to the house of one Davis, who lived near. Wheeling about 12 miles from our house, and murdered and scalped the whole family except one son and one daughter. The son was out hunting the horses and came home while they were in the act, but made his escape. The daughter found her way into the cornfield and made good her retreat.

Another family by the name of Crow, a Dutchman, had two daughters and one son killed on Wheeling, with whom I was acquainted, and another son shot through the ear, whom the Indians chased to the high bank of the creek, where he jumped down into a deep hole of water, and swam out and escaped, their guns not being loaded. Another man, named Timothy Bean, with whom I was well acquainted, lived in Wheeling, about 12 miles from our house, his wife not being with him. Three children, two girls, and one boy were out in the bottom, with their father, gathering walnuts, when the Indians came rushing on them with their tomahawks and knocked down all three of the children, but as there were but two Indians, while they were scalping the two girls, the boy got up and ran to his father, who was at work in the field, though the boy was badly hurt with the blow on his head. The Indians hurried off with their two scalps, and having stripped the two girls of most of their clothes, hurried off to cross the river before being overtaken. The old man took the lad on his back and carried him all the way to the ten-mile settlement, but the girls lay with their skulls naked, and their bodies nearly so, the remainder of that day and the night following, and all the next day till in the night. A company of men arrived in order to bury them, under the command of Major Henry Dickerson. But when they had found one of the unfortunate victims, who was dead, they searched around for the other, who had crawled down to the branch for a drink and was lying partly in the water, not being able to get back. She heard the men in the dark, and though they were Indians, and laid still until they drew near her when one of the men spoke to the Major and called him Henry; then she called out, don’t leave me, Henry. They wrapped her in a blanket and carried her to Father Crafts where she lived several days, but her skull had been fractured, and the flies had lodged their eggs in her skull, which grew into large creepers that appeared about the time she died. She said her sister lived through the remainder of the first day, until about midnight. – She thought she heard her groan her last. I think this was about the last murder that was done by the Indians, in the region of our settlements, it is long after peace was settled with Britain.

But the emigration still extended to the west, until our settlement was no longer a frontier. But we had another enemy which infested our new country that was something like the Indians, for they would hide in the grass until they got an opportunity to strike, and then run and hide. They were the rattlesnake and the copperhead. They were very numerous and had their dens in the rocks, where they wintered, and we would go early in the spring and slay them by dozens.

About the year 1786, towards the last of August, I was helping my father to load some rails on a sled, to fence a new wheat field, as we were at work at a large pile of rails, that had been made the winter before, there was a yellow Rattle Snake concealed under the rails, end it struck me in the big vein on the top of my foot, and the blood gushed out and ran down to the bottom of my foot. I saw the snake after it had done the act, but did not kill it for my father hurried me to return home.

So I started and ran home, and left Father to kill the snake, but when he turned his attention to the snake, behold it was gone. It is said that they always hasten to the water when they bite, or it proves fatal to themselves. I felt no distress till I got home and set down, when my nose began to feel numb, my tongue to quiver and feel clumsy, followed with a distressing sickness at the stomach, and pain in the bowels, which lasted till some time in the night, when I became senseless to pain, till, towards the day, I seemed to awake, as out of sleep, and wanted to make water, which appeared to be nearly all blood, my nose had bled abundantly on the pillow, and some places on my hands and foot that were scratched by the briers, the blood started out fresh, and my nose continued bleeding every day, for a week or more and was hard to stop. My leg swelled up to my body and turned the color of the snake. I lay for nearly a week in a doubtful situation.

When I began to mend, it was about three weeks that I could not walk or go out of the house, but in about five weeks, I was so that I ran about tolerably brisk, and became sound and well, and grew more rapidly than before, so that the next winter when I was about fifteen years old, my weight was one hundred and fifty pounds.

In the fall of 1788, my uncle Gershum Gard moved out to Redstone on his way down to Syms’ purchase, or to the North Bend, where they settled – and with him, his sons, and his sons in law, daughters, married and unmarried. One of my cousins by the name of Jemima came to stay at our house all winter, who was an agreeable young lady, whom we all respected.

The next spring being 1789, my uncle pursued his journey down to North Bend. My brother in law also packed up and went with them, leaving his place on Dry Run to be rented. His name was Stephen Carter. My father also went along to view the country and left the boys to manage the farm, till after harvest, for he and Carter tended a crop of corn at the North Bend, where early the next spring, Carter was killed and scalped by the Indians, in sight of the garrison.

In 1790, was a very scarce season in Pennsylvania, the corn crops having failed the summer before, the grain got so scarce before the harvest, that some had to cut the early rye, and dry it over the fire like flax, then rub it out and boil it to preserve life. We had nearly half of a five-acre field used up in this manner. But in August, there was a call made by the government, for 300 men to be taken out of Fayette and Washington counties, to join the Kentucky Militia, to go against the Indians, under General Harmar.

Our militia was mustered, and volunteers were called for, when I, and some other of my comrades, turned out, it is the first muster that ever I was at after I was enrolled, but this was sad news to my poor afflicted mother. My father was at the muster, and I informed them that I wanted to go down to the North Bend, to see what had become of my sister, whose husband the Indians had killed the spring before, which pacified them in some measure.

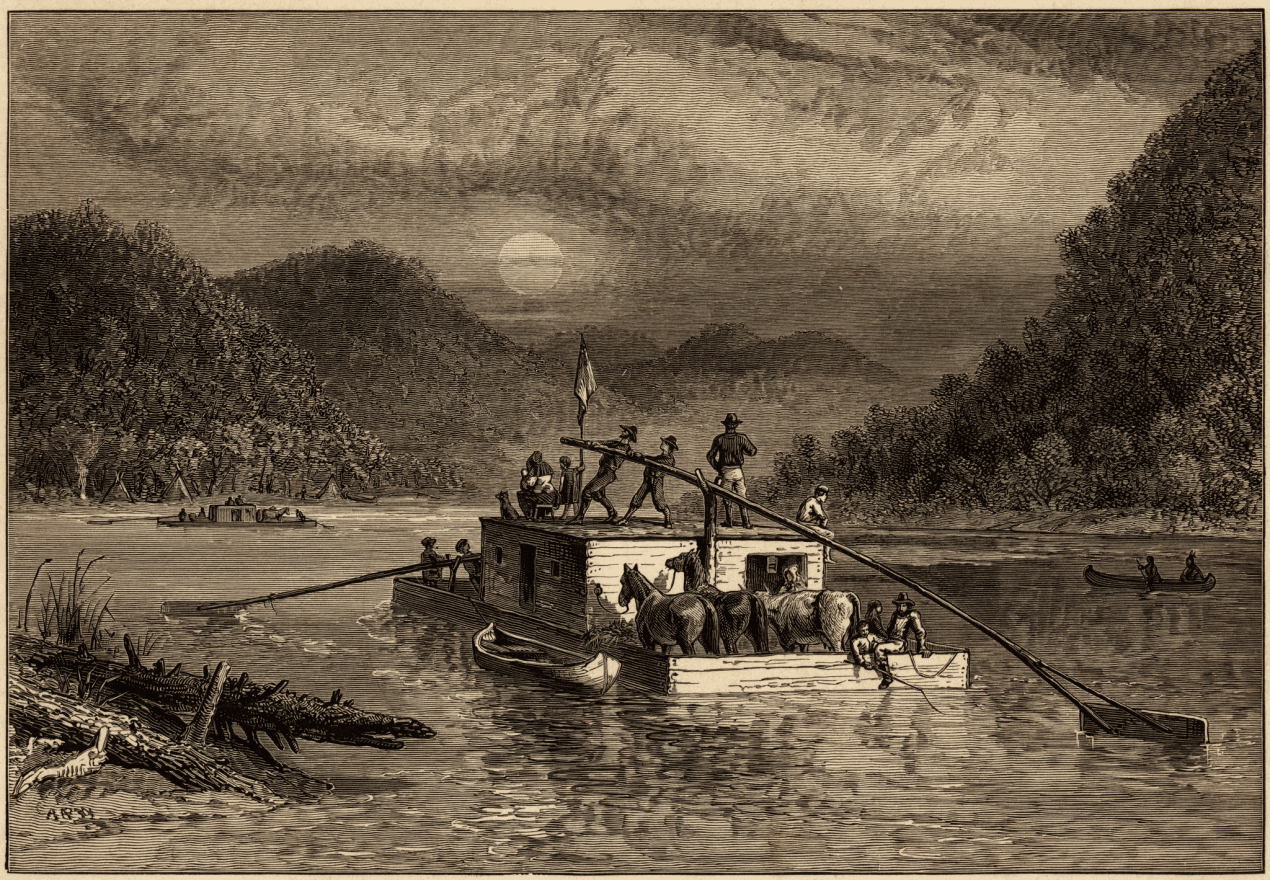

So they fixed me off in the best manner they could. I took my oldest brother’s hunting gun, which was sure-fire, and a sharpshooting rifle. We then met at Washington, where we mustered under Lieutenant Sutton – thence we marched by land to the Ohio River, at McMahan’s bottom, between Wheeling and Grave Creek, where we joined the Fayette militia, who had descended the Monongahela River, by water – we then embarked in nine flat bottom boats, where we thought we suffered many hardships. Being, 300 of us crowded into nine boats with beef cattle, horses, flour barrels, and kegs, so that there was scarcely any chance to lie down, but on the barrels and bags, or under the cattle’s feet. The river is low, our voyage was tedious, but in about eight or nine days, we arrived at the bottom opposite Cincinnati, below the mouth of Licking, which was then a thick forest, covered with beach and buckeye timber.

Here we joined the Kentucky militia and was under the command of General Harmar. We lay there about three weeks, in which time, I got a furlough and went down to the North Bend, with Captain Virgin, who had visited our camp, and took me in his canoe, he was from Pennsylvania, but now lived at the North Bend, and gave me some account of my sister, the widow Carter, before named. So my cousin Aaron Babbitt and myself got into his canoe and went down with him where I found my sister in a log cabin, but no cider. She had just survived a hard siege of the fever, which had left her bald-headed, and hard of hearing.

We stayed a few days and then returned to the camp, where we lived on fresh pork and dodgers, made of damaged meal, and we did not draw salt enough to half-season our pork, which caused dysentery to prevail amongst us, so that I got so weak in a few days, that I was doubtful, that I should not be able to march out to the Indian towns; but as the time drew near, and the day appointed, I concluded to try marching, and see if it would not cure me. So we marched the first evening to Mill Creek, which I found to be hard for me to perform. It rained hard that night, and wet our beds through our tents.

The next morning, finding myself unable to march, I got a pass and returned to the hospital at Cincinnati, where I took a strong dose of Tartar, which worked me severely, and after a few days I got into an old canoe, and went down, to North Bend, to my widowed sister, were I remained. I hunted her cows and killed turkeys until the company returned, and had done but little more to brag of than I had. Then I went up to Cincinnati, to greet my messmates and fellow soldiers, who had survived the returning detachments; where I found a messmate, as well as an old school mate of the name of Jacob Allen, who agreed to go with me to North Bend and stay all winter, and so we went down and agreed to get wood and grind the widow’s corn on the hand mill for our board, and for our meat, we killed the bucks, turkeys and the possums. In this manner, we lived, and had frequent tours of scouting, as we were joined to a company of volunteers under Captain Brice Virgin, and acted as a defense to the garrison at North Bend, and by frequent tours of scouting up the Miami, white water, and during which time we boarded at my sister’s, the widow Carter.

Late in the fall, Allen and I went over into the Miami bottom, where we found a pile of leaves, we went to it and found two deer, a doe and a spike buck, carefully laid together, and buried with leaves, being killed by the Panthers. We skinned them, and carried home the hindquarters, as they were well bled, and yet warm. It was a scarce time of powder and led, but one evening the scouts came in a little before night and commenced shooting at a mark, offhand, for the lead. I was very scarce of bullets, but I concluded that I would risk one anyhow. So I fired away, and buried my bullet in the black, almost cutting the center. The older hunters shot a number of times, but could not draw my shoot. So I cut out my led and carried it home, of which I had a handful, which lasted me through the season.

As the season advanced towards Christmas, the weather was cold, and the ice ran thick in the river, and on Saturday evening before Christmas, about thirteen of us took a notion to take a tour. We crossed the Ohio, notwithstanding the ice ran rapidly – we went down to Tanner’s station, on the Kentucky side, below the mouth of Miami, where we stayed all night in the morning, the ice ran thicker than ever, but we got a small canoe, that would carry about four or five men, and with difficulty, the two first loads got over; but just as the last got about the middle of the river, there came a cake of ice which nearly filled the channel of the river, and we had to drive before it, sometimes drive against other cakes and were nearly overset or thrown out of the water, but we made a shift, by breaking the ice with our paddles, to get to the shore, or where the ice was gorged up so that we drew our canoe upon it, and so got ashore.

We then took a course across the hilly country, towards where Brookville now stands, and camped out in the snow and frost. As there was tracking snow, and cold weather, we killed one deer, which supplied us for meat. The next day we struck White Water, and followed down to where it enters the Miami, which brought night upon us as there were no white inhabitants west of the Miami, we struck fire, but soon found that the trees in the bottom were abounding with turkeys, and the moon was about the full, so we prepared for an evening hunt, for we had no meat for supper, so when the moon got high enough, we went and killed what we wanted.

By getting them between us and the moon, we could draw sight on them, and fetch them down almost every shot. So we dressed and roasted what we needed for supper, and seasoned it high, so when we planted our sentry, we went to our lodging which was a blanket spread down on the leaves, and another over us by the fire. But when we got to bed, we could not sleep. We were so thirsty, so we took an old wool hat that had gone to seed, and turned it inside out to carry water in. So we took it in rotation, for the full of the hat would nearly go round. So we took a nap. In the morning we took the balance of our turkeys and went home.

Soon after this, I took another trip up White Water to hunt a tree to make a Pirogue. We came to a pond or bayou in the bottom where we saw some wild geese; so we snuck up and discovering some very large white ones we both took aim, but his gun missed fire, but I killed a large swan which I skinned and stuffed and had it for a pillow which I stayed at North Bend when I slept by the fire which I commonly did when hunting.

On Christmas day Judge John Cleave Syms invited the whole Garrison of men, hunters and all, to the raising of a fort or blockhouse over the Miami bottom. It was a log cabin with sixteen corners, which he had planned so as to afford a chance to fire on the enemy from the portholes in every direction if they should advance to scale the walls or set fire to the building; we did not finish it that day, for the days were short and it was a troublesome building to raise; it took eight cornermen, each, of whom were required to carry up to two corners. I was one of the cornermen; but we did not cover it that day, and the weather setting in hard, it was not finished when I left North Bend. It was calculated for four fireplaces, and for four families to live. I thought it was an invention of the old Judge, to have something curious and exciting to send back to New Jersey; but I never understood that it was invaded by the enemy, as the settlements soon became consolidated up the Miami to Colerain.

Related Reading

102 Years Ago in Harbor Beach History

American Indian Names of Michigan’s Saginaw Valley and Thumb